Venezuelan oil fueled the rise and fall of Nicaragua’s Ortega regime

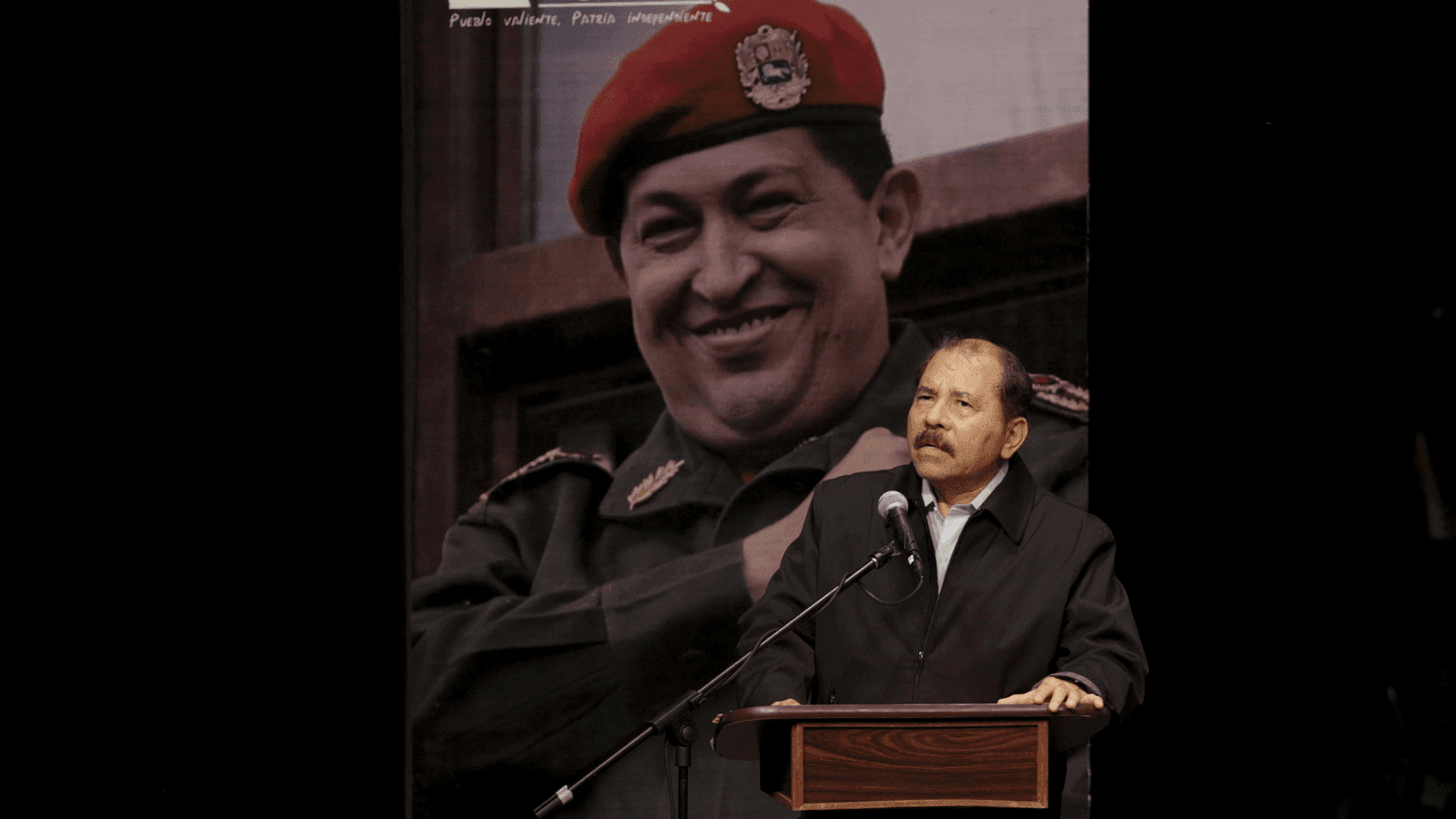

Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez was a major financier of Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, seen here at a 2016 commemoration on the third anniversary of the socialist leader’s death.

The downfall of Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega has been dizzyingly fast.

In January 2018, he had the highest approval rating of any Central American president, at 54 percent. Today, Nicaraguans are calling for Ortega’s resignation.

Ortega, a former Sandinista rebel who previously ruled Nicaragua in the 1980s, first showed signs of weakness in early April, when students protested his mismanagement of a massive forest fire in Nicaragua’s biggest nature reserve.

By April 19, hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguans, including former Ortega supporters, joined the demonstrations after his government rammed through an unpopular social security reform.

Since then, police officers and pro-government forces have killed more than 450 protesters and injured at least 2,500.

In an echo of Nicaragua’s past, foreign money has contributed to the country’s current unrest. In the 1970s, the US supported the regime of Gen. Anastasio Somoza — a brutal dictator who was eventually overthrown by Ortega and his revolutionary peers in 1979’s Sandinista Revolution.

This time, it’s not the US that’s supporting an unpopular Nicaraguan dictator, it’s Venezuela.

Oil diplomacy from Venezuela

I am a former Nicaraguan resident who was recently forced out of the country by violence. I am also a scholar of Latin America’s political economy. And my research in Nicaragua suggests that Venezuelan oil money helps explain Ortega’s rise — and his current fall.

Ortega was re-elected to the presidency in 2007 after two decades out of power. At the time, he was one of many left-leaning leaders in the region.

Venezuela, then led by the socialist leader Hugo Chávez, immediately began sending billions of dollars worth of cheap oil — its biggest export and most valuable commodity – to Nicaragua. According to Nicaraguan economist Adolfo Acevedo, between 2007 and 2016, Venezuela shipped US$3.7 billion in oil to Nicaragua.

“Oil diplomacy” was standard practice in Venezuela at the time. In the early 2000s, Venezuela was one of Latin America’s richest countries. Chávez used his economic brawn to support allies in Cuba, Argentina, Ecuador and Brazil by sending them financial aid and cheap crude.

Related: 5 reasons why Venezuela’s nightmare could get worse

Venezuela offered the Ortega regime unusually favorable terms of trade. His government paid 50 percent of the cost of each shipment within 90 days of receipt. The remainder was due within 23 years and financed at 2 percent interest.

This cheap fuel was distributed at market prices by Nicaragua’s government gas company, DNP. The government’s nice profit margin helped spur a period of remarkable economic growth in Nicaragua.

Between 2007 and 2016, Ortega’s government spent nearly 40 percent of oil proceeds to bolster ambitious social welfare programs, including micro-financing for small businesses, food for the hungry and subsidized housing for the poor.

These initiatives contributed to significant poverty reductions across Nicaragua, earning Ortega and his Sandinista party widespread popular support.

Between 2007 and 2017, Nicaragua’s gross domestic product grew at an average of 4.1 percent a year. The boom peaked in 2012, with a stunning 6.4 percent growth in GDP.

The year before, Venezuela had sent a record $557 million in oil to Nicaragua — the equivalent of 6 percent of the Central American country’s total gross domestic product.

Ortega’s oil wealth

Beyond jump-starting the Nicaraguan economy, Venezuelan oil also directly benefited the Ortega family.

DNP, Nicaragua’s national oil distributor, is managed by Ortega’s daughter-in-law, Yadira Leets Marín.

According to investigative reporting by the Nicaraguan newspaper Confidencial, the 60 percent of earnings from Venezuelan oil sales not spent on social programs — roughly $2.4 billion — was channeled through a Venezuelan-Nicaraguan private joint venture called Albanisa, run by President Ortega’s son, Rafael Ortega.

Related: Bloody uprising in Nicaragua could trigger the next Central American refugee crisis

The funds were invested in shadowy private businesses controlled by the Ortega family, including a wind energy project, an oil refinery, an airline, a cellphone company, a hotel, gas stations, luxury condominiums and a fish farm.

There is no public accounting of Albanisa’s investments or profits. But according to Albanisa’s former deputy manager, Rodrigo Obragon, who spoke with Univision in May, President “Ortega used Albanisa to buy everybody off in a way never seen before in the history of Nicaragua.”

Ortega’s personal wealth is unconfirmed. But reliable sources, including the Wall Street Journal, say that his family has amassed one of the largest fortunes in the country.

An uphill battle

Ortega’s landmark social programs, coupled with the lucrative business ventures that allowed him to buy support, made him the most powerful Nicaraguan leader since Somoza.

During his 11 years in office, Ortega has abolished presidential term limits, installed his wife as vice president and banned opposition parties from running in elections.

In late 2015, plummeting global oil prices sent Venezuela’s mismanaged economy into recession, and then into a full-on collapse.

Chávez’s successor, President Nicolás Maduro, was forced to cut back on oil diplomacy. As a result, in 2017 and 2018 his government sent no oil shipments at all to Nicaragua.

In effect, Ortega had to cut his landmark anti-poverty programs, eliminate subsidies on public utilities and raise gas prices at the pump.

Support for his regime eroded quickly after that.![]()

Like the dictator he helped oust three decades ago, Ortega has relied on foreign money to buy his way through challenges. Now that Venezuelan money has dried up, he’s got little left to offer his people — one more reason, protesters say, Ortega’s time is up.

Benjamin Waddell is an associate professor of sociology at Fort Lewis College.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.