The chloroquine chronicles: A history of the drug that conquered the world

An old drug is getting a lot of new attention around the world: chloroquine.

In the United States, President Donald Trump has talked about the drug’s potential for treating the novel coronavirus, though there’s little evidence. Primarily used to treat malaria, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, chloroquine’s link to COVID-19 has prompted a global rush on the drug — and led to shortages.

But the clamor for the drug leaves leading scientists alarmed. The hopeful claims are unsubstantiated at this point, they say, even as scientists rush to set up trials to catch the research up to the hype.

Related: Trump’s medical advice triggers run on malaria drugs in Mexico

A historic pandemic and sought-after plant

The race for chloroquine is far from new. This remedy and its natural derivative, the cinchona plant, have defined world powers and symbolized hope for cures to destructive diseases for centuries.

“There are such clear parallels between what is happening now and what happened in the 17th century,” said Fiammetta Rocco, author of “The Miraculous Fever-Tree,” referring to a malaria pandemic that hit Italy especially hard in the 1600s.

Many thought the illness, with its spiked fevers and shaking chills, came from noxious fumes. Instead, it was the parasite-carrying mosquitoes populating Rome’s many marshes that spread the disease. Malaria — Italian for “bad air” — killed the Pope in 1623. The Vatican shut down, and 10 of 55 cardinals died, said Rocco, who is also a culture correspondent for The Economist.

Related: Climate change will make animal-borne diseases more challenging

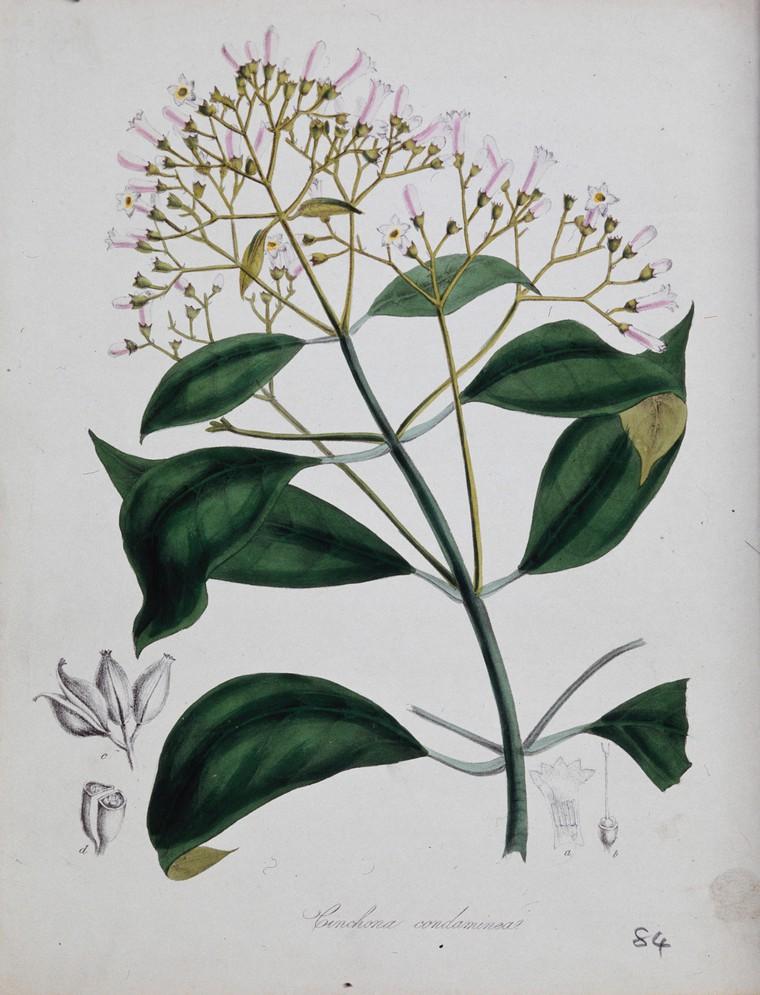

Looking for a treatment for the disease, priests from the Jesuit Roman Catholic order set out on a scientific expedition and mission, traveling as far as the Andean region of South America. It was there that they found the cinchona plant.

“You have to imagine … these huge, sort of botanical creations through which very little light even passes into the ground, they’re so huge,” said Rohan Deb Roy, a historian at the University of Reading in the UK and author of “Malarial Subjects.”

The Jesuit missionaries and Spanish conquistadors first observed how locals used the bark of the plant — or “fever bark” — to treat malarial fevers, Deb Roy said. They then brought it back to Europe.

‘A tool of empire’

“Whatever cured malaria should be understood not just as a medicine, but also as a military weapon,” Deb Roy said.

Malaria could kill more soldiers than bullets during war, and being able to fend off the disease became key to maintaining European colonies overseas.

“The cure for malaria would be then seen as a tool of empire,” Deb Roy said, “enabling soldiers to survive in these sort of unpredictable tropical colonial landscapes, which otherwise would be impossible for them.”

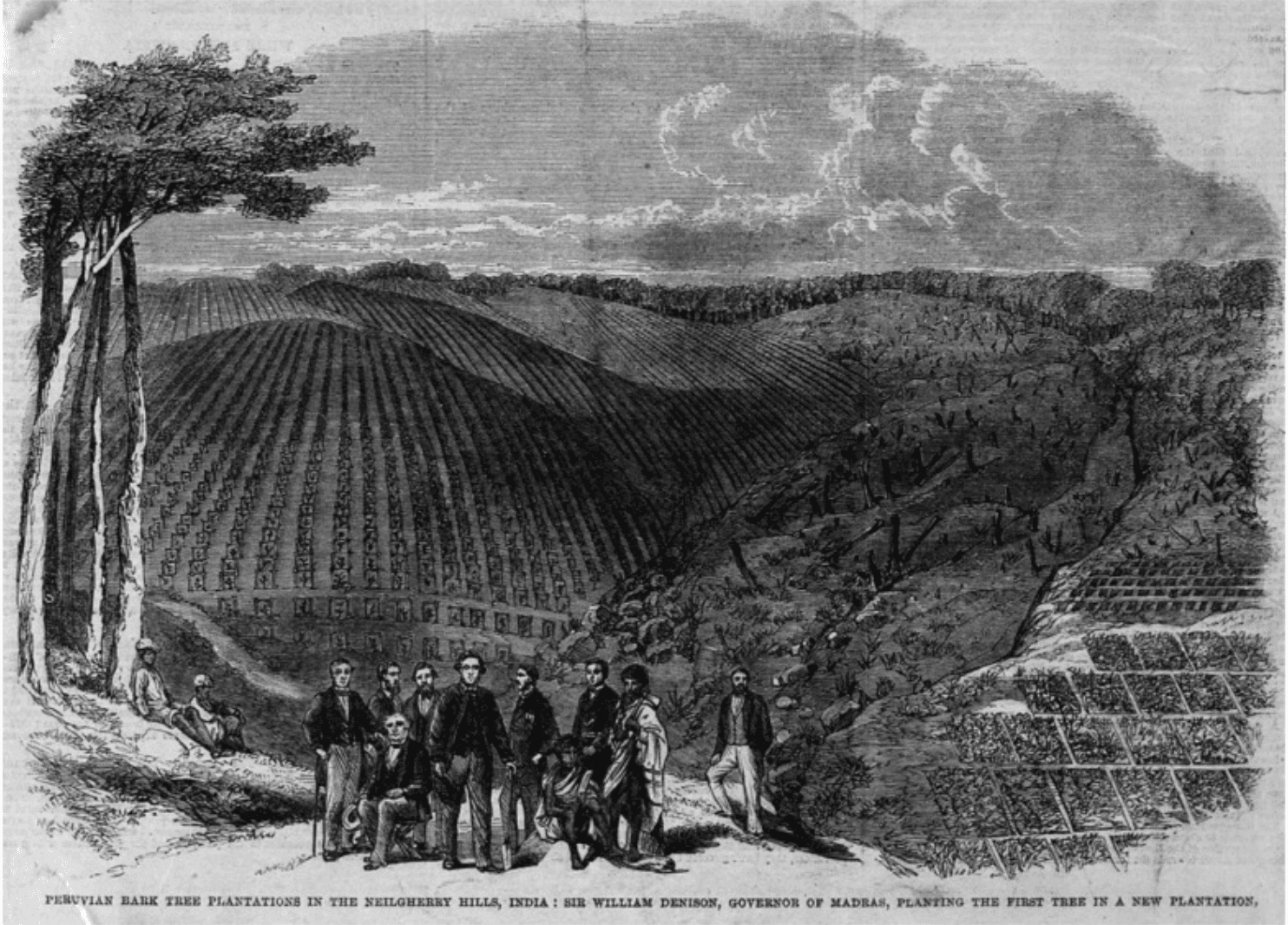

That led to a race among rising industrial powers to grow their own cinchona to lessen their dependency on Spain’s monopoly over the plant in the Americas. The Netherlands ultimately succeeded in the territory of Java, present-day Indonesia.

But how the bark actually worked remained a mystery until 1823, when two French researchers discovered the compound that made the bark effective against malaria: quinine.

Related: Lessons from Singapore and how it handled SARS

Quinine became the basis for many antimalarial drugs, though it took scientists another century to create a synthetic variation that would allow labs to manufacture the drug without any dependency on natural plants. Those research efforts picked up around World War I, when malaria posed a threat to all sides, including US soldiers training in the South.

“We often forget now that malaria was all over the place. All up through the Mississippi Valley there was malaria,” said Leo Slater, a chemist and author of “War and Disease: Biomedical Research on Malaria in the Twentieth Century.”

In the early 20th century, the natural version of quinine — from grinding the cinchona bark — was still the essential weapon against the malaria parasite. But when Japan took control of the Dutch East Indies during World War II, that natural supply was halted.

“When they do this, they cut off the rest of the world from the supply of quinine just as the war is coming,” Slater said.

The US significantly ramped up its own anti-malarial efforts during the war.

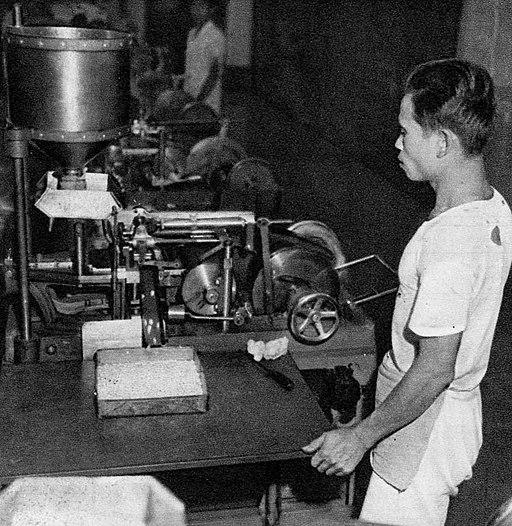

“They developed a large program, the largest of its kind and a model for post-war biomedicine to look for new drugs,” Slater said. “But the centerpiece of it was to test more than 14,000 compounds against malaria in one form or another.”

In the rush to arm US soldiers with anti-malaria medication, the military narrowed in on Atabrine, a drug that was effective, but incredibly toxic, causing soldiers intense nausea.

“They didn’t want to take it,” said Karen Masterson, a professor at Stony Brook University and author of “The Malaria Project: The US Government’s Secret Mission to Find a Miracle Cure.” “They were so resistant to it that the chain of command demanded that their unit commander put the pill in their mouth, close their jaw, and watch their Adam’s apple go up and down and swallow it.”

Related: Coronavirus most challenging crisis since World War II, UN says

During the war, Germany under Adolf Hitler had also put significant efforts into malaria research, including testing drugs on people in state hospitals, prisons and concentration camps, Masterson said. (The US also used non-consenting patients as test subjects in malaria drug experiments.)

By the end of the war, the US turned to a drug more tolerable than Atabrine. It had been developed, but not pursued, by German company Bayer, which had been pivotal in modern pharmaceutical practices and malaria drug experiments. The Bayer drug had also been used in experiments by a French doctor on residents of a German-occupied compound, Masterson said.

That drug was chloroquine.

A ‘miracle drug’

By the late 1940s and ’50s, chloroquine became “one of the miracle drugs,” said chemist Slater.

As the world entered a new era of peace, this “miracle drug” was promoted by the newly formed World Health Organization to help people across the world prevent and treat malaria.

Though chloroquine rose to fame quickly, its success didn’t last long, said Masterson. The so-called miracle drug was so widely promoted that malaria parasites developed a resistance, creating even more challenges in some communities where malaria was already endemic.

“It’s not a perfect drug, it’s not a magic bullet,” Masterson said.

Now, more than 50 years later, chloroquine, and its close relative, hydroxychloroquine, are in the spotlight again, as the world searches for a weapon against the new coronavirus threat.

“I’m not at all surprised that such a significant and major drug that is chloroquine is back in the news in the context of a global pandemic,” Deb Roy said.

COVID-19: The latest from The World

Today, chloroquine still has important medical uses, but it can have serious side effects — even death for some. In the fog of a fast moving pandemic, no one knows yet whether it’s actually useful against COVID-19.

Still, chloroquine — the product of magic plants, dead popes, and desperate hopes — has again come to represent a glimmer of light for some leaders today.

But Masterson cautioned that it represents something else, too.

“To me it’s a symbol of false hope,” she said.