These Argentine women fight against a justice system ‘written by men, for men’

Marcela Juan’s work is grueling, but important. As a prosecutor in Lomas de Zamora, a suburb 45 minutes outside of Buenos Aires in Argentina, she handles some of the area’s most disturbing cases. Juan specializes in cases of domestic violence, and femicide — the killing of a woman or girl based on her gender.

Juan has been doing this kind of work for over a decade and her caseload is full. She says that especially over the past four years, these types of cases have continued to rise. By her account, so far in 2019, at least one woman has been killed per day in this province.

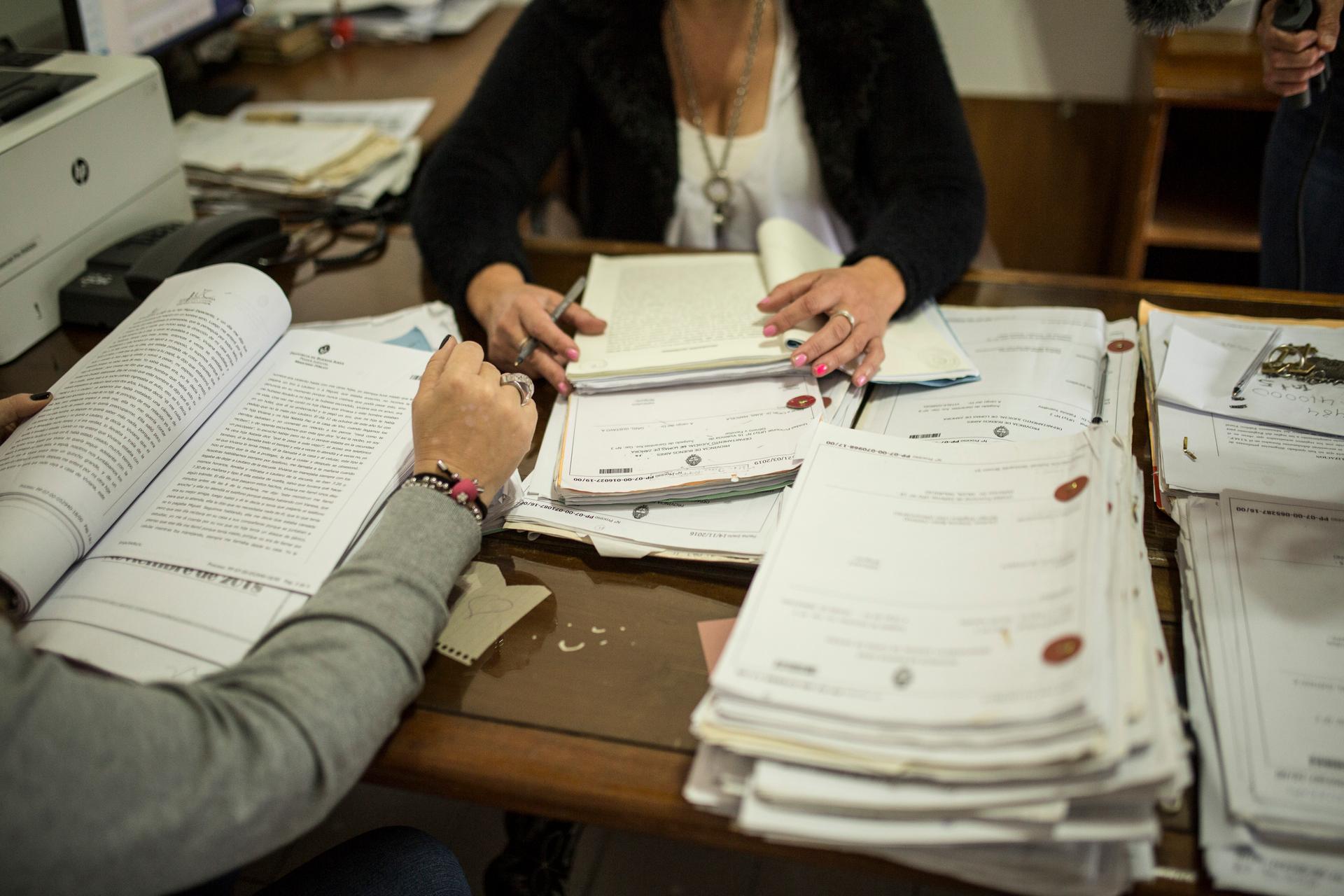

As a testimony to that fact, today marks Juan’s 15th day in a row in the office, and her desk is littered with stacks of papers laying out some of these horrifying crimes, which are all too common across Argentina.

Violence against women is rising nationwide — and Juan is among a number of women trying to solve the problem. Some are working on legislation while others are taking to the streets, making their voices heard.

Sometimes, this job is very daunting, but Juan says that ever since she can remember, she wanted to be a lawyer and fight for justice for women.

“Since I was a kid, I was always mediating disputes between friends. I was always defending someone who needed my help,” she said.

And, she has her daughter to think about. That keeps her going.

“I worry about my daughter because the realities I deal with at my job are cruel and more raw. Sometimes, I feel paranoid.”

“I worry about my daughter because the realities I deal with at my job are cruel and more raw. Sometimes, I feel paranoid,” said Juan, whose 9-year-old daughter’s artwork can be found in and among the piles along with used maté beverage cups in her office.

Related: ‘Maternity jail’: Women in Argentina and the US find ways around restrictive abortion laws

In Argentina, domestic violence and femicides are a huge problem. According to the Buenos Aires Times, in January 2019, at least 27 femicides were recorded across the country. That’s a sharp rise over last year when in the first month of 2018, 19 femicides took place in Argentina.

In Buenos Aires, some 46% of femicide victims were killed in their own homes, according to Mujeres de la Matria Latinoamericana (MuMaLá), a feminist advocacy organization in Buenos Aires. Almost 40% of the January femicides were committed with a firearm. Many of the perpetrators were the women’s partners or ex-partners.

Juan blames the misogynistic, conservative society where men consider women their property. She says there’s a profound lack of understanding of domestic violence in Argentina.

“This is a justice system written by men, for men.”

“This is a justice system written by men, for men,” Juan said.

Juan’s office is tucked away on a residential street in Lomas de Zamora, a poor area on the outskirts of the city. Paved roads give way to pockmarked streets. Some of the stucco houses that dot the neighborhood are neatly kept with flowers and the occasional mural of the Argentine saint, Gauchito Gil, painted on the side.

Related: Argentina is divided over abortion — even the feminists

This afternoon, Juan flips through one file — a murder case. She reads aloud the testimony from the slain woman’s family: “This is testimony from the mother of this woman. She says that her husband was very jealous. He controlled her cellphone; he made her stop caring for her other children from another man. And ultimately, he killed her.”

The case is about to go to trial, and Juan ordered the husband to remain in custody because she fears he won’t show up in court.

She says this kind of case is typical. Unfortunately, Juan never sees women in preventative stages — it’s always after the violence against them has become so severe, they’ve gone to the hospital, or they’re dead.

Roxana Fontana, one of Juan’s legal assistants, agrees with Juan’s assessment.

Sadly, she says, these cases often follow a familiar pattern: “These cases often start with a restraining order. Then the man doesn’t respect it, and the violence just keeps happening. Sometimes what happens is, a woman gets in a circle of violence where she doesn’t tell friends or family and then all of a sudden, she ends up dead,” Fontana said.

Juan says money for prevention programs or shelters does not exist in this city. Argentina is facing a growing economic crisis that has put many people out on the streets. In fact, people in her office must bring their own toilet paper. The window shades are falling apart, revealing a cracked window.

Related: Mandatory sex ed curriculum stirs controversy in Argentina

The state of affairs compounds the problem of violence against women.

“There is a lack of resources; women often have no places to go. There aren’t enough shelters or services so sometimes they just stay.”

“There is a lack of resources; women often have no places to go. There aren’t enough shelters or services so sometimes they just stay,” Juan said.

That’s something that Congresswoman Carla Pitiot is working on. She’s among a group of lawmakers committed to ending domestic violence. In January of this year, they called for President Mauricio Macri to declare a state of emergency after a surge in femicide cases were reported nationwide. Pitiot says while things are tough in Argentina, the laws are a model in the region.

“Femicide is specifically included in the penal code. If you kill a woman, it’s not only a homicide, but if you kill that woman because she is a woman, it’s a femicide. And, you have a longer sentence.”

“Femicide is specifically included in the penal code. If you kill a woman, it’s not only a homicide, but if you kill that woman because she is a woman, it’s a femicide. And, you have a longer sentence.”

Despite that law being on the books, Pitiot says there needs to be more training and more preventative efforts — and this requires a budget, something Argentina is struggling with right now. To Pitiot, the lack of money being spent on preventative efforts means more women die.

“The budget given to the agency in charge of creating policies for women only gave them 11 pesos per year per woman, which is basically the equivalent of 25 cents per year per woman. With that budget, you cannot apply any policies. And while these people say they care about women, they don’t give them the money to make a difference.”

One tool that can be effective — but needs better funding — is the crisis hotline that Pitiot championed four years ago. She says they are getting many calls but women who use it need services and direct help.

Pitiot has spent her career fighting for women’s rights. A painting of her hero, Eva Perón, hangs behind her desk in her office near the National Congress. Perón was the first lady of Argentina from 1946 until her death in 1952.

“She was my inspiration for running for office. She fought for the right of women to vote,” Pitiot said, pointing to the Andy Warhol-style depiction of Perón in her office.

Others have also put forward laws to protect women.

The Micaela Law passed last December. It’s named after Micaela García, a 21-year-old activist and student who was found murdered in 2017 in the city of Gualeguay, 140 miles north of Buenos Aires.

The law is aimed at training judges and law enforcement on how to better deal with cases of gender violence.

Earlier this year, prominent actress Thelma Fardin started to work with lawmakers on a bill that would remove the statute of limitations involving crimes of sexual abuse. Currently, the law is only aimed at prosecuting crimes that occur when a person is under 18. She wants to change it so the statute of limitations is removed for everyone.

It’s a cause that Fardin has a personal stake in. Her accusations of sexual abuse against actor Juan Darthés rocked Argentina late last year. She alleges that Darthés assaulted her in 2009 while they were both starring in the hit series “El Patito Feo,” or “Ugly Duckling.” Fardin was just 16 and Darthés was in his mid-40s.

Laura Azcurra is part of a 50-member collective of actresses that held a press conference in support of Fardin last December.

Azcurra says that as an actress, sexual assault occurs all the time in Argentina. And the actresses coming together, yes it was kind of a #MeToo moment for them.

“There was the historical aspect of that event. We didn’t realize it at the moment, but we were unraveling something that has been quiet for a long time and because, well, we called it an awakening for women.”

“There was the historical aspect of that event. We didn’t realize it at the moment, but we were unraveling something that has been quiet for a long time and because, well, we called it an awakening for women.”

The movement, with a hashtag by the same name, #NiUnaMenos or “not one woman less,” has also continued to gain momentum since hundreds of thousands of women called for a nationwide strike in October of 2016 to protest violence against women.

Juan says she’s glad this issue is getting attention.

“Yes, I’m glad we have these movements that encourage and empower women. But how many women have to die before we realize that it’s a problem. The numbers of women being killed are still so high.”

“Yes, I’m glad we have these movements that encourage and empower women. But how many women have to die before we realize that it’s a problem. The numbers of women being killed are still so high.”

New laws are one thing but a budget to make sure those laws are enforced is another. Argentina is in the middle of an economic crisis and many agencies, including the one Juan works for, are hurting.

She says that more money is needed not just for her and her staff but to protect women who are vulnerable and facing abuse.

In the end, Juan says, it’s good that there is more visibility given to cases like the ones she deals with, but for now, she’s still worried about the stacks of cases still on her desk — ones she hopes she can solve and bring closure for victims’ families.

Funding for this reporting was provided by the International Women’s Media Foundation.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?