A teen scientist helped me discover tons of golf balls polluting the ocean

A harbor seal investigates a member of the golf ball recovery team.

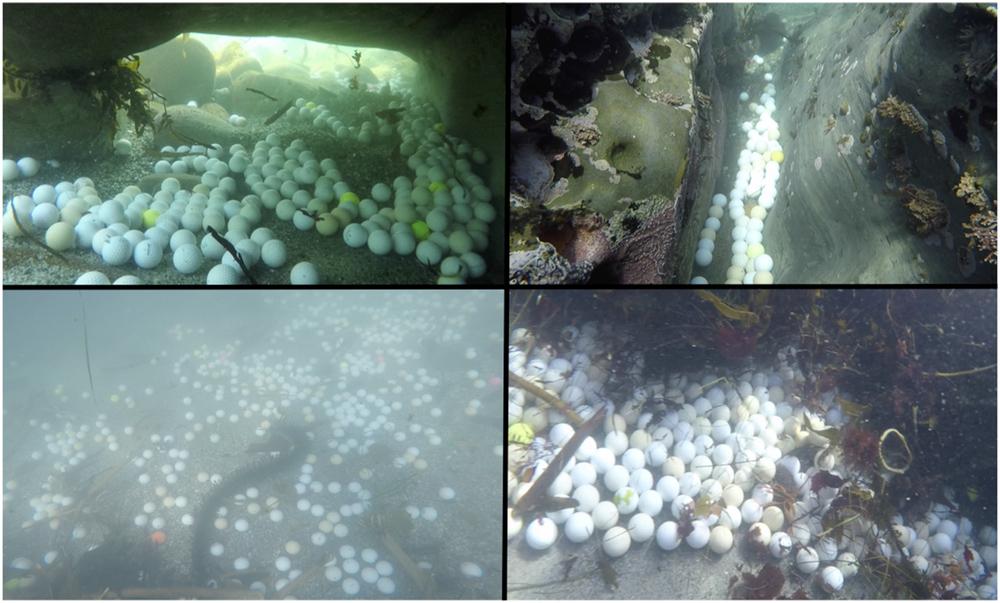

Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans has become a global environmental crisis. Many people have seen images that seem to capture it, such as beaches carpeted with plastic trash or a seahorse gripping a cotton swab with its tail.

As a scientist researching marine plastic pollution, I thought I had seen a lot. Then, early in 2017, I heard from Alex Weber, a junior at Carmel High School in California.

Alex emailed me after reading my scientific work, which caught my eye, since very few high schoolers spend their time reading scientific articles. She was looking for guidance on an unusual environmental problem. While snorkeling in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary near the town of Carmel-by-the-Sea, Alex and her friend Jack Johnston had repeatedly come across large numbers of golf balls on the ocean floor.

As environmentally conscious teens, they started removing golf balls from the water, one by one. By the time Alex contacted me, they had retrieved over 10,000 golf balls — more than half a ton.

Golf balls sink, so they don’t become eyesores for future golfers and beachgoers. As a result, this issue had gone largely unnoticed. But Alex had stumbled across something big: a point source of marine debris — one that comes from a single, identifiable place — polluting federally protected waters. Our newly published study details the scope of this unexpected marine pollutant and some ways in which it could affect marine life.

Cleaning up the mess

Alex wanted to create a lasting solution to this problem. I told her that the way to do it was to meticulously plan and systematically record all future golf ball collections. Our goal was to produce a peer-reviewed scientific paper documenting the scope of the problem, and to propose a plan of action for golf courses to address it.

Alex, her friends and her father paddled, dove, heaved and hauled. By mid-2018 the results were startling: They had collected nearly 40,000 golf balls from three sites near coastal golf courses: Cypress Point, Pebble Beach and the Carmel River Mouth. And following Alex’s encouragement, Pebble Beach employees started to retrieve golf balls from beaches next to their course, amassing more than 10,000 additional balls.

In total, we collected 50,681 golf balls from the shoreline and shallow waters. This represented roughly 2.5 tons of debris — approximately the weight of a pickup truck. By multiplying the average number of balls lost per round played (1-3) and the average number of rounds played annually at Pebble Beach, we estimated that patrons at these popular courses may lose over 100,000 balls per year to the surrounding environment.

The toxicity of golf balls

Modern golf balls are made of a polyurethane elastomer shell and a synthetic rubber core. Manufacturers add zinc oxide, zinc acrylate and benzoyl peroxide to the solid core for flexibility and durability. These substances are also acutely toxic to marine life.

When golf balls are hit into the ocean, they immediately sink to the bottom. No ill effects on local wildlife have been documented to date from exposure to golf balls. But as the balls degrade and fragment at sea, they may leach chemicals and microplastics into the water or sediments. Moreover, if the balls break into small fragments, fish, birds or other animals could ingest them.

The majority of the balls we collected showed only light wear. Some could even have been resold and played. However, others were severely degraded and fragmented by the persistent mechanical action of breaking waves and unremitting swell in the dynamic intertidal and nearshore environments. We estimated that over 60 pounds of irrecoverable microplastic had been shed from the balls we collected.

Game-changer

Thanks to Alex Weber, we now know that golf balls erode at sea over time, producing dangerous microplastics. Recovering the balls soon after they are hit into the ocean is one way to mitigate their impacts. Initially, golf course managers were surprised by our findings, but now they are working with the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary to address the problem.

Alex is also working with managers at the sanctuary to develop cleanup procedures that can prevent golf ball pollution in these waters from ever reaching these levels again. Although her study was local, her findings are worrisome for other regions with coastal golf courses. Nonetheless, they send a positive message: If a high school student can accomplish this much through relentless hard work and dedication, anyone can.![]()

Matthew Savoca, Postdoctoral researcher, Stanford University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.