Meet June Almeida, the Scottish virologist who first identified the coronavirus

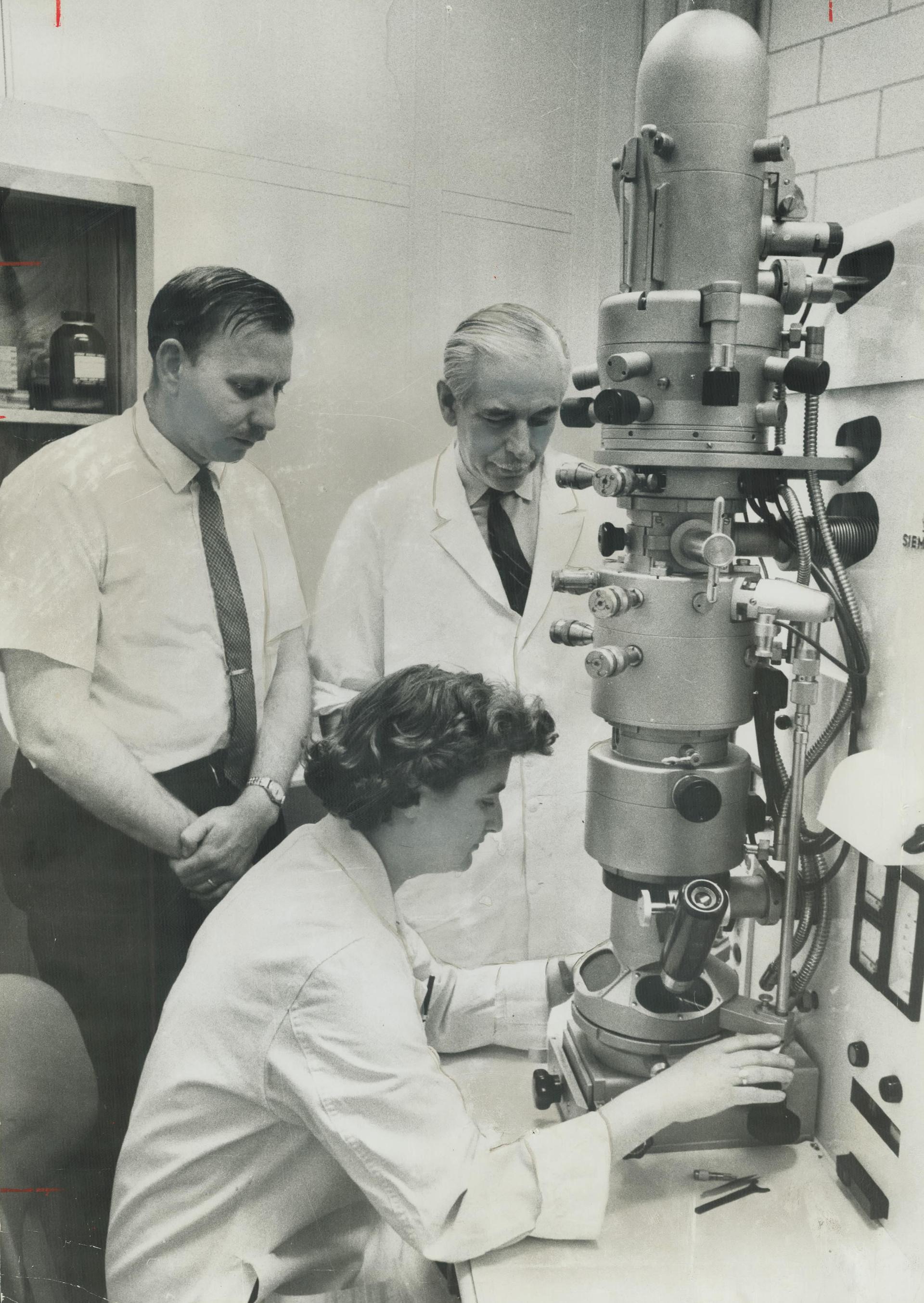

By her 30s, Scottish virologist June Almeida had already developed new techniques to better visualize and identify viruses using an electron microscope.

She was not only a pioneer of virus imaging: Almeida also played a pivotal role in identifying the first human coronavirus, the same type of virus with tiny spokes as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that is causing the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 1964, while Almeida was working at St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School in London, she started to collaborate with other scientists on research about the common cold. One sample of a nasal swab, known as B814, was of particular interest to researchers. They found that type of virus could transmit common cold symptoms to volunteers, but researchers were unable to identify it and grow it in routine cell culture.

The research team sent samples of B814 to Almeida to study. With virus imaging, she described it as an influenza-like virus, but not exactly the same. Under a microscope, the B814 had a halo-like structure and was eventually named corona, the Latin word for crown.

Related: COVID-19: The latest from The World

Almeida identified the first coronavirus — and produced first visualizations of other viruses like rubeola, or measles. But her work in the field of virology has gone largely uncelebrated.

Now, 13 years after her death, the COVID-19 pandemic has made her work more relevant than ever.

Hugh Pennington, an emeritus professor of bacteriology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, used to work with Almeida at St. Thomas’ Hospital Medical School in London. He spoke with The World’s host Marco Werman about Almeida’s research and legacy.

Marco Werman: How well did you know Dr. Almeida, Hugh? What did you work on together?

Oh, I knew her very well. We were good friends. June spent most of her time at the electron microscope down in the medical school basement in the dark. She got into this kind of empire very jealously. I was working on quite different things upstairs, but we published a paper together on models of viruses and how you could simulate them using X-rays. I knew June very well, and I regard her as one of my most important scientific mentors. She was really a very interesting person to collaborate with and somebody who gave me an enormous start in my career.

Almeida was working at St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School in London when she was asked to help with this virus. They were calling B-814. What was that sample and what did she do with it?

She was really very good at having a network of people that she collaborated with, like David Tyrrell from the Common Cold Research Unit in Salisbury, who was trying to isolate common colds and identify them. He had this virus and he said, “Well, June is the obvious person to see what it is.” So that’s where her breakthrough occurred when she saw the virus and she said, “A-ha, here is a new group of viruses,” identified by the spikes with the knobs that we’re all very familiar with now.

Of course, thereafter, coronaviruses didn’t seem to be terribly important. They didn’t cause serious illnesses, so they remained as curiosities for years until SARS came along and now, of course, COVID-19. She had a hand in giving the virus the name coronavirus.

And she would have been amused that her name is now common currency everywhere. I don’t think she would be going around claiming credit. She would just say, “Well, that was a piece of work I did. How nice.”

So as the world is currently seized by this pandemic, what occurs to you about the kind of legacy June Almeida leaves behind? I mean, why did she remain obscure for so long?

I don’t know. She’d done some really good work on other viruses. I suppose she didn’t seek publicity. She didn’t need to. She had the links that she developed with other scientists. So people came to see her, bringing her material to look at.

What June was doing was really important work, but it wasn’t the sort of work that gets on the news in the evening on television or anything like that. She was just discovering things.

I have a scar on my arm, which is one of my June Almeida legacies. She and I agreed that it would be worth trying to grow a human wart virus, which was a virus she was interested in. And so she persuaded me to have a bit of my skin taken off on my arm to try and grow the human wart virus in a rather similar way to the way that the coronavirus is being grown.

Unfortunately, we were not successful. But I have this badge of honor, which, you know, I guess, I see June Almeida every morning. She was good at persuading people to do things. She persuaded me to have a hole cut on my arm. So suppose that tells the story really quite nicely, what June was like.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?