Tough commute? Try crossing the US-Mexico border to go to school

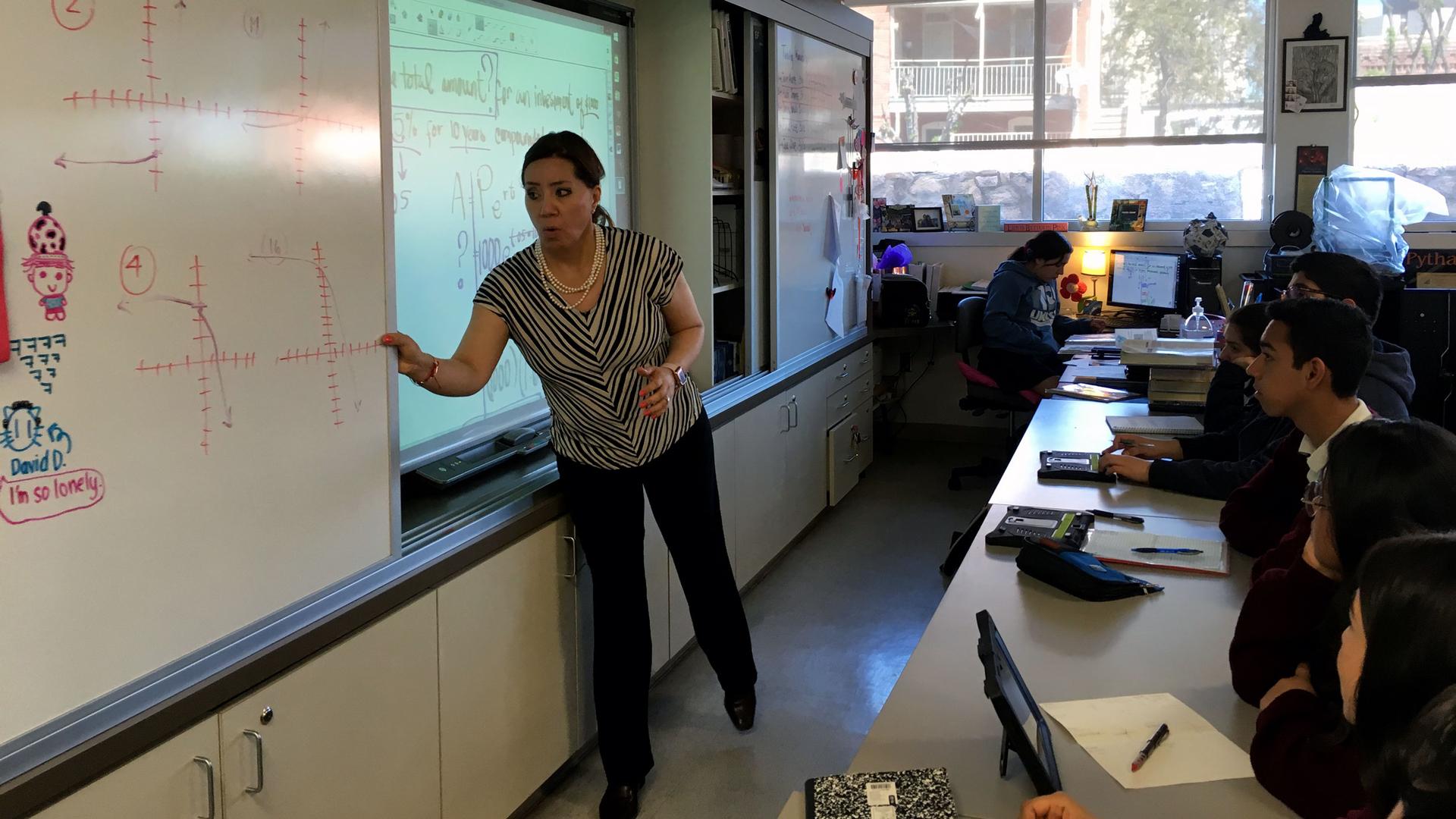

Students at the Lydia Patterson Institute in El Paso, Texas, listen to their teacher. More than 70 percent of the students in the private school travel over the US-Mexico border to attend classes.

There’s a five-mile-long line of trucks amassed at the border between Ciudad Juárez and El Paso, after the Trump administration moved federal agents away from ports of entry to other immigration duties. The delays can cause gridlocks lasting up to 12 hours and convince some business owners to consider moving goods via air freight to avoid the lines.

But the truckers aren’t the only ones waiting in lines at the border.

High school senior Melissa Sánchez starts her day at 5:30 a.m., even though class won’t start for hours.

Sánchez lives in Ciudad Juárez and goes to school across the border in El Paso.

Related: This immigration bill won’t pass but is still a ‘major win’

“I leave my house, like, at 6:20, 6:30,” Sánchez says. “Then we get into the line to cross the border and we wait like an hour or an hour and a half, usually. But nowadays, since things got a little bit crazy, we’re waiting two to three hours, so I need to wake up more early.”

Many migrants are also lined up, waiting, on the same walkway Sánchez takes to school.

“I think it’s really sad to see them just sitting and waiting for some kind of miracle to happen to their lives,” she says. “Because I have the privilege to go to school, to have a family. I see those poor kids. They didn’t have a place to stay, and that’s the only thing that kind of runs through my mind.”

Sánchez walks with her mother over the pedestrian crossing and sees migrants waiting, but she hasn’t spoken to them. There is little interaction.

Sánchez’s school, the Lydia Patterson Institute, is a private Methodist School. It’s also bilingual and some 70 percent of it’s 350 students come from Mexico every day.

Socorro de Anda is the president of the school and has worked there for more than 30 years. The school itself opened in 1913.

“Generations of students have gone through here,” de Anda says. “We’re here to create leaders for both sides of the border.”

Sánchez says she’s wanted to study in the US ever since she was a kid.

Related: Why are so many migrant families arriving at the southern US border?

“My dream since I was little, I wanted to come to college here,” she says. “And also that I wanted to get to know more people, more cities, more countries.

She got a full scholarship, like a lot of students at the school.

But now, the school has been preparing for possible border closures, even if they’re temporary. De Anda met with the students this week.

“[I] told them not to worry about it,” she says. “I want you to worry about your school work.”

They’ve also got a back-up plan, just in case.

Related: How Ciudad Juarez is bracing for more migrants under US ‘remain in Mexico’ policy

“We are ready to be able to transmit our classes via computers if need be, and they can receive their classes there with their own computers or their tablets or even their cell phones. We’ve got a plan.”

De Anda says doesn’t think she’ll need the back-up plan, but she’s anxious. She says the possible border closure keeps her up at night.

“I cannot see the border closing for too long a period of time,” she says. “Frankly, I cannot. It would be disastrous to the state of Texas and it would be disastrous to the whole country.

And despite the longer lines, de Anda says the students are making it to school on time. Many of them are doing it by getting up even earlier, just like Sánchez.

“It’s really hard, to take a step up and say I need to do this,” she says.

Sánchez used to sleep seven hours a night. Now, with the longer lines, it’s more like five.