8 things you may not know about Leonardo da Vinci, on the 500th anniversary of his death

A visitor takes a picture of the painting “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne” by Leonardo Da Vinci at the Louvre museum in Paris, France, Dec. 3, 2018.

This year marks the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death. Widely considered one of the greatest polymaths in human history, Leonardo was an inventor, artist, musician, architect, engineer, anatomist, botanist, geologist, historian and cartographer.

Though his artistic output was small, Leonardo’s impact was great, reflecting his deep knowledge of the body, his extensive studies of light and the human face, and his sfumato (Italian for “smoky”) technique, which allowed for incredibly lifelike images. Leonardo regarded artists as divine apprentices, writing “We, by our arts, may be called the grandsons of God.”

Related: Biographer Walter Isaacson, on Leonardo da Vinci’s art and science

Twenty-first-century scholars at MIT ranked him the sixth most influential person who ever lived. Like Rembrandt and Michelangelo, he is so renowned that he is known by only his first name. Yet despite his fame, there are things about Leonardo that many people today find surprising.

Shady parentage

Leonardo was born out of wedlock on April 15, 1452. His father, Piero, was a wealthy notary, and his mother, Caterina, was a local peasant girl. Although the circumstances of his birth would place Leonardo at a disadvantage in terms of education and inheritance, biographer Walter Isaacson regards it as a terrific stroke of luck. Rather than being expected to become a notary like his father, Leonardo was instead free to develop the full range of his genius. People surmise that it also imbued him with a special sense of urgency to establish his own identity and prove himself.

Physical beauty

Leonardo created some of the world’s most beautiful works of art, including the “Last Supper” and the “Mona Lisa.” In his own day, he was known as an exceptionally attractive person. One of Leonardo’s biographers describes him as a person of “outstanding physical beauty who displayed infinite grace in everything he did.” A contemporary described him as a “well proportioned, graceful, and good-looking man” who “wore a rose-pink tunic” and had “beautiful curling hair, carefully styled, which came down to the middle of his chest.” Leonardo is thought to have entered into long-term and possibly sexual relationships with two of his pupils, both artists in their own right.

From scraps to notebooks

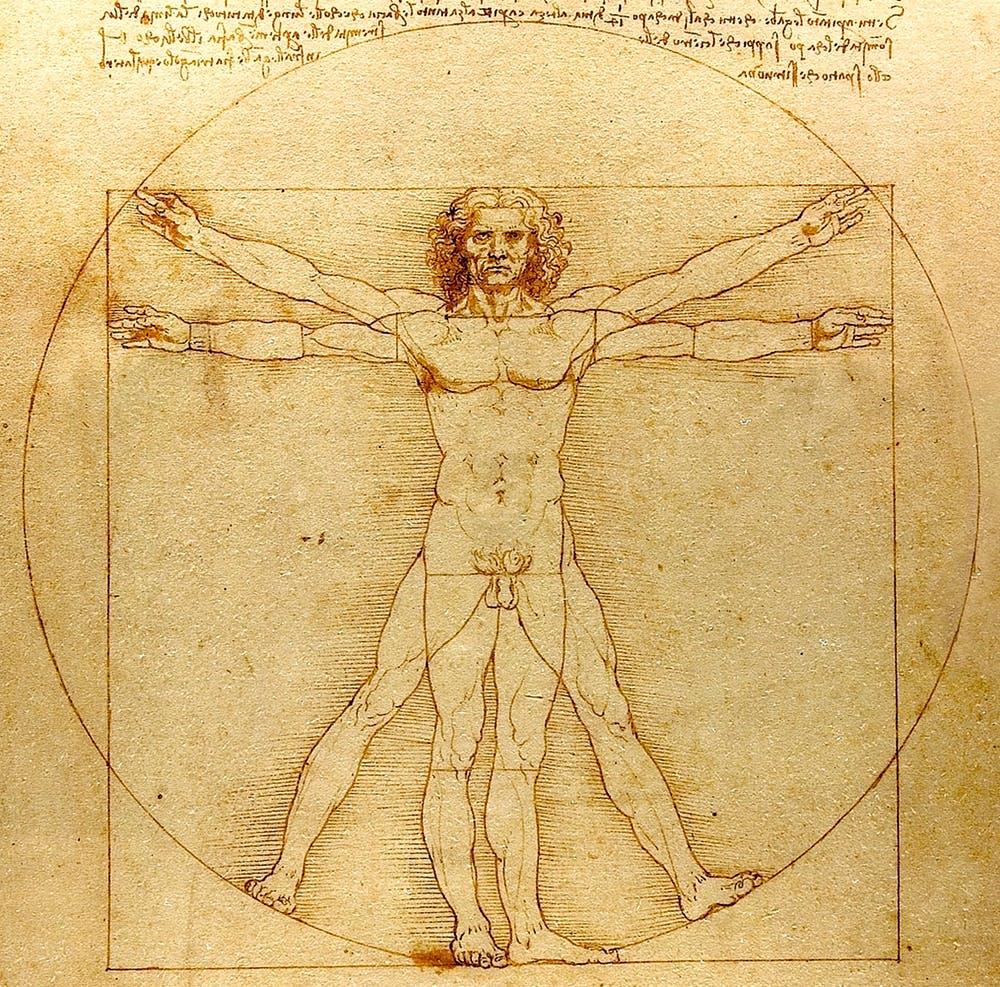

The paintings generally attributed to Leonardo number fewer than 20, while his notebooks contain over 7,000 pages. They’re the best source of knowledge about Leonardo, housed today in locations such as Windsor Castle, the Louvre and the Spanish National Library in Madrid. Their diverse content ranges across drawings — most famously, Vitruvian Man — notes of things he wanted to investigate, scientific and technical diagrams and shopping lists. They comprise perhaps the most remarkable monument to human curiosity and creativity ever produced by a single person. Yet when Leonardo penned them, they were just loose pieces of paper of different types and sizes. His friends bound them into “notebooks” only after his death.

Outsider’s education

As a result of his illegitimacy, Leonardo received a rather rudimentary formal education consisting primarily of business arithmetic. He never attended university and sometimes referred to himself as an “unlettered man.” Yet his lack of formal schooling also freed him from the constraints of tradition, helping to instill in him a determination to question authority and place greater reliance on his own experience than opinions expressed in books. As a result, he became a firsthand observer and experimenter, uninterested in serving as a mouthpiece for the classics.

Related: History sleuths track down Leonardo da Vinci’s living relatives

Prolific procrastinator

Although Leonardo’s mind was extraordinarily fertile, he was also an inveterate procrastinator and even quitter. He frequently took months or years to begin work on commissions, sometimes keeping patrons at bay with lofty pronouncements regarding his creative process. A giant equestrian statue for the duke of Milan, requiring 70 tons of bronze to cast, might have been his grandest work — if it had ever been completed. Yet a decade after the 1482 commission, Leonardo had produced only a clay model which was subsequently destroyed when invading French soldiers used it for target practice.

Rivalrous motivations

Leonardo’s life overlapped those of two other Renaissance giants — Michelangelo and Raphael — but it was Michelangelo who stoked an intense rivalry. The contrast between the two men could hardly have been sharper. Leonardo was elegant and evinced little interest in matters religious, while Michelangelo was deeply pious yet neglectful of his appearance and hygiene. Michelangelo created some of the greatest paintings in history, including the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and many considered his “David” the greatest sculpture ever produced, a triumph he lorded over his older rival.

Royal admirer

Soon after King Francis I of France captured Milan in 1516, Leonardo entered his service, spending the last years of his life in a house near the royal residence. When death came to Leonardo on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67, it is said that the king, who loved to listen to Leonardo talk so much that he was hardly ever apart from him, cradled his head as he breathed his last. Years later, reflecting on his friendship with the great man, King Francis said, “No man possessed such a knowledge of painting, sculpture, or architecture as Leonardo, but the same goes for philosophy. He was a great philosopher.”

Skyrocketing value

In November 2017, one of the paintings attributed to Leonardo, “Salvator Mundi” (“Savior of the World”), set the record for the most expensive painting ever sold, fetching US$450 million. Painted in oil on walnut in about 1500, it depicts Jesus offering a benediction with his right hand while holding a crystalline orb that appears to represent the cosmos in his left. The painting had suffered from neglect and poor restorations and was long assumed to be the work of one of Leonardo’s students, selling as recently as 2005 as part of the estate of a Baton Rouge businessman for less than $10,000. Its current whereabouts are unknown.

One of a kind, admired then and now

Just a half-century after Leonardo’s death, the biographer Vasari beautifully summed up his enduring significance:

Five hundred years after Leonardo’s death, these words still ring true.![]()

Richard Gunderman is a chancellor’s professor of medicine, liberal arts and philanthropy at Indiana University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.