A Uighur poem of ‘unimaginable suffering’ travels from Chinese internment camp to New Jersey

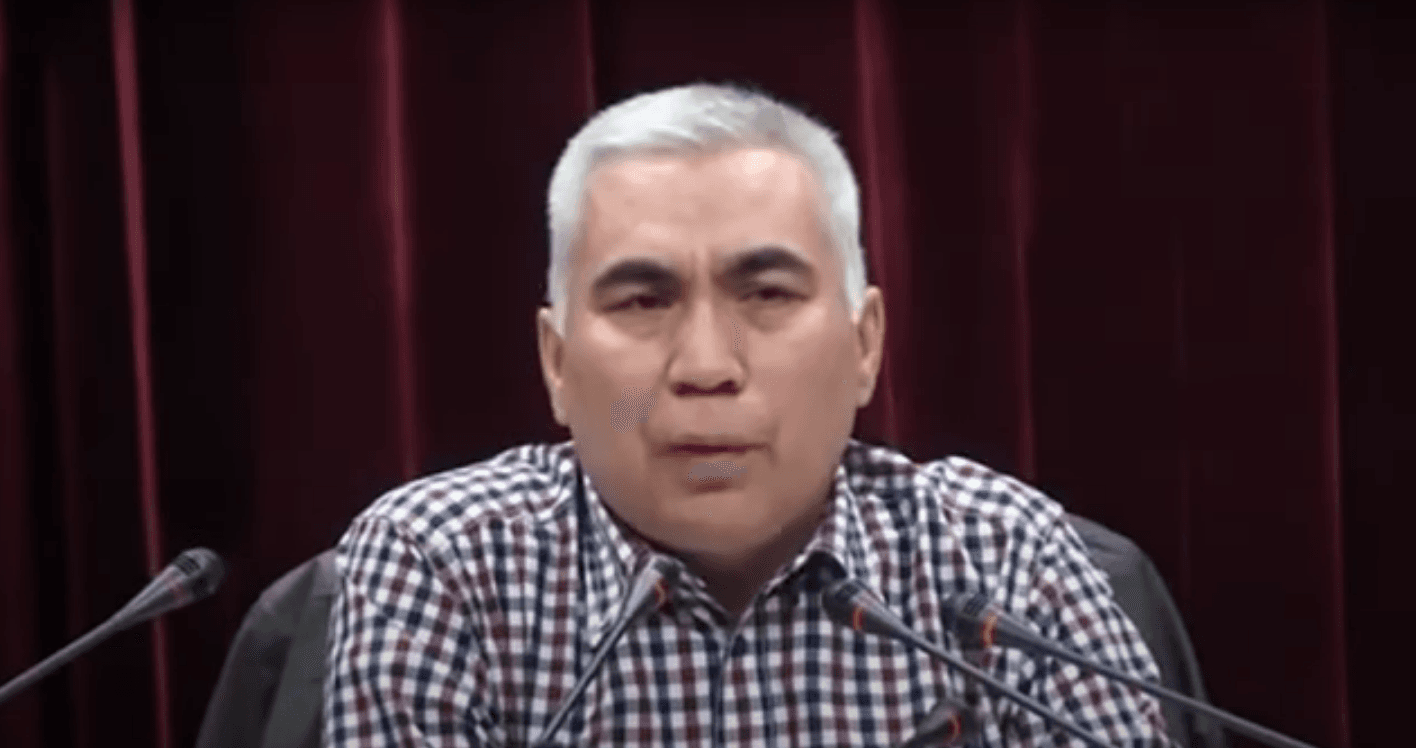

The last time historian Joshua Freeman saw his former professor Abduqadir Jalalidin was in 2016, when they were sharing drinks and stories in Jalalidin’s apartment in the city of Urumqi, China. Jalalidin, a famous Uighur poet, and Freeman, a translator of Uighur poetry, also share a mutual interest in Uighur history and culture.

Less than two years later, Freeman learned that Jalalidin had been one of the million-plus Uighur people sent to China’s so-called “reeducation” camps. These camps are widely reported to be part of a vast, coordinated campaign by the Chinese government to persecute and forcibly assimilate Muslim ethnic groups in the Xinjiang region of northwest China.

Related: French politician aims to expose China’s concentration camps

After years of silence, Freeman finally heard from his former professor in an unexpected way — in the form of a poem.

“What I learned is that even in the camps, my old professor had continued writing poetry,” Freeman said. While he can’t know for sure, Freeman believes that fellow camp inmates had memorized Jalalidin’s poem and it spread by word of mouth outside the camp gates, eventually reaching Freeman in New Jersey.

“I was deeply moved that other inmates had managed to get this poem beyond the camp. I felt that this was a witness that the world needed to hear, that this was a testimony the world needed to hear.”

“I doubt that Abduqadir ever expected that this poem was going to reach me,” said Freeman, who is a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University. “I was deeply moved that other inmates had managed to get this poem beyond the camp. I felt that this was a witness that the world needed to hear, that this was a testimony the world needed to hear.”

Related: Experts: China’s Uighur population control meets criteria for genocide

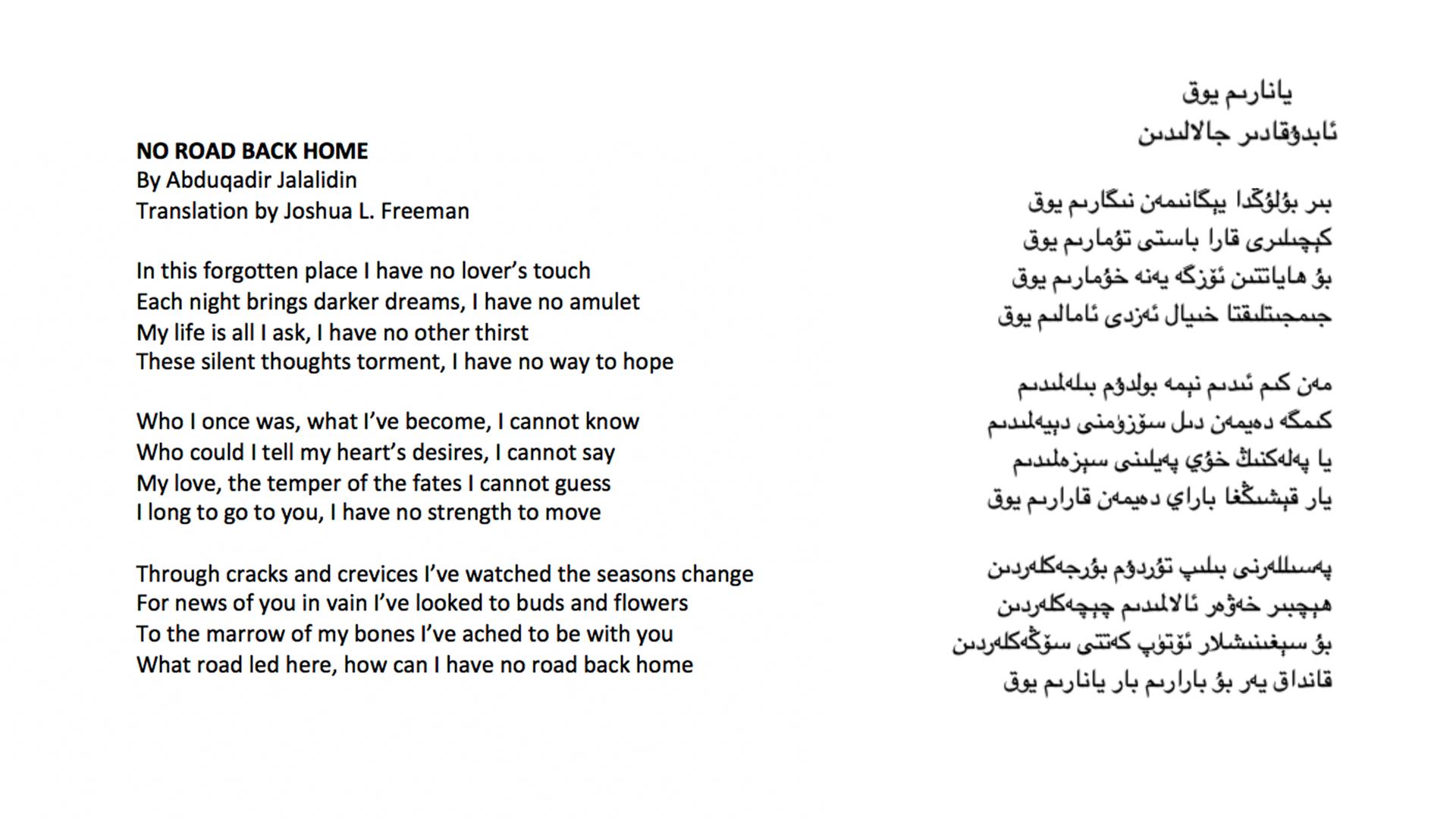

Freeman translated the poem from Uighur into English and began sharing it on social media. The poem, “No Road Back Home,” is a mournful expression of being trapped in a hopeless situation, of yearning for community and home.

Freeman said he was profoundly moved when he first encountered the poem.

“I think about what’s happening in the Uighur region all the time, but this was one of the very most affecting and direct documents I’d ever encountered from the unimaginable suffering that’s happening there right now,” Freeman said. “You know, amidst all of the suffering and hopelessness, there is the resilience and the courage and the creativity of writing this poem.”

Poetry is a powerful force in Uighur culture, said Freeman, who often posts Uighur poetry and his translations on his Twitter page. The fact that many people memorized Jalalidin’s words is a testament to that.

Related: Data leak gives insight into China’s Uighur detention

“Many of the best-known and most influential and most loved documents of Uighur history are poems,” Freeman said. “This poem is a very important document of what’s happening right now.”

Memorizing a poem like this one can help suffering Uighurs connect with their love for their language and shared history, Freeman said. It’s also a significant act in the face of China’s targeted attacks on Uighur culture and traditions.

“In terms of Uighur continuity and in terms of self-preservation and in terms of keeping one’s spirits up amidst an impossible situation, I think poetry has that … direct role here.”

“In terms of Uighur continuity and in terms of self-preservation and in terms of keeping one’s spirits up amidst an impossible situation, I think poetry has that … direct role here,” Freeman said.

As for this poem’s impact on the plight of Uighur people, it depends on whether people around the world are willing to stand up and do something, Freeman said. “Is the world going to stand silently, or is the world going to listen?”