Philippines security at risk over escalating tensions between US and China in South China Sea

Filipino activists and opposition leaders march to protest the presence of Chinese vessels in South China Sea at the Chinese Embassy in Makati City, Philippines, April 9, 2019.

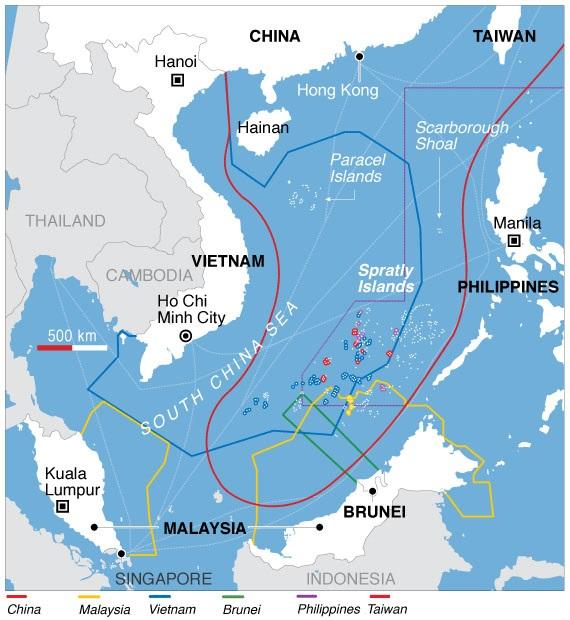

In the oil-rich South China Sea, where an estimated $5 trillion worth of global trade passes on a yearly basis, several neighboring nations including China, Philippines and Vietnam have each laid claims to long-disputed reefs, islands and waterways in the region.

As a larger nation with a stronger military, China claims the entirety of the Spratly and Paracel Islands — both lucrative for commercial fishing and potential underwater oil reserves. But the Philippines maintains control over several disputed islands within the Spratlys, according to an international agreement known as the Law of the Sea treaty.

Now, China is building an “island city” for military and strategic operations on Woody Islands in the Paracels, to the north of Spratlys — a move the United States deems illegal, insisting the South China Sea remains “international waters.”

Beijing’s recent moves have garnered global scrutiny and led to a show of US force aimed at countering Chinese expansion: In March, the US conducted its latest B-52 mission, one of several “freedom to navigate” missions in the Spratlys, but the Chinese view these patrols as a provocation, Reuters reported.

With escalating tensions between China and the US, security and sovereignty is a growing concern for the Philippines, which has remained close to its long-time ally, the US, while also courting China for new investment opportunities.

In February, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned that if China ever attacked the Philippines, it would “trigger mutual defense obligations” detailed in Article 4 of a Mutual Defense Treaty between the US and the Philippines, a former US colony.

The Philippines faces particular risk as the nearest neighbor to Spratly Islands’ Johnson South Reef, according to Anders Corr, publisher of the Journal of Political Risk. The reef is reportedly outfitted with Chinese anti-aircraft guns and a missile defense system, as suggested by 2016 photographs of the reef.

The Philippines claims Johnson South Reef actually belongs to it — its Palawan archipelago lies just 400 nautical kilometers to its east.

“…the militarization of the South China Sea in the Spratlys has been a particular burden for the Philippine fishermen. … The international legal regime and lack of enforcement have facilitated what are essentially fishing giveaways, especially to China.”

The Johnson South Reef is within the Philippines exclusive economic zone, or EEZ, and “the militarization of the South China Sea in the Spratlys has been a particular burden for the Philippine fishermen,” Corr said.

The Spratlys were mainly fished by Filipinos, but the area is now mostly fished by China, including its subsidized maritime militia. China gives privileged access to its own fishermen where it has control, whereas Filipino fishermen are consistently pushed out, Corr said.

“The international legal regime and lack of enforcement have facilitated what are essentially fishing giveaways, especially to China.”

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has taken a soft a stance on China in hopes of getting billions of dollars in investments promised by Chinese President Xi Jinping, but so far the island nation has seen little of it, according to The Guardian.

But in early April, Duterte spoke out against China’s “swarm” of coastguards and fishing vessels near the disputed Pag-asa Island, known as Thitu, also in the Spratlys.

“I will not plead or beg, but I am just telling you that lay off the Pag-asa because I have soldiers there. … If you touch it, that’s another story. Then I will tell my soldiers ‘prepare for suicide missions,’” Duterte said in a speech this month, The Guardian reported.

China, however, downplayed the presence of their ships near Pag-asa and assured cooperation.

“Beijing has spent the last decade being careful to avoid escalating the tensions to the level of kinetic force — both to avoid drawing the United States into a clash over the Philippines and to avoid the international fallout that would result from [China] using force against a smaller neighbor.”

“Beijing has spent the last decade being careful to avoid escalating the tensions to the level of kinetic force — both to avoid drawing the United States into a clash over the Philippines and to avoid the international fallout that would result from [China] using force against a smaller neighbor,” said Gregory Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative and fellow with the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Yet, in 2012, China’s standoff with the Philippines during the occupation of Scarborough Shoal, also part of the Spratlys, is telling. The Chinese had anchored eight fishing vessels in the waters by the shoal, an uninhabited rock located 120 nautical miles west of the Philippine island of Luzon. Filipino investigators tried to arrest the Chinese fishermen for illegally harvesting clams, corals and sharks, but Chinese ships blocked the arrest.

The shoal is now controlled by China, yet the Philippines claim the 58 square-mile rock based on historical usage, and the standoff sparked protests on both sides, as well as complaints from Filipino fishermen of ongoing Chinese harassment in the waters surrounding the shoal. Chinese coast guards have allegedly hit them with water cannons, raided their boats and snatched their best fish.

China’s rapid Spratly Islands build-up over the last five years and the resulting rise in the number of Chinese coast guards, military and paramilitary vessels throughout the South China Sea destabilize the status quo, Poling said, leaving smaller island nations like the Philippines vulnerable to possible Chinese military aggression — especially if the US continues to assert the right to navigate in these disputed waters.

A history of sea change

China’s history of military force in the region goes back at least 40 years.

In 1974, China wrestled the Paracel Islands from Vietnam and 14 years later, it took control of Vietnam’s Spratly Islands when it dominated nearby Johnson South Reef in a skirmish that killed 64 Vietnamese sailors in 1988.

Years later, those affected by the takeovers of Spratly and Paracel Islands continue to memorialize the historic struggle for territory.

“Vietnamese police routinely break up anti-China protests marking the anniversaries of the takeovers of the Spratly and Paracel Islands and detain demonstrators,” Radio Free Asia reported last year.

Last year, a small group of relatives and friends headed out on two high-speed boats from Da Nang, a city on Vietnam’s central coast, for waters near the Spratly Islands, to mark the 30th anniversary of the Johnson South Reef Skirmish.

The group held a vigil to remember the sailors killed in 1988 when Chinese and Vietnamese forces clashed over the right to annex the reef.

Power vacuums left by geopolitical shifts in the South China Sea have created the conditions for conflict, said Alexander Vuving, a professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Honolulu.

With the Paracels, Vietnam lost support from the US when the US withdrew militarily in 1973. Vietnam also lost support from the former Soviet Union when, in 1986, the USSR began to pursue rapprochement with China and curbed engagement with Vietnam.

“In both cases, China seized an opportunity when its aggressive actions would go with impunity to a large extent. China can be very aggressive, but its aggression is often well-calculated to exploit a favorable situation,” Vuving said.

“We’ve seen a number of cases of coercion or dangerous confrontations that could have easily escalated to violence,” Poling said, referring to Chinese aggression over land and waterway disputes.

Just last month, China allegedly caused a visiting Vietnamese fishing boat to sink.

Neighboring claimant countries of Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, Taiwan and Singapore have all been involved in ongoing maritime disputes in the region.

“Sooner or later that luck will run out — and someone will get rammed, fired upon or otherwise cause a situation to escalate into violence.”