What it’s like to visit a North Korea-themed pub as a defector in South Korea

Kim Eun-joo, 37, grew up in the mountains of North Korea’s Hamgyong Province, near the border with China. By North Korean standards, her family was well off, working as currency traders.

But 14 years ago, Kim defected to the South. Now, she lives in the capital, Seoul, and is studying journalism at a local university.

Tonight, Kim is visiting one of the few spots that exemplify the country she left behind. It’s a bar and restaurant called the Pyongyang Pub. Located in the heart of Hongdae, a hip area in western Seoul known for its bustling youth culture, Pyongyang Pub, which blasts old-fashioned, jovial North Korean tunes at its entrance, protrudes like a sharp nail. Young couples and inebriated packs of college students walk past, only to look back and do a double-take, quickly retreating their footsteps to peer inside the real-life anachronism.

Related: North Korea destroys liaison office on border with South

Upon opening in October last year, the pub attracted mostly curious 20-somethings who were entertained by the sheer idea of drinking with friends in a North Korean-themed space where the walls are covered in red banners mimicking North Korean political slogans. One reads: “More alcohol for comrades!”

“This used to be a Japanese izakaya, but I knew people were curious about North Korea. I didn’t know much about it, so I thought a North Korean place might be fun.”

Pub owner Mr. Jang, who did not disclose his full name to protect his identity, has owned a few places in this hipster, barhopping district. He explained the theme: “This used to be a Japanese izakaya, but I knew people were curious about North Korea. I didn’t know much about it, so I thought a North Korean place might be fun.”

But a slew of people, both defectors and South Koreans, took offense after the pub opened.

Related: North Korea stops answering daily calls with South over leaflets

“They thought I had political motives, so they cursed at me,” Jang said. “I’ve never been cursed at like that in my entire life. My goal was just to replicate a North Korean pub as authentically as possible.”

North and South Korea have been geographically divided for more than a half-century. Even in the democracy of South Korea, it’s illegal to praise North Korea or to distribute materials that may be perceived as North Korean propaganda, according to Korea’s National Security Act. That’s why Pyongyang Pub faced so much backlash before it opened.

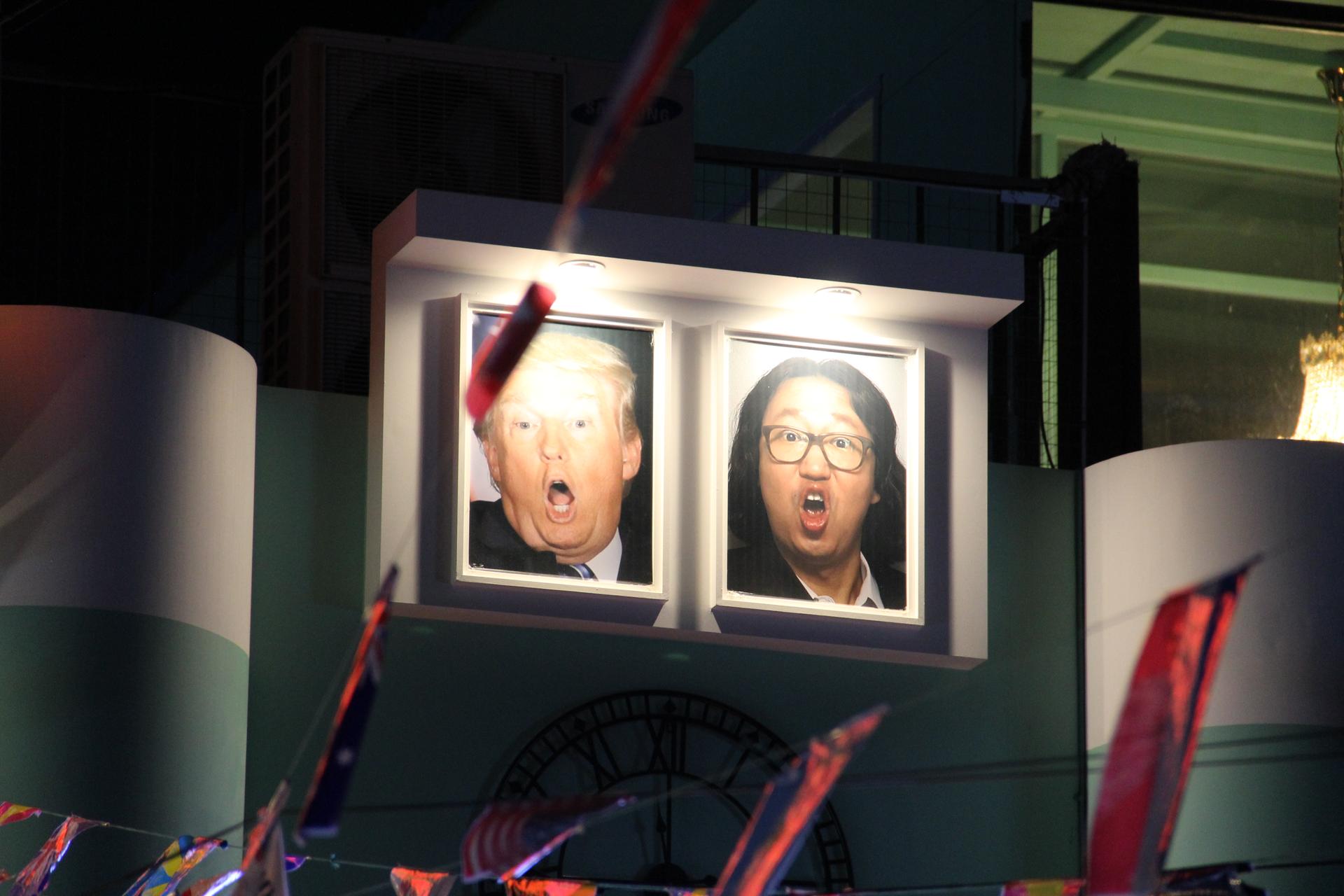

After the pub made some adjustments to its design, including taking down portraits of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il at the entrance, law enforcement ultimately determined that the establishment didn’t violate any laws.

Related: America’s BLM protests find solidarity in South Korea

Inside Pyongyang Pub, soft mint and pink accents reminiscent of the pastel buildings in North Korea contrast with gaudy banners mimicking North Korean propaganda. Tongue-in-cheek quips like “Let’s revolutionize side dishes!” and “More booze to the people!” are written on the restaurant walls, transporting patrons to another time and place.

Kim slightly bobs her shoulders up and down to the familiarity of the songs blasting from the speakers but doesn’t loosen up.

“It feels similar to Pyongyang, but something’s off. It’s not quite the same,” Kim said.

Related: Move over K-pop: Korean youth turn to old-time trot music

The music swaps between hits from the North to K-pop tunes from the South. Kim described the uncanny juxtaposition as jjambbong, a Korean-Chinese spicy seafood noodle soup that’s also used as a metaphor to describe something that’s “a messy jumble of everything.”

The waitress was dressed in a North Korean hanbok, a traditional dress.

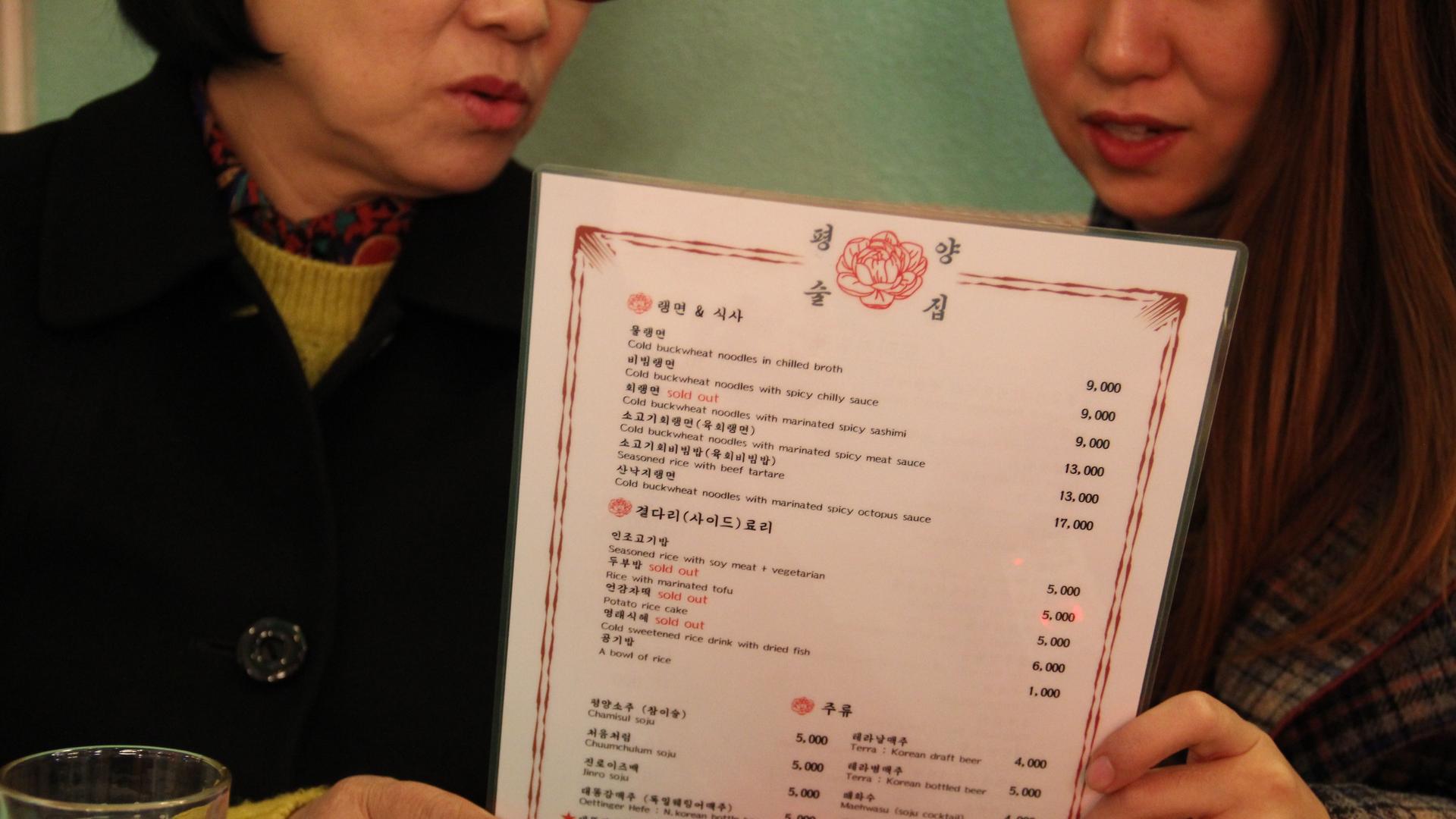

Kim asked the waitress for a recommendation, and she said gopchang jeongol, or beef tripe hot pot — a traditional South Korean dish.

North Korean dishes, the waitress explained, are too bland for customers. Kim nodded, acknowledging that a lot of cuisine in the North is simple: potatoes, corn noodles and minimal seasoning. It’s more about survival than culinary creativity.

When the food arrived, Kim was pleasantly surprised that the cold noodles, mool naengmyun, were served in a wide-rimmed brass goblet, just like in North Korea.

Kim nodded in approval. They definitely did their research, she said. But they can only get so close to the flavors she experienced back home.

“I’ve tried so much delicious food in South Korea, and now, I know what it feels like to be full. In the North, we didn’t have many choices, and we were always hungry. So, even if I eat the same North Korean dish today, I don’t think it can ever taste the same as it did back home.”

“I’ve tried so much delicious food in South Korea, and now, I know what it feels like to be full. In the North, we didn’t have many choices, and we were always hungry. So, even if I eat the same North Korean dish today, I don’t think it can ever taste the same as it did back home.”

Tofu rice, as it sounds, is fried tofu stuffed with rice. The pub served the dish with spicy, seasoned rice inside, but according to Kim, in North Korea, the rice is plain white rice served with a separate spicy paste to go with it.

There’s a North Korean beer called Daedonggang, named after a famous river. But the pub tweaked that too, so the label reads “dae-ddong,” which literally translates into “poop river.”

“I don’t get a great feeling about this. If they just named the beer after Daedonggang river, maybe people might learn that it’s as beautiful as the Han River in South Korea,” Kim said.

Kim said that she doesn’t quite know what to make of spaces like the pub that are filled with elements of home but ironically, deepen her alienation as a North Korean in South Korea.

“When North Koreans first arrive in Korea, they come with full hearts and great expectations. But the reality is much different. People can be very cold. That’s why a lot of defectors end up feeling really let down. Since I arrived here, my emotions are kind of numb.”

“When North Koreans first arrive in Korea, they come with full hearts and great expectations. But the reality is much different. People can be very cold. That’s why a lot of defectors end up feeling really let down,” she said. “Since I arrived here, my emotions are kind of numb.”

Then, she paused.

“You start questioning yourself, and you wonder how much of what you’re feeling is even real.”

Before leaving, Kim asked Jang the pub owner for his card. Even though it’s far from being home for defectors, she told him she’d like to come back and help him make this place a more educational experience for young South Koreans — a space where they can engage with North Korean culture in a meaningful way. Jang nodded, and they agreed to stay in touch.