In post-conflict Colombia, imprisoned ex-combatants help maintain a fragile peace

Adriana Cómbita, 27, has been leading conflict resolution workshops in prisons across Colombia. She’s on a mission to include prisoners in Colombia’s post-conflict peace building process.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

Last August, Adriana Cómbita found the perfect place for peacebuilding: a severely overcrowded and dilapidated prison in Barranquilla, a city on Colombia’s Caribbean coast.

Cómbita, 27, voluntarily visits prisons in Bogotá, her home town, and across the country to teach inmates that they are integral to real and long-lasting peace in Colombia.

Colombia’s post-conflict period began in 2016 after a 52-year-long war, when then-President Juan Manuel Santos signed a peace treaty with the FARC — formerly the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. The peace is fragile — the implementation of the treaty could take 20 years, and the country’s current president, Iván Duque, doesn’t support the accord as much as his predecessor did.

Related: Despite accord, peace in Colombia is tenuous as country heads to runoff election

Cómbita’s workshops exist within the context of Colombia’s new experimental judicial body, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, which encourages people charged with war crimes to confess everything in exchange for lighter sentences.

Cómbita says she refuses to wait and see what will happen to peace in Colombia. Duque and the FARC — now a political party — aren’t the only ones responsible for its success, she says.

“It depends precisely on us to give tools to inmates so they can become peace builders within themselves,” Cómbita insists. “Then they recreate [peace] with each other, with their families and with society.”

Cómbita works with inmates as a volunteer through Acción Interna, a foundation well known within the prison system that helps Cómbita set up conflict resolution and leadership workshops grounded in storytelling and creative expression.

‘I had a hardened heart’

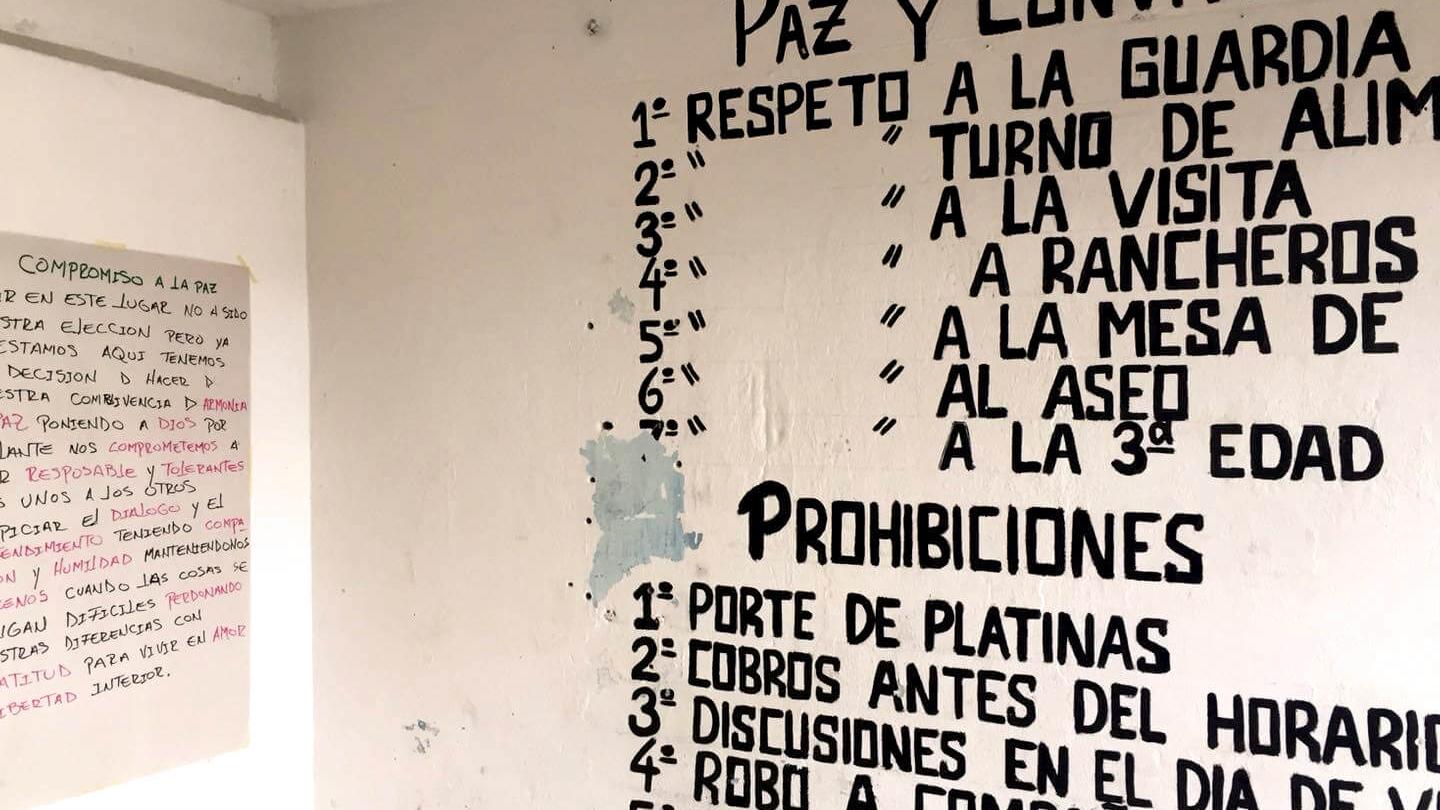

Guards inspect visitors’ bags outside the men-only penitentiary known as El Bosque, and inside, without air conditioning, the rancid odor of filth permeates the stagnant air. Prisoners’ clothes hang to dry through the bars on each floor, adding bursts of color to the drab interior. Near the entrance, inmates in a dark cell shout out to men in other cells, swapping stories, creating echoes all day long.

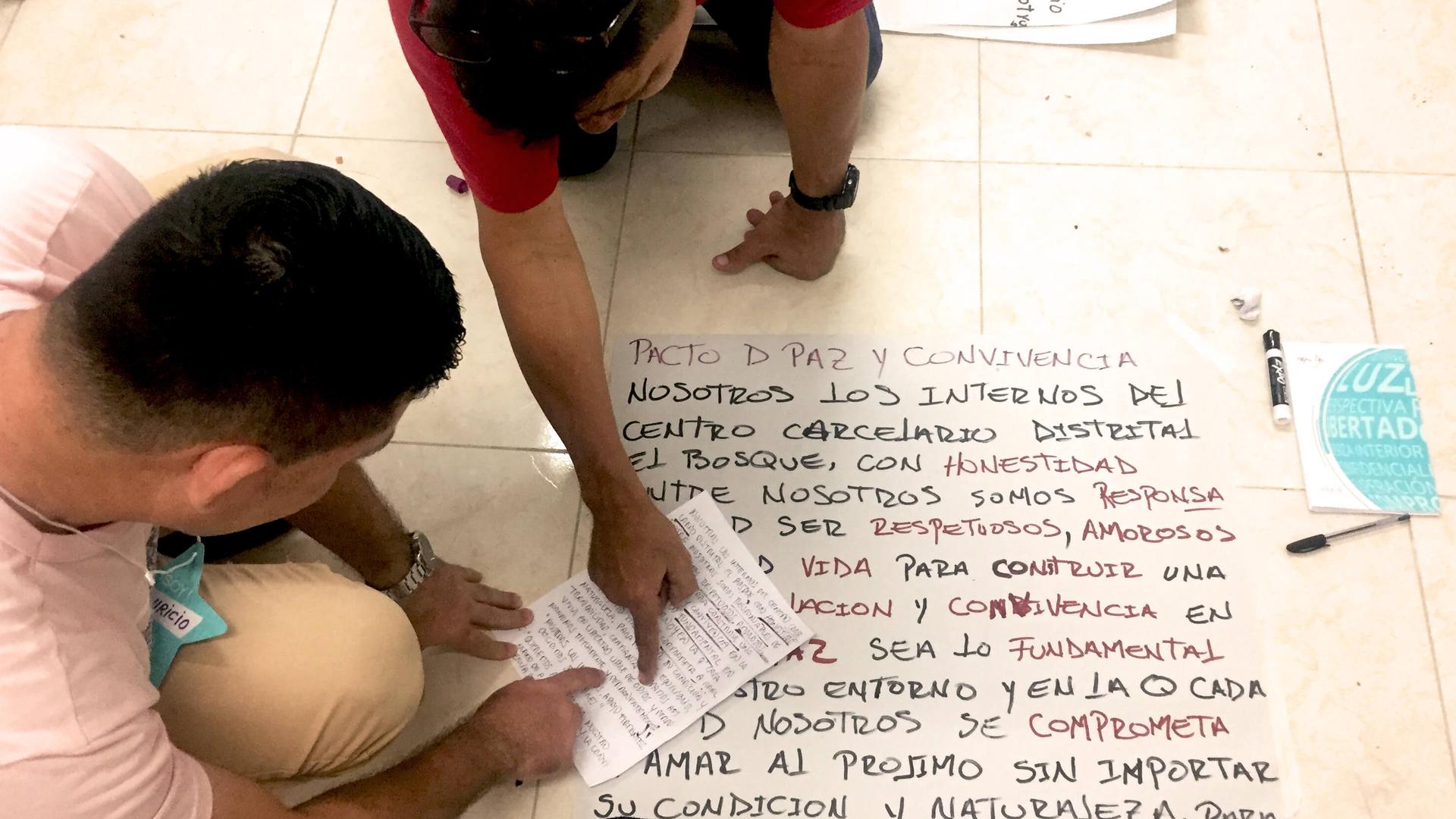

Cómbita conducts her workshops in a surprisingly quiet room on the ground floor, where nearly 50 inmates await, sitting on plastic chairs. She usually visits a new prison once a month and spends two to four days with prisoners, always on behalf of Acción Interna.

The workshop opens with a discussion on the pitfalls of anger and violence. Inmates in Cómbita’s workshops spend much of their time looking inward and write essays about their families and communities. Later, workshop members stand with a microphone in hand to share the stories of their first names. David, for example, says his Christian mom named him after the ancient King of Israel. Another man, Oscar, says his parents named him after the Hollywood film award. This gets a roar of laughter.

Midway through the workshop, Cómbita tells inmates how biases and prejudices can blow up, literally like a “bomba,” or a bomb, she tells them in Spanish. She asks them to give an example of how assumptions can lead to fights in prison.

One inmate — who asked to go by the name Matias — stands up to say that he and another prisoner in the room nearly got into a fight over some rumors, but instead they talked it out. Suddenly, he leans over and gives the guy a hug.

Matias fought as a paramilitary soldier during Colombia’s war.

Paramilitaries were right-wing groups that mostly fought turf battles against the left-wing FARC, and in the process victimized civilian Colombians. According to Colombia’s National Center for Historical Memory, paramilitaries killed almost 95,000 people during the conflict — some 60,000 more than were killed by FARC.

Matias isn’t his real name, he uses an alias for protection. If other ex-paramilitaries in this prison find out he’s “talking,” he says, or speaking to a reporter, they would kill him.

“If you say you’re one of the demobilized, people look at you over their shoulder like you’re the worst, without knowing you got into this conflict for lack of opportunities.”

Matias fought with the notorious Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia — or United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia. The US government labeled the AUC a foreign terrorist organization in 2001, like the FARC in 1997.

“The AUC has carried out numerous acts of terrorism, including the massacre of hundreds of civilians, the forced displacement of entire villages, and the kidnapping of political figures to force recognition of AUC demands,” wrote then-Secretary of State Colin Powell in September 2001.

More than 30,000 paramilitary fighters demobilized by 2006, after a peace treaty between Colombia’s government and the AUC.

“If you say you’re one of the demobilized, people look at you over their shoulder like you’re the worst, without knowing you got into this conflict for lack of opportunities,” Matias says.

He remebers the kind of guy he used to be. “I could never say ‘I love you,’” he says. “I had a hardened heart. But I’ve done a lot of these workshops in prison. They teach you about values and principles. So you start feeling emotions.” Now a hug from his son or grandson makes him tear up.

Incentivizing peace

Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace, known as the JEP, was established through the 2016 peace accord and mainly focuses on trying ex-FARC insurgents — especially those who had higher levels of command. Most of the FARC insurgents who demobilized under the peace treaty received amnesty and are transitioning into society.

Related: Former FARC fighters turn a camp into a tourist attraction

This temporary court can also bring former paramilitary members to trial, but former lower-level fighters, like Matias, are often left out of this process because paramilitaries were already processed through a different justice system.

“I think one of the good things [about the] design of this system is that it incentivizes the recognition of responsibility,” says Juanita Goebertus, a Green Party member of Colombia’s Congress representing Bogotá. Goebertus is also active in Colombia’s peace process.

Say an ex-FARC fighter charged with a war crime confesses to the crime right away. This person’s punishment would focus on forms of justice that match the severity of their crimes, yet lean toward constructive rehabilitation. Such punishments might include removing landmines, searching for people who were disappeared or helping to construct bridges or other infrastructure. Sentences last between five to eight years, depending on the severity of the crime. During this time, the former combatant is restricted to a region determined by the JEP. The idea is to place former combatants in the position of rebuilding communities devastated by the war.

“I think one of the good things [about the] design of this system is that it incentivizes the recognition of responsibility.”

Sometimes, victims who are owed reparations may weigh in on whether they think the restorative punishment seems adequate.

If a former fighter, for example, doesn’t confess right away, he or she will receive a punishment that includes a jail sentence between five and eight years, plus community service. Only those who refuse to admit to their role in a crime face straight prison time of up to 20 years.

Colombia’s war left more than 200,000 people dead, and more than 7 million internally displaced persons. “You can’t treat abnormality with normality,” says Daniel Marín, a researcher at Dejusticia, an advocacy and research organization in Bogotá that promotes human rights. This is one reason he says Colombia needed a new justice system for these specific cases, rather than to rely on a traditional court.

“I’m highly optimistic in a certain way,” Marín continues. “I think that the special jurisdiction for peace made good work opening some huge cases that are very significant for Colombian society. For instance, [cases on] kidnappings and extrajudicial killings by the armed forces.”

These have deeply wounded Colombians over the decades, he adds. “The special jurisdiction for peace can be a real scenario for justice, but let’s see. It’s very early.”

Under the peace agreement, the JEP tribunal will have 15 years to finish its work with all pending cases, though magistrates may ask for a five-year extension. The court can only request a 20-year total at the very most.

Related: In Colombia, President-elect Duque faces challenges on peace, economy

A new generation of peacemakers

Cómbita started working with prisoners after completing a fellowship called Generation Change with the United States Institute of Peace, a US government institution that funds peace initiatives in post-conflict nations like Colombia and Afghanistan, and across Africa and the Middle East. The US has spent billions of dollars on helping Colombia combat drug production and drug-trafficking groups.

“We did a call for applications for the fellowship program and we received over 1,000 applications for a cohort of 22 people,” says Tonis Montes, a USIP program specialist focused on Colombia. “That speaks to the activity we’ve seen in Colombia from young organizers and activists after the plebiscite failed,” referring to the 2016 vote before the peace treaty was signed, in which a slim majority of Colombians rejected the government’s FARC peace deal.

Angry over this setback, thousands of Colombians, many of them university students, marched in nationwide protests and set up a peace camp in the capital. Later, after changes to the original accord — including requiring that the FARC declare its assets to compensate victims and providing more specifics on the system of penalties for those found guilty of crimes — Colombia’s Congress approved the treaty.

Cómbita says she identifies as a part of Colombia’s youth tired of the half-century-long war. Living in the capital city of Bogotá, Cómbita never experienced the war directly, but her father was intimidated during the conflict — a threat she can’t elaborate on out of concerns for her family’s safety.

The USIP chose Cómbita out of a large pool of applicants, and after she finishing the fellowship in 2017, she developed her workshops with Acción Interna.

Related: Can Pope Francis get Colombia to reconcile after decades of war?

One of these workshops proved especially memorable — at the Villahermosa jail in Cali, the capital of Colombia’s Valle del Cauca department, southwest of Bogotá.

“It’s been one of the most unforgettable experiences of my life,” Cómbita says. Some of the prisoners were ex-FARC insurgents, others were former paramilitaries and ex-combatants with another group, the National Liberation Army, or ELN, which is still armed and operating in much of Colombia.

She instructed the prisoners to draw a “rio de la vida,” or “river of life,” and place a life float to represent a lifeline they’ve gotten along the way. They all drew a float of the 2016 peace accord.

“They told me that that was the hope for them to take a different course in their lives,” Cómbita says.

For his own part in the war as a paramilitary fighter, Matias says he, too, has taken a different course.

“I’ve felt remorseful a thousand times, of all the things I participated in,” Matias says. “If only I could ask the victims to forgive me for all those things. We’re humans, we commit mistakes, but the important thing is for a person to change.”