At first glance, the 25-year-old woman pushing her son on the swings and cradling her baby looked like a typical mother in Mexico City. But instead of taking her children to the neighborhood playground, she watched over them in the yard of a shelter for women fleeing violence. That’s where they’d been living — or rather, hiding — for the past few days.

“I was always the one at fault, no matter what he did,” she said.

The “he” in question was her husband. And the woman, who asked The World not to use her name for fear he would find her, said she might have stayed with him had it not been for the murder of another woman exactly her age. In early February, Ingrid Escamilla was found murdered, her lifeless body skinned. Her 46-year-old husband was arrested at the scene while covered in bloodstains. Photos of Escamilla’s mutilated body flooded the news.

The woman in the shelter looked at the photos and thought: That could be me one day. So she fled.

“But at the end, the violence was getting worse and worse. I knew that in a few years, I could be that woman on TV.”

“Maybe not tomorrow, or this month,” she said. “But at the end, the violence was getting worse and worse. I knew that in a few years, I could be that woman on TV.”

In Mexico, Escamilla’s killing — followed days later by the kidnapping, rape and murder of a seven-year-girl outside her school — has sparked outrage and calls for strikes to protest violence against women. The issue has led the news in Mexico for weeks. On March 8, International Women’s Day, marches are expected to take place around the country. The following day, March 9, feminist organizations are organizing a “day without women” — urging women not to appear in public in order to protest gender-based violence.

The topic is turning into a political crisis for President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has struggled to contain growing discontent and articulate a response to the outrage. His approval rating fell to 59% this month, down from 78% a year earlier, according to a poll by the Mexican newspaper Reforma. Despite his promises to address the brutal killings of women and girls, his administration has cut programs aimed at helping them.

“Look, I don’t want the topic to be only femicide,” he said last month at his daily press conference, referring to the murder of girls and women because of their gender. The concept of femicide is similar to that of a hate crime. The number of reported femicides in Mexico is rising, up 10% in 2019 from the year before.

A few days after the press conference, López Obrador suggested femicides were a result of the “neo-liberal policies” of his predecessors. Mexican society, he said, “fell into a decline. It was a process of progressive degradation that had to do with the neoliberal model.”

Related: Instagram art project spreads awareness about femicides in Mexico

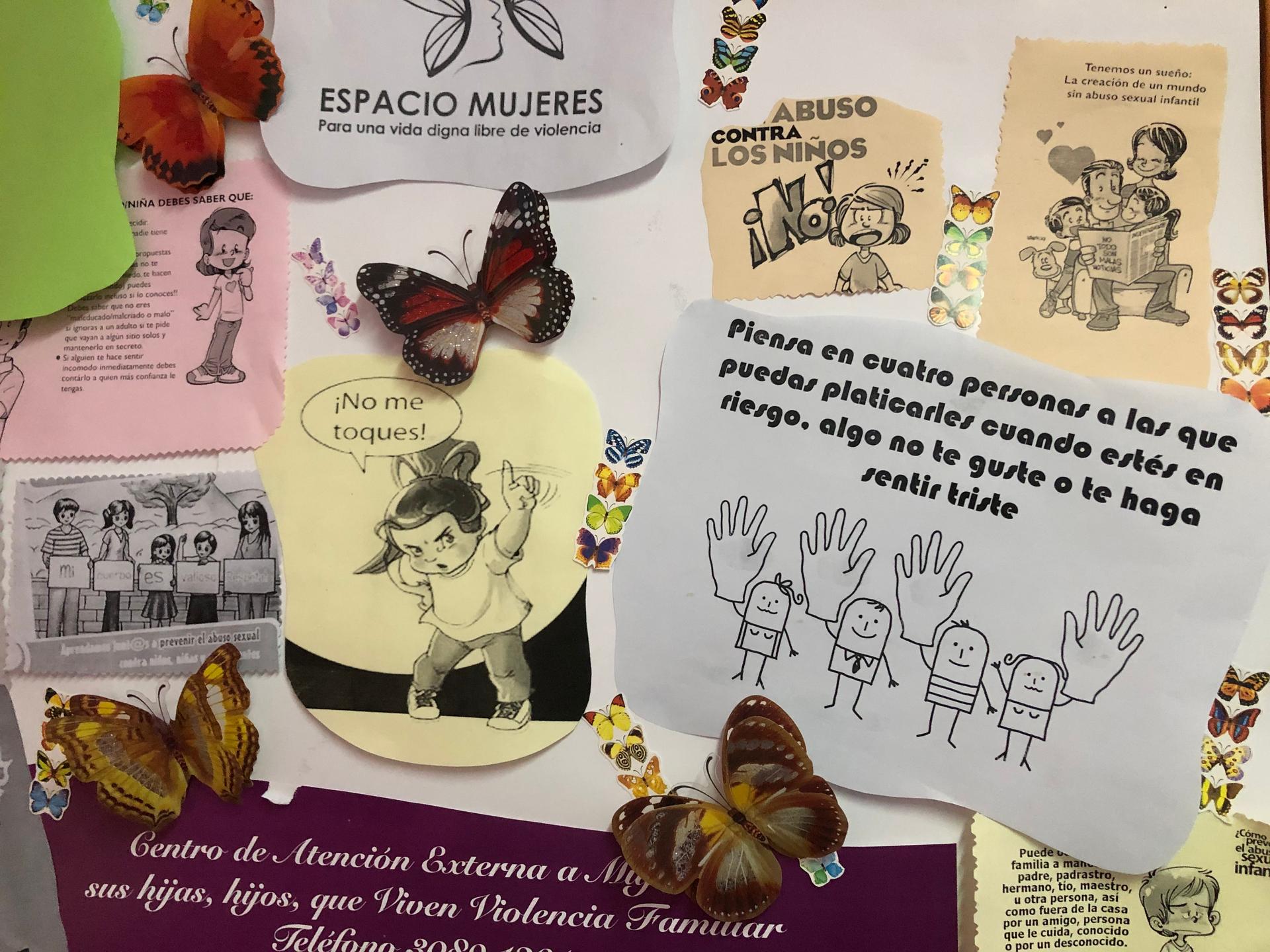

Funding cuts for women’s shelters

Some activists saw these comments as dismissive — and in line with his policies. Since taking office in 2018, López Obrador cracked down on funding for programs that support women, from shelters to government-supported daycare. The president said the nonprofits that run them aren’t transparent with their finances, and that it would be better to give money to women directly.

“This speaks to a completely distorted vision,” said Wendy Figueroa Morales, who oversees a network of shelters for women across Mexico. She said giving money directly to women does nothing to address the problem of domestic violence, which is a leading cause of femicide. In addition, she said that government-funding for daycares gives women independence and autonomy.

“López Obrador is taking us years backward,” she said. “Away from what we have achieved at an international level.”

Funding for many shelters has been slashed. The shelter where the 25-year-old woman and her two children stayed in Mexico City lost half its staff in January because of budget cuts. Now, instead of six social workers and nurses, it has two. The women staying at the shelter — who range in age from 18 to 72 — are taking on most of the chores, including cleaning and cooking. The shelter is guarded by a single security guard who keeps tabs on everyone coming and going, and what cars are parked outside.

A culture of indifference toward women

Figueroa Morales and other activists acknowledge that Mexico has many laws to protect women. They’re just not enforced.

One of the biggest problems is indifference, some women say. The woman at the Mexico City shelter, for example, sought help from the police in November to escape from her violent husband. She said the police told her they see a lot of women like her like her filing complaints against their husbands, and that the process was a waste of time. They encouraged her to return home to her husband.

And it’s not just the police. One nurse who works at the Women’s Hospital in Mexico City said hospital staff are often indifferent to violence against women. The nurse, who asked to withhold her name because she still works at the hospital, recalled one occasion in particular: a woman who had been dumped there by her boyfriend. The woman was in shock because a hairbrush had been inserted in her vagina.

“The vagina was shapeless, deformed,” the nurse said.

But instead of showing the woman compassion, the hospital staff talked about her with disgust, she said.

“It was comments like, well, ‘she must have been really drunk not to notice a hairbrush in her vagina’,” she said.

Related: Femicide in Mexico

The Women’s Hospital said it had no knowledge of the incident. The hospital’s website says women who have suffered violence should receive professional intervention that doesn’t trivialize their trauma.

But the nurse said she never received a day of training about gender-motivated violence.

“It’s supposed to be a hospital for women, to help women. But confronted with this kind of situation, the staff is indifferent,” she said.

For some women in Mexico, the fight to stay alive can feel like a living death sentence. One mother has been living in shelters for two years with her son, changing locations every three months to avoid detection. Her husband works for the government, she said, she’s terrified he’ll use his connections to find them.

“I don’t know what’s next,” she said. “It’s what fills me with despair and terror. Because I don’t know how this will end.”