Just as a man donning a Santa hat rattles a bell, a bus pulls up in front of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem — the site believed to be Jesus’ birthplace. Tourists step out, led by a guide who holds a rod with a blue bandana at the tip. The busload of visitors kneels to enter the historical church through its notoriously small door.

Years earlier, the church was decrepit. It had a leaky roof, weak foundations, broken windows and grimy mosaics that were barely visible. Since 2013, a year after the United Nations declared the church a world heritage site, a large-scale restoration project has been undertaken to revive this sacred spot for pilgrims and visitors from around the world.

Related: Is Airbnb’s return to West Bank ‘whitewashing’ human rights issues?

Palestinian officials are hoping that the nearly-completed restoration will boost tourism at a time when the West Bank remains under Israeli occupation, plagued by a political stalemate and hobbled by high unemployment.

Anton Salman, Bethlehem’s mayor, estimates that 1.4 million pilgrims will make their way to the city, mainly to visit the church, this Christmas season. This is a 20% increase from last year, Salman said, adding that the number of visitors has been on the rise since 2017.

This year, Bethlehem is exuberant with the arrival of an important relic — a small piece of wood from the manger in which Mary laid Jesus after his birth — was returned from the Vatican.

“The relic is important because the nativity was taken [from us] and now a part of it has been returned. It’s part of the history of the city and part of Christmas history,” Salman said.

“But the church is the main attraction for people coming to the city,” he added.

The $17 million church renovation was financed by the Palestinian Authority and individual donors, churches and states, and largely carried out by an Italian company.

Afif Tweimeh, a Palestinian engineer overseeing the restoration project, said some 85% of the renovation has been completed.

Before and after

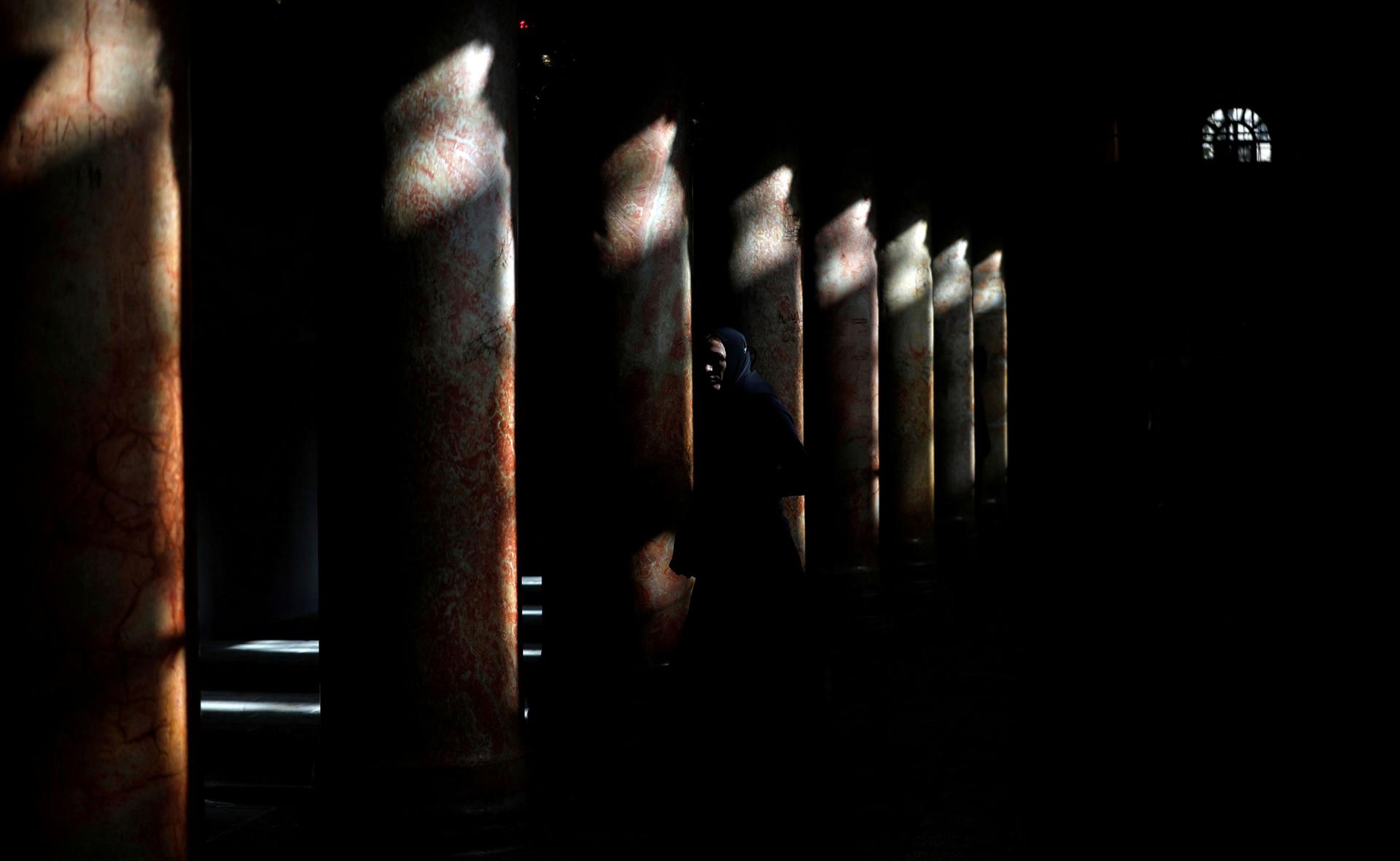

When they first started the church renovation, Tweimeh said, the roof was leaking, the wooden windows were broken, the wall mosaics were filled with grime and the paint on the columns was cracked. Today, the roof and windows have been restored, the wall mosaics shine, and the floor mosaics, along with most of the marble tiles, are transformed. In addition, renovators installed an electrical system, which includes lighting and smoke detection.

Now “you can see the wall mosaics,” Tweimeh said. “We have 125 square meters [149 square yards] of these mosaics. Before the restoration, all these areas were very dark and nobody could see their details. All these areas were cleaned well and they are now shining again.”

“Our plans for the near future is the installation of the microclimate system — this is part of the UNESCO requirement to protect the church — and other tasks like consolidating the south wall of the church to make it stronger against seismic action.”

Some work still needs to be done, Tweimeh said, including restoration of some of the stone and marble tiles, and the church’s front yard, all of which require an additional $2.8 million. “Our plans for the near future is the installation of the microclimate system — this is part of the UNESCO requirement to protect the church — and other tasks like consolidating the south wall of the church to make it stronger against seismic action,” he said.

The same restoration targeted the 50 columns inside the church, 33 of which depicted the images of saints and kings, dating back to the 12th century. During the restoration period, a thermographic scanner survey of all the church walls revealed a hidden mosaic: the church’s seventh angel. Another discovery, the team’s latest, revealed a small 1,500-year-old basin known as a baptismal font covered by a larger one.

“We removed the cement and concrete around it and we started to see some carvings. None of the original documentation we had talked about a font inside a font. So we believe that … it’s allowed the church to use the baptism for babies. Because the original one was for older people according to tradition at that time,” Tweimeh said.

A separate restoration of the church’s grotto remains unfinished due to two challenges: a $2 million shortage in funds and a disagreement between the three Christian denominations governing the church on how to go about renewing the altar crypt that marks the spot where Jesus was born.

Related: Spotify launches in Palestine for local artists

Bethlehem’s tourism limits

Bethlehem relies heavily on tourism, especially during Christmas. Despite its thriving holiday season, the town is still plagued by one of the highest unemployment rates in the West Bank at 21%, according to the Palestinian Statistics Bureau.

Bethlehem’s challenges are also compounded by the 23 Israeli settlements that encircle and isolate it. More than 165,000 settlers live there, comprising about 30% of the total settler population in the West Bank, according to Suhail Khalilieh, head of the settlement monitoring unit at ARIJ, a Palestinian research institute based in Bethlehem.

Related: For these vegans in the Palestinian territories, food is a form of protest

Settlements and the separation wall that cuts Bethlehem from Jerusalem — its historical twin city — have hemmed Palestinians into 13% of Bethlehem’s area, pushing many to emigrate.

“Development of the city is extremely limited,” Khalilieh said. “Lots of families emigrate, especially Christian families because there is no more land to develop. Land value has skyrocketed; people are unable to cope with these huge prices. I’m not talking about any prices. I’m talking about prices similar to [those in] New York and Tokyo.”

Bethlehem also loses out to Israeli-imposed restrictions that have made it nearly impossible for Palestinian tour guides to work on both sides of the Green Line, the pre-1967 war border.

“Today, we have hundreds of Israeli tour guides who are visiting Bethlehem, while we only have 46 Palestinian tour guides from the West Bank with Israeli permits to come and guide tourists across the wall.”

“Today, we have hundreds of Israeli tour guides who are visiting Bethlehem, while we only have 46 Palestinian tour guides from the West Bank with Israeli permits to come and guide tourists across the wall,” George Rishmawi, a tourism expert said, referring to Israel’s separation barrier that reaches roughly 30 feet in height in and around Bethlehem.

Israel first started building the wall in 2000, when the second intifada, or uprising, erupted. Parts of it follow the Green Line — the 1967 armistice border — and others cut deep into the West Bank.

Israeli tour guides take tourists to Bethlehem and then return with them to Israel for shopping and sightseeing: “We have an excellent tourism season this year. However, overall, business isn’t great. One of the problems is…tourists do their shopping and sightseeing inside Israel beyond the Green Line, and this is where Bethlehem is losing.

Yes, we may have tourists, but in terms of staying and going around Bethlehem and buying from Bethlehem, that’s a different story,” said Khalilieh with ARIJ, the Palestinian research institute.

Palestinians are hoping that, despite the obstacles, the restored Church of the Nativity, will market Bethlehem as a city worth visiting for more than a few hours.

“The church itself doesn’t need us to market it,” said Fadi Kattan, a renowned Palestinian chef from Bethlehem. “We’re really lucky with what we have here.”