Artist Christine Sun Kim on ‘deaf rage,’ the Super Bowl and the power of sound

A transcript of the radio version of this story is available here.

When artist Christine Sun Kim performed the national anthem in American Sign Language (ASL) at the Super Bowl on Feb. 2, she hoped it would give the Asian Deaf community some comfort to see someone like her on national TV.

The moment reminded her of “All American Girl,” a TV show she used to watch as a teenager that featured Asian American actor Margaret Cho.

“To see a family on TV that looked exactly like my family …gave me so much comfort with my own identity,” said Kim, also known as CK, through an ASL interpreter. “And I’m hoping that I was able to do that, too, for the Asian Deaf community.”

Kim became the first Asian American Deaf woman to sign the anthem at one of the world’s most-watched TV events. She said she never could have imagined such an opportunity. She was invited by the National Association for the Deaf (NAD) and the National Football League (NFL).

But some people in the Deaf community — who use a capital D to identify themselves as part of a unique culture — expressed disappointment that Kim only got a few seconds of airtime.

“I was really excited about this one because it seemed like we finally were getting full coverage after years of misfires, and [Fox Sports] seemed serious about it, too,” Tyrone Giordano of Communication Service for the Deaf (CSD) told The World in an email.

“That excitement quickly turned to shock and disappointment when the camera pulled away from CK mid-song. In fact, it pulled away for both of her songs … It felt like we were just a token, and then once that ‘show Deaf people doing some hand-waving’ box was checked, they moved on. They forgot about us, and it hurt.” The World reached out to Fox Sports for comment but did not hear back before publication.

Kim was frustrated, too. She wrote about it in an op-ed for The New York Times. “Why have a sign language performance that is not accessible to anyone who would like to see it?” she wrote. “It’s 2020: We’ve had the technology to do so for decades.”

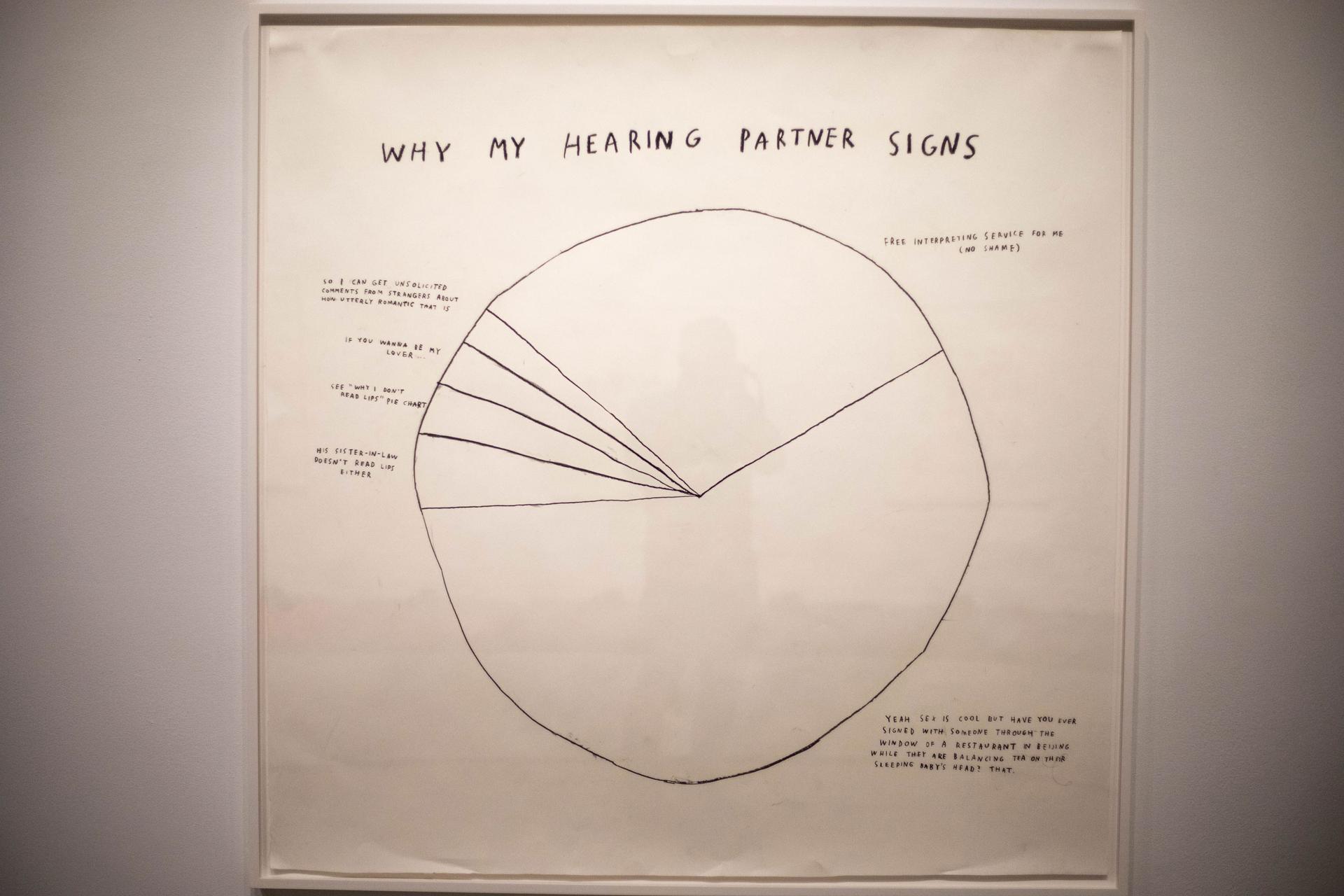

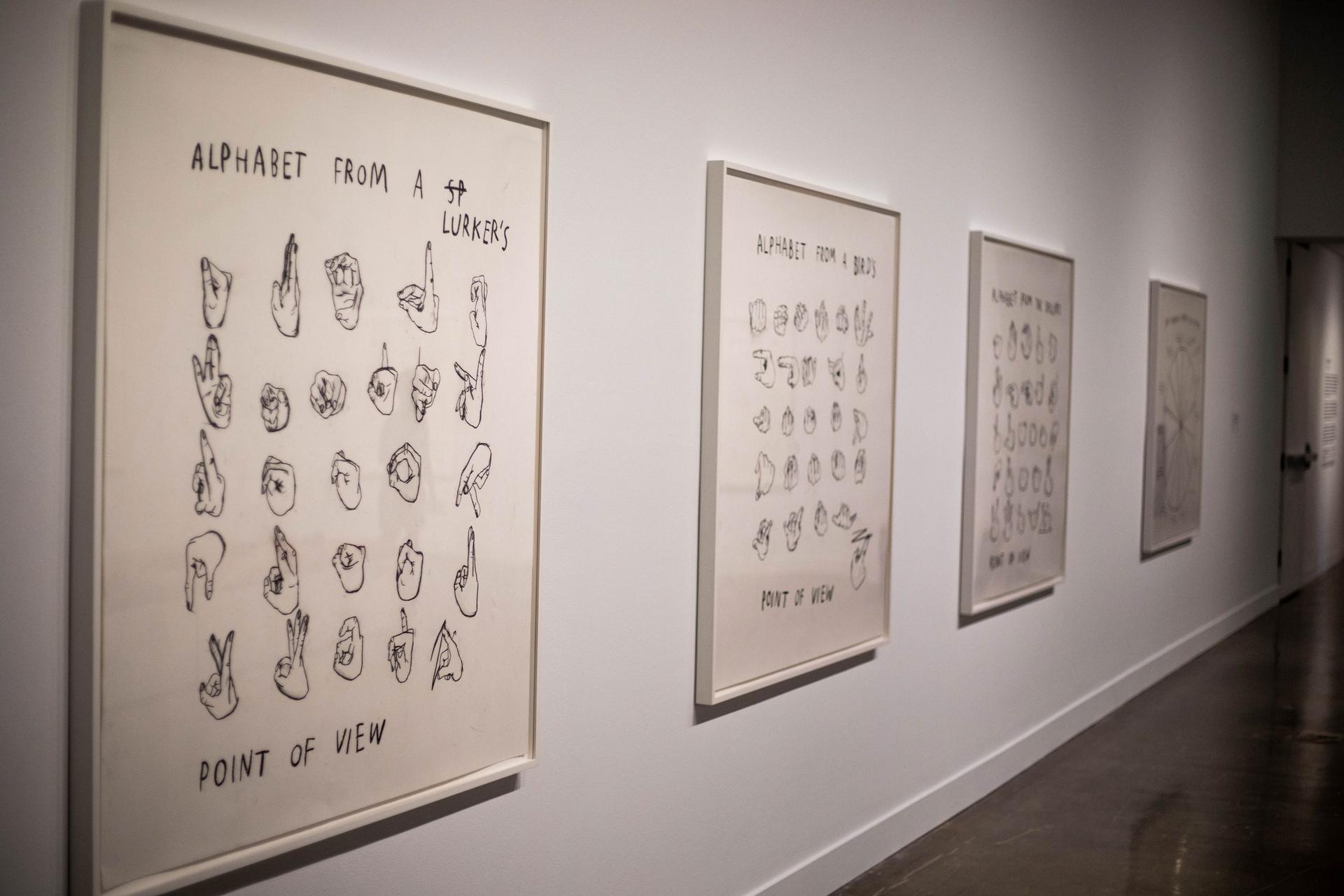

As an artist, Kim has used her art to channel much of her frustration on living with deafness in a world geared toward hearing people. She created a series of charcoal diagrams she calls “Deaf Rage.” And her current work, “Off the Charts,” on display at Boston’s MIT List Visual Arts Center through April 12, depicts personal decisions she has made as a Deaf person via pie charts.

“I always find that the best way to communicate with a wider audience who [is] not deaf is to use a format that people can easily understand,” Kim said. “It’s like mathematical angles. How much rage [do] I have? You can see it in that size of the angle.”

One chart explains why she doesn’t read lips. And another is called, “Why My Hearing Partner Signs.”

“They are actually quite profound and funny, but funny in a way that there’s a certain amount of absurdity in expressing a very personal decision in a diagrammatic pie chart form,” said Henriette Huldisch, the curator of Kim’s exhibit, and now chief curator and director of curatorial affairs at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

Huldisch said Kim’s art helps hearing people like herself learn from the Deaf community.

Hundreds of people gathered at Kim’s exhibit at MIT on opening night last week. There were dozens of ASL users who mingled and took selfies with Kim, who is petite with blunt, black bangs across her forehead. Friendly and expressive, Kim’s sense of humor is just as deadpan as her pie charts.

Kim’s art is not necessarily meant to fit a hearing person’s understanding of the world. But she said it took her a while to learn that.

Kim was born in California in 1980, when learning and using ASL was just starting to become more acceptable at home and school. Until then, deaf people were often expected to rely on lip-reading or hearing aids — even in deaf schools. Kim described the 80s as a period of a significant shift in attitudes around ASL.

ASL evolved from French Sign Language and has been in use in the United States for about 200 years, according to the National Institute for Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Today, more than 1 million people use ASL as their primary form of communication. There are 300 distinct sign languages across the world.

The politics of deafness

Kim says she can’t help being political in her art.

“There’s a long history of oppression, not enough support to American Sign Language. It’s exhausting, too, to deal with this,” she said.“Being Deaf [has] always been a political thing. I don’t know if it will ever stop being political. It would be nice to be Deaf and not have to deal with all of this, having to fight for everything and have this tension.”

She’s also an advocate for sign language.

“I truly believe American Sign Language is important because, from the beginning, when a child is born, if they learn ASL, they have full access to information,” Kim said. “That … can lead to other things [like] lip-reading or…a cochlear implant or something else.”

Unfortunately, there are many individuals who are “anti-sign language,” she said. In some developing countries, for example, a misconception persists that signing may harm a deaf or hard-of-hearing child’s development.

More awareness and acceptance for sign language would lead to better laws and access to quality of life and education, Kim said. While the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990 provided people like Kim access to interpreters for schooling and closed captioning, she said there is still a long way to go.

The CSD states that 70% of deaf people are unemployed or underemployed. The deaf community is also more susceptible to violence: In 2019, the CSD reported that 1 in 4 deaf women will be sexually assaulted in their lifetimes, compared to 1 in 10 hearing women. In her op-ed for the New York Times, Kim said that attacks and killings of deaf people by police motivated her to perform at the Super Bowl.

A better understanding of sign language would also create more visibility for deaf artists, Kim said. She can count the number of deaf artists she knows on her hands.

According to the CSD, 98% of deaf people do not receive an education in sign language in the US, and 72% of families do not sign with their deaf children, despite the shift that began in the 80s.

Still, Kim feels privileged growing up in the US, where educators and families began to embrace ASL. Her parents immigrated to the US from Korea and decided to learn English and ASL at the same time to communicate with their two deaf daughters.

“It [was] really one of the biggest examples of respect […] for me and my sister,” Kim said. “We felt seen, we felt valued, we felt important. Like, I am here, I exist. And growing up, that was an important feeling to have. And I think it helped me to develop a strong self-identity.”

Nevertheless, growing up was challenging for Kim. She says she didn’t feel like she found her place until she discovered visual art and felt safe in a world of visual images.

Seeing sound

In 2008, when Kim was at an art residency program in Berlin, Germany, her relationship with sound changed as she began to push her artistic boundaries. She visited galleries where sound was everywhere, and artists were producing sound as an artistic medium.

Growing up, sound had always been a “hearing person’s thing,” she said, But in Berlin, Kim said that sound was something she could see clearly in front of her.

At first, she feared that using sound in her art would make her “less Deaf” and faced a “cultural identity conflict.” But she discovered that sound gave her a voice and held a certain “social currency.”

“Society always prefers spoken language over visual language or gives weight to that…There’s value in spoken language.” Kim said. “…[O]nce I used sound in my work, I got all this attention…If I still kept discussing those topics but using a different medium, I don’t think I would have gotten the attention I did…”

As Kim continued to work with sound material in her art, she had an epiphany: “The Deaf community knows so much about sound.”

“We’ve internalized it. We know it so well,” Kim said. She defines “the sonic as a multi-sensory phenomenon, one whose properties are auditory, visual, and spatial, as well as socially determined.”

At the center of Kim’s exhibit in the MIT gallery space, she installed an audio installation entitled, “lullabies for roux (2018).” For this piece, Kim commissioned a group of friends to create alternative lullabies for her daughter, Roux, setting certain parameters such as omitting lyrics and speech and focusing on low frequencies.

Each song represents what Kim calls her “sound diet” for her child who is raised tri-lingually in ASL, German Sign Language (DGS), and German. She wanted to place equal weight on all three languages in a “culture that tends to ascribe lesser relevance to signed communication.”

Kim, now based in Berlin with her hearing partner and child, exhibits her art around the world. She said she hopes that people who see her work feel inspired to learn about sign language and the Deaf community.

“Often hearing people are the ones who are looking and creating history and we are just pushed to the side,” Kim said. “But as my art becomes bigger and I have a larger platform, I think it’s a nice way for me to look at myself almost as an archivist. I’ve made work. I’ve put it in history, and as that continues to grow, hopefully so does the awareness.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?