The long, bipartisan history of dealing with immigrants harshly

A migrant camp in Weslaco, Texas, in February 1939. A Library of Congress caption reads: “… The charge for camping in tents is about fifty cents per week, including water, which in some cases must be carried four city blocks. Privies are tin, very bad condition. Garbage is collected only once a week, with large dumps of decaying fruits and vegetables scattered among the camps. Some of the white migrants in this camp were very suspicious of governmental activity, due to the use by south Texas newspapers of the term ‘concentration camps’ referring to FSA (Farm Security Administration) camps.”

From the Trump administration’s Muslim travel ban to its family separation policy, many Americans object to the White House’s hardline immigration policies as a historical aberration out of sync with US values.

Having explored the evolution of these policies and their consequences as both a practitioner of immigration law and scholar of US-Latin American relations, I disagree.

Rather than marking a stark departure, I see President Donald Trump’s approach as ramping up and expanding the US government’s longstanding efforts to punish undocumented immigrants.

His record on immigration does appear to be more inhumane and cruel than that of his predecessors. But his legacy will not, I’m afraid, be un-American.

Racism, recession and war

Following a long history of more open and welcoming immigration policies, in the first half of the 20th-century US attitudes toward immigration became increasingly restrictionist. Racism against immigrants of color drove immigration legislation, especially during economic downturns and political turmoil.

Beginning in 1924, the government set national immigration quotas. Due to a belief in eugenics, a pseudo-science claiming that Nordic and Anglo-Saxon races are superior to all others, the authorities effectively cut off legal immigration from all but a few Western European nations.

Lawmakers claimed it was for the sake of preserving and improving upon the nation’s ethno-linguistic heritage as recorded in the 1890 census. The count excluded most African Americans and all Chinese Americans.

Related: Can a ‘merit-based’ immigration system work in the US?

There were no quotas for immigrants from neighboring countries, however. And so then, as now, Mexican migrants filled industrial and agricultural labor shortages, especially across the Southwest.

But once the Great Depression began and unemployment soared, President Herbert Hoover bowed to popular pressure to preserve “American jobs for real Americans” and approved the large-scale deportation of Mexican workers and their families.

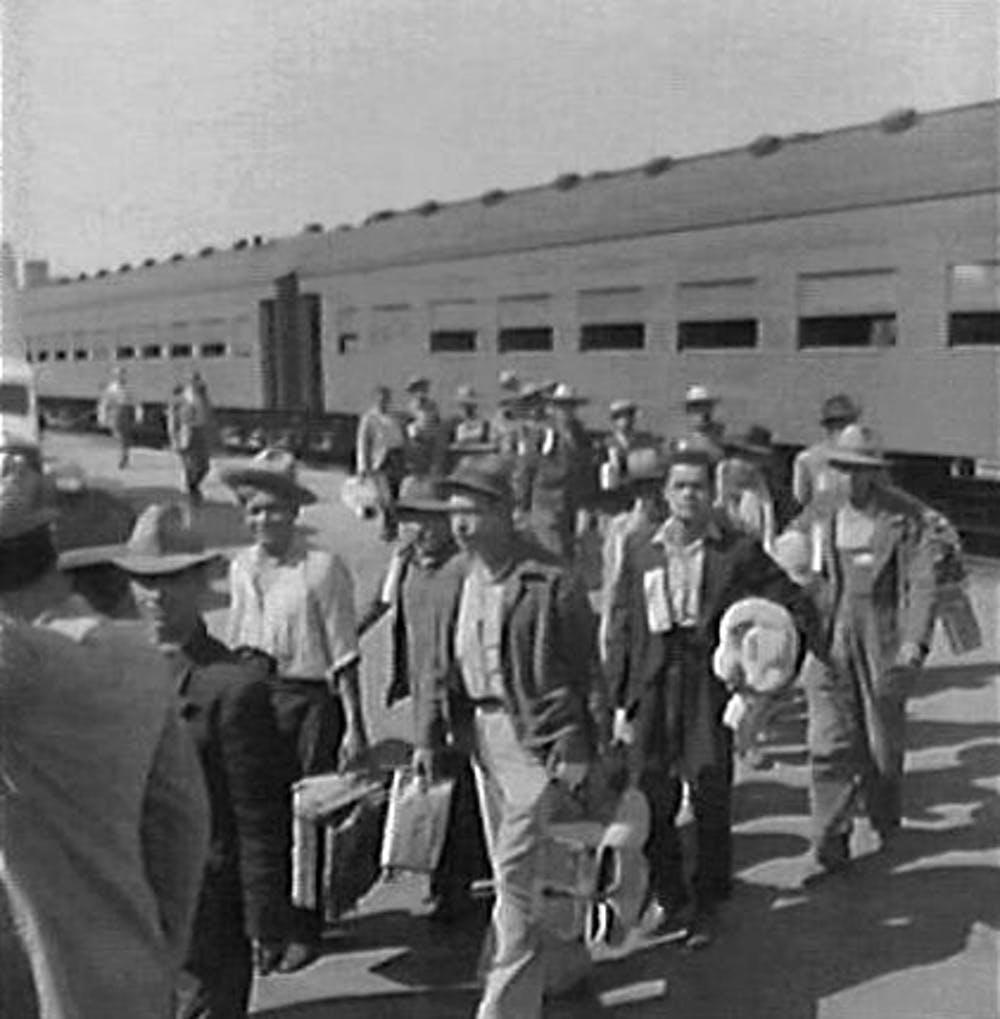

Largely carried out by local law enforcement between 1929 and 1936, the deportation dragnets rounded up hundreds of thousands of people of Mexican descent —many of them US-born citizens — and forced them onto trains bound for Mexico.

Related: Another time in history that the US created travel bans — against Italians

The advent of World War II reignited longstanding anti-Japanese attitudes. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration forced nearly 120,000 people of Japanese descent — most of them US citizens — into remote internment camps between 1942 and 1945. His administration also deported thousands of Japanese Americans who had renounced their citizenship under duress. And the government turned away at least 200,000 Jewish refugees who were fleeing the Nazis despite the quotas for their countries not being filled.

World War II also revived the US economy, suddenly creating labor shortages in jobs left by those who had joined the war effort. Looking south for a fix, lawmakers established the Bracero program. It encouraged and regulated the flow of Mexican migrants primarily employed as farm workers from 1942 until 1965 — when a landmark immigration law abolished national quotas.

Many employers preferred to hire undocumented workers to avoid the Bracero program’s bureaucracy and wage restrictions. In 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower initiated “Operation Wetback” to force hundreds of thousands of low-paid farm workers to leave the country.

Like Hoover’s deportation spree, officials made little effort to differentiate between the US citizens and noncitizens who got rounded up and deported. Historians have found that innumerable US-born people were again among the hundreds of thousands supposedly repatriated to Mexico.

Reagan, asylum and amnesty

Since 2014, growing numbers of Central Americans have arrived at the US-Mexico border seeking asylum. The Trump administration has gone out of its way to discourage these migrants by changing eligibility criteria, application procedures and detention practices.

Large numbers of Central Americans first began to arrive in the US in the 1980s — in many cases fleeing US-backed brutality. Rather than acknowledge its allies’ human rights abuses, the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush labeled these asylum-seekers “economic migrants.” Less than 3% were granted asylum, a fraction of the approval rate for refugees fleeing communist regimes in Eastern Europe and oppression in Iran and Afghanistan.

Even so, Reagan also demonstrated generosity toward undocumented migrants. His administration’s 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act provided amnesty for over 3 million undocumented immigrants — the vast majority of them from Mexico and Central America — letting them become permanent legal residents.

The 1986 law also took major steps to toughen border security to deter future undocumented migration. Combining legalization with deterrence, Reagan hoped, would fix the nation’s immigration system once and for all.

However, the law created no means of regulating future migration to the US. Economic turmoil in Mexico during the 1980s and early 1990s — especially following the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement — pushed more migrants north. As a result, millions more people ended up living and working in the US with few prospects for gaining legal status.

Clinton’s legacy

Aside from the complementary measures adopted during the first Bush presidency, no president since Reagan has signed legislation for another expansive amnesty for the undocumented. With few exceptions, immigration policies have become increasingly punitive with the passage of time.

More than any other president, Bill Clinton paved the way for Trump’s plans to deport millions of undocumented families, terrify others into voluntarily departing and slash legal migration. During his 1996 reelection campaign, Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, one of the most draconian and far-reaching pieces of anti-immigration legislation in US history.

The 1996 law eroded due process for many migrants seeking asylum. It created a program that enlists local law enforcement agencies into immigration enforcement. Critics of the program say it drives a wedge between the police and immigrant communities, interfering with law enforcement.

Following the law’s passage, deportation numbers soared, setting new records for the numbers of immigrants detained during the Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama administrations.

‘Deporter-in-Chief’

Even as they inherited what immigrant rights advocates call a growing “deportation machine,” both George W. Bush and Barack Obama attempted to soften immigration policies.

The second President Bush accepted record numbers of refugees. Obama created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program to shield thousands of undocumented migrants who entered the country as children from deportation.

Yet, immigrants’ rights activists dubbed Obama “deporter in chief,” for having deported more immigrants than any president in history. So far, he retains this title because his administration deported more migrants per year than Trump.

Trump’s wider scope

Trump inherited an immigration system that left millions of undocumented people with few rights and a militarized southern border. But Trump has sharpened and hypercharged punitive immigration policies. By calling undocumented immigrants “animals” and conjuring images of vermin who “infest” this country, Trump has invoked racist rhetoric toward migrants that no other president since the civil rights movement has used, at least not in public.

Related: US visa denials skyrocket under ‘back door’ public charge rule change

Beyond the humanitarian catastrophe unfolding at the southern border, Trump axed Obama’s emphasis on deporting immigrants with serious criminal records or who posed a national security threat. Instead, he has targeted people other presidents tried to protect, such as immigrant children, immigrants with no criminal record, those who fled major natural disasters, and US citizens with undocumented loved ones.

The Trump administration has also widened the scope of enforcement actions to include some newcomers who had already become US citizens.

And despite Trump’s symbolic celebrations of the US military, the government is apparently stepping up the deportation of noncitizen veterans and moving to deport some active-duty service members along with their families.![]()

Anthony W. Fontes is an assistant professor of human security at the American University School of International Service.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.