Kenya launches Oxford Astrazeneca vaccine trial amid second wave of coronavirus

After weathering the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic with relatively few cases, Kenya is now experiencing a dangerous second wave. Intensive care unit beds are filling up in the nation’s hospitals, and the number of people who have died has now passed 1,300.

As cases continue to rise across the country, Kenyan scientists in the beachside destination of KIlifi are hard at work on the country’s first COVID-19 vaccine trial.

On Oct. 30, Kenya Medical Research Institute Wellcome Trust, which is leading the study, launched a phase one trial of the Oxford Astrazeneca vaccine candidate, also known as the ChAdOx1 nCoV-2019.

The global trial has enrolled more than 24,000 participants from across the world, including in the UK, South Africa and Brazil. On Monday, the University of Oxford, citing interim trial data, said the vaccine’s efficacy could reach 90%.

Professor Andrew Pollard, chair of the Oxford vaccine group, recently told The Guardian that the trial results could be released before Christmas.

“We expressed interest in evaluating this vaccine in Kenya because we think that it is important for vaccines to be shown to work in all populations.”

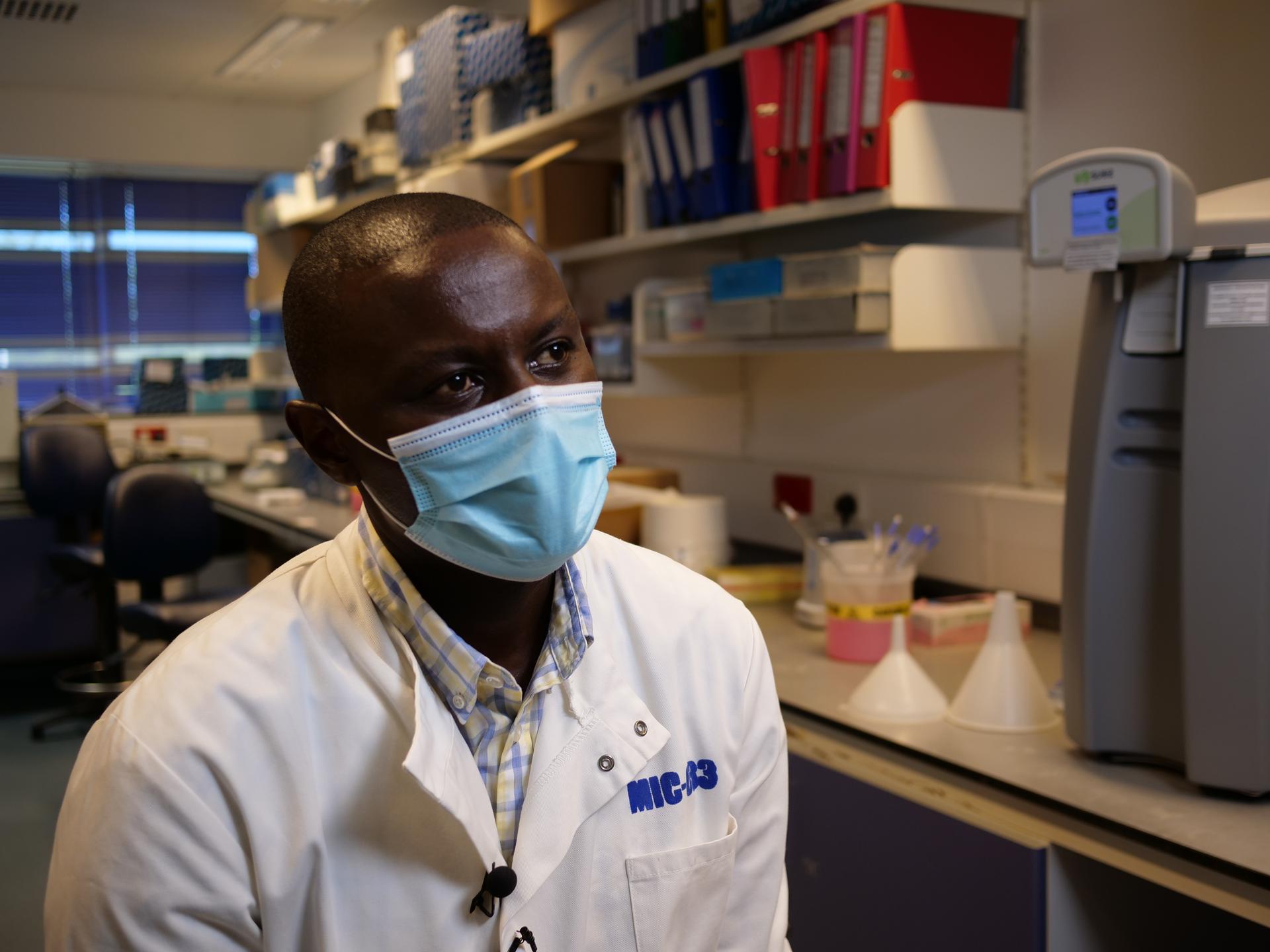

“We expressed interest in evaluating this vaccine in Kenya because we think that it is important for vaccines to be shown to work in all populations,” said KEMRI’s principal investigator, George Warimwe.

“Obviously, we cannot assume that the immune response observed in one setting, say, Brazil, that those will be comparable to what we see in Kenya,” he explained.

One also can’t assume that every vaccine will be suited for every environment. Although other vaccines like Moderna and Pfizer have announced encouraging immunity results, variations in temperature and storage requirements will require countries to make decisions about which vaccine is feasible to roll out in their environments.

Related: How mRNA vaccines work so brilliantly and why they must be kept so cold

The Pfizer vaccine, for example, will require storage at ultra-low temperatures, which might not be feasible in all settings.

“You can imagine trying to have this sort of freezer in all the different places in the world. Some of them, very rural. It’s a much more complex process,” Warimwe said. “We’d prefer to have a vaccine at room temperature. Or one that requires less energy requirements where it’s just keeping the fridge at 2 to 8 degrees.”

The Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine, on the other hand, can be stored at “fridge temperature,” between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius, according to the University of Oxford.

The trial in Kenya has already begun injecting its first volunteers and will target 40 health workers in phase one before expanding to 400 front-line workers, including security guards and truck drivers, in the second phase.

Related: Sweden’s pivot toward new virus restrictions may not ‘shift mindsets,’ says Swedish scientist

“They are the highest risk of exposure,” Warimwe said, explaining that front-line workers will likely be the top targets for the vaccine candidate if successful.

For many health workers, a vaccine can’t come soon enough. The second wave of COVID-19 is taking a toll on health workers. Four doctors died in a single weekend earlier this month, and the Kenyan Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists and Dentists Union has issued a strike notice for December.

At Kilifi County Referral Hospital, cases have been manageable, says Patrick Nzaka Mbagande, a nurse who was recently transferred to the hospital from nearby Malindi due to a shortage of health workers.

Less than an hour away, in Mombasa, the situation has been direr, says Mbagande, who recently transferred a sick health worker there.

“I was amazed when I reached Mombasa, seeing the ICU packed and people dying in the corridors. It was very devastating.”

“I was amazed when I reached Mombasa, seeing the ICU packed and people dying in the corridors. It was very devastating,” he said, grimly shaking his head.

Nurses and other health workers who aren’t infected by the virus are impacted in other ways.

Mbagande, who was at the end of his one-week rotation at the COVID-19 isolation unit, will have to quarantine for two weeks at the hospital’s living quarters before being able to visit his wife and newborn child.

Related: Pandemic set to widen global inequality

Cooped up inside can be lonely and isolating. Still, Mbagande notes some people in the surrounding communities still doubt the existence of the disease, or at least the harm that it can cause.

“Even right now they are often asking me. Is this thing real?” Mbagande said. “We even have patients, they don’t believe there are positive cases here in Kilifi County hospital.”

The misinformation poses its own challenges when it comes to recruiting for the vaccine trial, says Salim Hamis Mwalukore, community liaison manager for KEMRI.

Mwalukore essentially serves as the middleman between KEMRI’s vaccine research team and the surrounding communities in Kilifi County, where the first round of volunteers are being recruited from.

“Understanding how vaccines work is also an issue,” said Mwalukore, adding that he is often asked, “So, you are giving me that thing that really can cause me the disease?”

The pandemic itself also makes recruitment hard.

“I think this vaccine has been slow compared to other vaccines,” Mwalukore said. “But also, we are aware that the engagement process is different,” he continued, noting how much of the early outreach has to be done remotely.

Related: Study shows Black people twice as likely as whites to contract coronavirus

Mwalukore has been reaching out to truck drivers, health workers and security guards to spread awareness about the trial. One person he met with recently was Washington Omondi, a security guard professional who also lives in Kilifi. Like other front-line workers, Omondi feels especially at risk due to his work.

“The guards have contact with so many people every day. The fear of having the virus is there. But then, you do not have an option. You have to do the work,” he said.

Omondi says many security guards are interested in participating in the vaccine trial.

“Most of them are interested in the curiosity of how will this one help me? How is this one going to help me live a free life?”

For Omondi, it’s also a matter of duty.

“As a security man, you must be at the forefront of saving life,” he said. “If I’ve got the opportunity to save someone’s life, I should do it.”

He plans to sign up once the trial moves to its second phase.