Amid 1619 anniversary, Virginia grapples with history of slavery in America

Free Egunfemi, founder of Untold RVA, at the African Burial Ground in Richmond, Virginia.

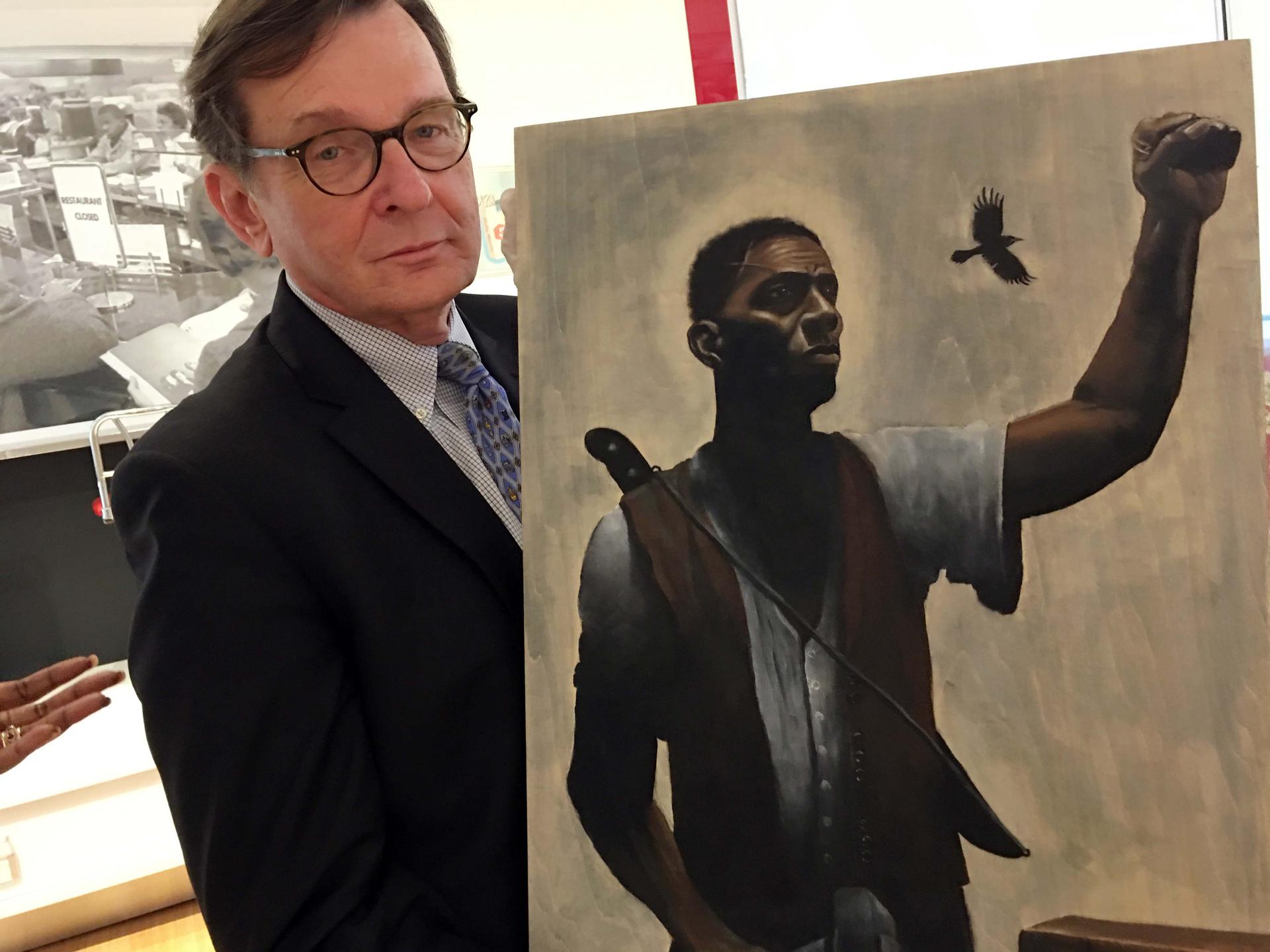

At the Valentine gallery in Richmond, Virginia, Free Egunfemi shows me a portrait that will be unveiled later this year.

“So this is Gabriel,” says Egunfemi, independent historian and founder of Untold RVA, an organization devoted to sharing Richmond’s untold stories.

She tells me Gabriel was an enslaved man who tried to hold the governor of Virginia hostage in 1800 to bargain for freedom for slaves. No one knows what he looked like. Egunfemi commissioned the painting.

“What’s so interesting about this is that we used a pattern for his visage based on his descendants,” she says.

Related: Pirates brought enslaved Africans to Virginia’s shores. Where, exactly, is debatable.

That’s the closest they can get without any contemporary description of Gabriel. The only reason we know about him is because he broke the law. For most of the millions of other enslaved people living in the US at the time, we know nothing. There’s no documentation at all. And that’s a problem when you’re telling American history.

In official history, Gabriel’s rebellion failed. Someone reported the plot. Gabriel and his conspirators were discovered and they were hanged. In Egunfemi’s re-telling of history, Gabriel is a hero — one of many who have gone mostly unremembered.

“Those are the narratives that were deliberately submerged,” she says. “Those are the stories nobody wanted to tell.”

Such stories begin in the 1600s, when the first enslaved Africans arrived in the English colonies. White Virginians used African slavery to rapidly expand the tobacco industry. That quickly made Virginia the most powerful colony in the New World. Slaves like Gabriel fought back, and white Virginians created a system of laws to oppress them — a system that other colonies, then states, used as a model.

Karen Sherry is a museum curator putting together a special exhibit that will detail the history of enslaved Africans. She started the job in 2017, just weeks after a violent “Unite the Right” protest in Charlottesville, an hour and a half away. Heather Heyer, an anti-hate protester, was killed by a white supremacist during the rally.

“Those events have really crystallized for me how much race is still an issue in American society,” says Sherry, who works for the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, the modern version of the Virginia Historical Society.

She shows me a pristine sheet of paper — a letter to the governor, dated 1690, and reads from it: “May it please your excellency. Whereas there was a rumor of an evil and desperate design contrived by the negroes …” It’s an affidavit by five slave owners complaining about rebellious enslaved Africans.

“We very rarely find any kind of artifactual item related to black people,” she says. “What we have are documents that were written by white people, generally people in power.”

The job of filling in the blanks has been left to historians and curators, professions where African Americans are still underrepresented.

“I have to acknowledge as a representative of this institution, historically we haven’t always been very inclusive in the kinds of stories we tell about American history. But that’s something that’s changing, not just at our institution, but at many institutions,” Sherry says.

The 1619 anniversary is proving to be something of a catalyst. For the first time in 400 years, Virginia is marking the arrival of the first enslaved Africans along with other significant events of 1619, including the arrival of the first women in the colonies and the establishment of the first government. It’s part of a year-long tourism push called American Evolution. Kathy Spangler is the director.

“If you can imagine that we would be having the seeds of democracy at the same time that the seeds of slavery were being forged,” she says. “Frommer’s [Travel Guides] has put Virginia on its top places to go in 2019 because of this commemoration.”

Spangler says there were many committees and roundtables to make sure diverse voices were represented in the planning for American Evolution events. And Spangler talked to the experts.

“We looked to the best institutions in Virginia,” she says. “We went to those who are the keepers of this history.”

“You’re not in there doing your own work, and no one’s paying you, and everybody up in there is getting paid but you,” Egunfemi says.

Egunfemi drives me around, pointing out hang out spots from her childhood. She tells me about studying violin at Julliard, raising three daughters as a single mom and winning acclaim for her work as a vegan chef.

In 2013, then Richmond Mayor Dwight C. Jones announced plans to build a baseball stadium on a site called the African Burial Ground.

Egunfemi takes me there. It’s a grassy field just east of downtown, sitting under railroad tracks and interstate 95. It used to be a parking lot.

“This area was called Shockoe Bottom,” she says.

In the decades before the Civil War, this was second-busiest slave-trading site in the country.

“[Enslaved Africans] would come on ships right on the edge of the water,” Egunfemi says. “Then [slave traders] would march them in the middle of the night because the wealthy Richmonders did not want to see people that have just come from a three-month journey from Africa. Barefoot. The smell was unbearable.”

Solomon Northup, the enslaved man whose life was portrayed in the movie “12 Years a Slave,” was supposedly held here after he was kidnapped. And, Egunfemi tells me, this is also where Gabriel was hanged. Egunfemi’s put up posters all around here with a phone number people can call to hear her history of this place. The signs are tattered. Some look like they were intentionally torn off.

History needs to be corrected, Egunfemi tells me, because it’s been told through the eyes of oppressors. She says it almost seems like America’s gotten over its involvement in the slave trade, and racism isn’t an issue anymore. Egunfemi thinks Virginia’s official commemoration of the 1619 arrival is just history for history’s sake, when it could be so much more if it were connected to what African Americans experience today.

“We can’t be separated from it. We won’t be separated from it,” Egunfemi says. “And if they wish to separate, there’s going to be two different tales.”

A black version of history, she says, and a white one. Egunfemi says neither will be the full story because these stories are inexorably entwined.

“When we were running, we weren’t hiding in black-owned barns. We weren’t feeding ourselves,” she says. “We had allies that owned the wagons and all the things that we needed to escape from enslavement.”

And, Egunfemi says, it will take many more alliances to repair the history of the last 400 years.