‘Everyone is an enemy who’s deserving of death, rape and jail’: Death squads have returned to Nicaragua

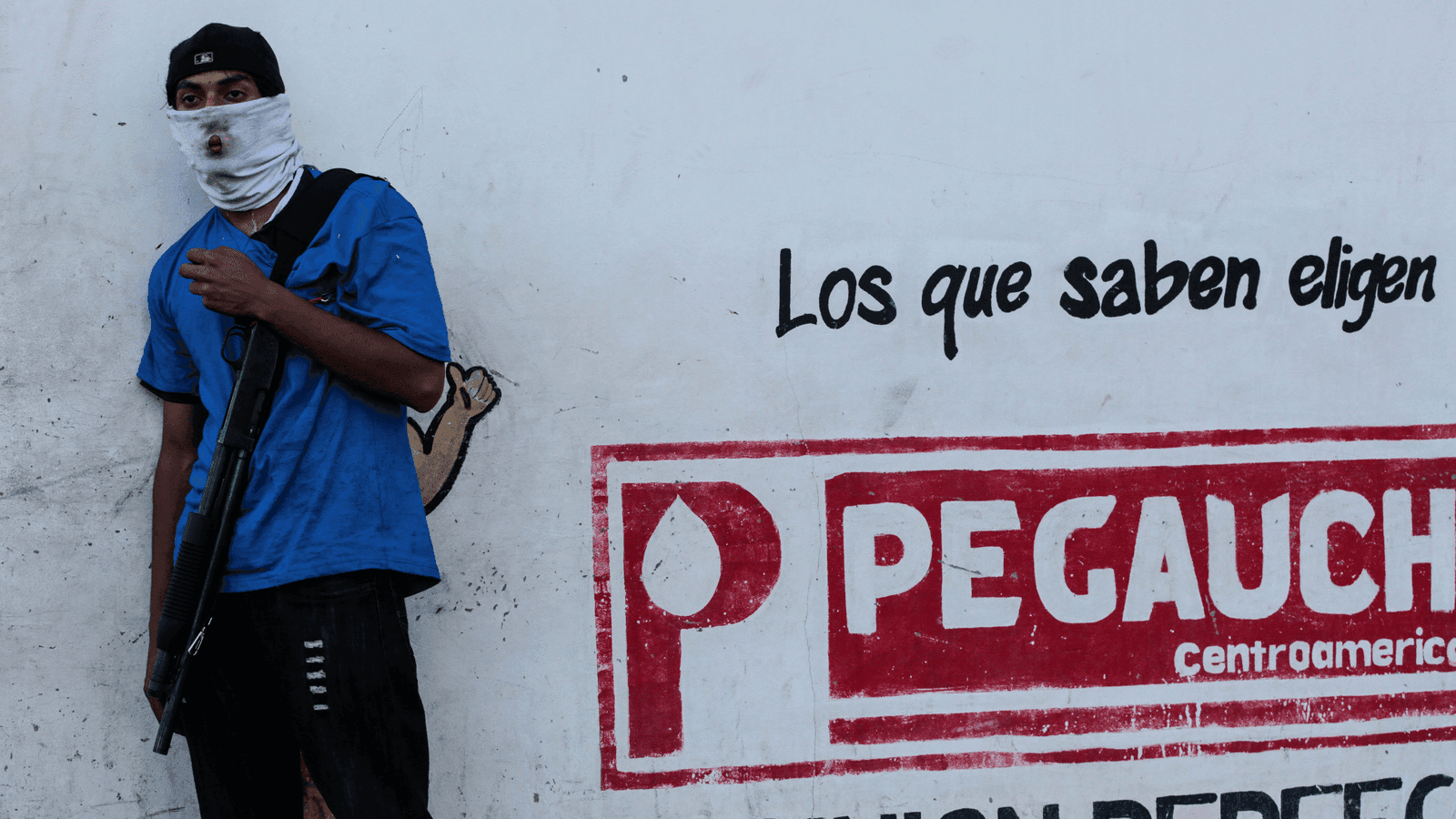

A pro-government supporter stands near a barricade after clashes with demonstrators in the Indigenous community of Monimbó in Masaya, Nicaragua, July 17, 2018.

Nicaragua is living an Orwellian nightmare.

Over the past three months, Daniel Ortega’s government of “reconciliation and national unity” has killed more than 300 people, injured thousands and abducted and disappeared hundreds more. Sandinista “death caravans” of hooded police and government paramilitaries raid towns like hordes of invading Huns, firing battlefield weapons at unarmed protesters, dragging people from their homes, torching buildings and leaving dead bodies in the street.

“We’re going to cut the head off any sonofabitch who tries to put up another barricade,” a masked paramilitary leader told a cheering crowd of Sandinista supporters after his unit shot its way into the town of Catarina to remove the paving-stone barricades that local residents erected to protect themselves against just such an attack.

President Ortega’s Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) started its transition from a ruling party to a paramilitary death squad in April, in response to a nationwide civic uprising for democracy and justice in Nicaragua. Now Ortega is installing a reign of terror in a failed state.

It’s happened so fast that the Ortega regime hasn’t had a chance to change its official letterhead, which still reads: “The Government of Reconciliation and National Unity!” The anachronistic slogan is symptomatic of a government whose messaging hasn’t caught up with its actions.

Vice President Rosario Murillo, the regime’s chief propagandist, still goes on state television daily to speak in soft tones about peace, love, national unity, human dignity and God’s love for Nicaragua. “We need to work every day to build peace and reconciliation … to advance security, peace and life,” Murillo cooed on July 17, as combined government forces of police and Sandinista paramilitaries attacked the indigenous neighborhood of Monimbó with AK-47s, high-caliber Dragunovs and heavy artillery.

“We are following God’s path for our country,” Murillo said a few days earlier, as her paramilitaries attacked the San Juan Bautista Church in Masaya and accused the priests of being “assassins.”

“The government is in a state of total denial about what’s happening here,” says Nicaraguan journalist Sofía Montenegro, who calls Murillo “Big Sister” after Orwell’s famous character in the dystopian novel 1984. “The presidential couple and their small group of followers are trapped in their own doublethink, goodthink and fake news.”

“This is more Goebbels than Orwell,” adds famed Nicaraguan author and former Sandinista revolutionary Gioconda Belli, referring to the infamous Nazi propagandist.

Snipers and slingshots

Nicaragua’s meltdown started on April 18, when students and pensioners took to the streets to march against President Ortega’s efforts to overhaul the social security system. When the regime responded with lethal force to a peaceful march, the protest bloomed almost overnight into a nationwide civic uprising against Ortega’s aging dictatorship; it was an unexpected primal scream against years of repression, bullying and the absurdity of authoritarianism. Nobody expected the situation to escalate so fast.

As the protests grew, so too did the government’s repression. First Ortega armed his Sandinista Youth, turning the youth group of party loyalists into a masked paramilitaries. When that failed to quell the protests, the government brought out the high-caliber weaponry — PKM machine guns, M24 sniper rifles and RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenade launchers — to repress a civilian population armed with rocks and homemade fireworks launchers known as morteros.

On July 17, a heavily armed mixed unit of police and Sandinista paramilitaries invaded the Indigenous neighborhood of Monimbó, which had been barricaded in self-defense for months. After overpowering the unarmed neighborhood, the government raiders lowered the blue-and-white Nicaraguan flag and raised the red-and-black Sandinista flag to pose for a picture like an occupying army.

Now most Nicaraguans just want Ortega and his wife to step down so the country can return to the path of peace and democracy, starting with early elections next year. Ortega, who was re-elected by in 2016 amid cries of fraud, rejects the calls for an early vote and says the opposition will get its chance in the next elections in 2021. His administration equates calls for early elections to a coup, and claims the government is the victim of a foreign-financed terrorist campaign to destroy Nicaragua’s constitutional order.

“We are victims of an international plot by small political groups combined with transnational organized criminal groups with international funding to overthrow the legally constituted government of President Daniel Ortega,” said Denis Moncada, Nicaragua’s ambassador to the Organization of American States (OAS). “This is terrorism disguised by political groups and disguised and supported by international groups of transnational crime.”

If that sounds like a confusing message, it’s because it is. The Ortega regime has struggled to find a coherent or consistent narrative to explain the worsening violence and chaos in Nicaragua, which until April boasted that it was “the safest country in Central America.”

The regime’s first instinct was to deny that anything was happening at all, and accuse the opposition of inventing deaths. “Imagine how low they can stoop … inventing deaths … inventing suffering … they are like vampires, demanding blood to feed their political agendas, to feed themselves … inventing deaths,” First Lady Murillo said during the beginning of the protests on April 19.

The government then spent weeks denying the existence of Sandinista paramilitaries, despite all the video evidence to the contrary. Once that narrative collapsed under its own weight, the government tried out another series of other excuses to see what would stick— everything from claiming the paramilitaries were Sandinista “community police” to calling them foreign terrorists moonlighting as coup-mongers.

But few are buying the Ortega regime’s lies. And as the crisis worsens, patience is running out.

Ortega waging ‘genocide’

Carlos Trujillo, the US ambassador to the OAS, has accused Ortega of waging a “genocide.” And Senator Marco Rubio told Nicaraguan daily La Prensa that the crisis in Nicaragua now represents a security threat to the region and the United States.

“There’s a situation in Nicaragua that doesn’t exist in Venezuela, and that’s the threat of a civil war, which would result in massive immigration, a humanitarian crisis, and a situation where drug cartels can take advantage of the chaos,” Rubio told La Prensa. He added that the presence of the Russian government in Nicaragua and its support for the Ortega regime adds an additional “threat to our hemisphere.”

Nicaraguans don’t want civil war. The country was torn apart by a counterrevolutionary war in the 1980s, during Ortega’s first go-round as president. The decade-long “contra” war left some 50,000 people dead and a country in ruins by the time the Sandinista revolution ended in 1990. When Ortega was finally re-elected in 2006, Nicaraguans gave the former revolutionary another chance to govern in times of peace and democracy. Ortega used the presidency to dismantle the country’s institutional democracy from the inside, rewriting the Constitution in his own hand, consolidating power over every branch of government, and setting himself up for president for life. Now he’s in the eleventh year and third term of what was supposed to be a single five-year term. And Nicaraguans are literally dying to get rid of him.

The majority opposition has struggled to maintain a peaceful and civic protest amid Ortega’s brutal, armed repression. With the help of the Catholic Church, the opposition’s civic alliance was able to get Ortega’s regime to sit for a short-lived “National Dialogue” last May. But talks stalled when Ortega refused to adhere to a ceasefire.

Although the National Dialogue appears more dead than alive at this point, the opposition maintains hope that the international community can get Ortega back to the table to negotiate his resignation and early elections. It’s the country’s last best chance to prevent a war.

“The National Dialogue is the only peaceful way to arrive at a democratic solution to the problems of this country,” says student leader and national dialogue member Fernando Sanchez. “People have a bad image of the dialogue because the government wasn’t participating in good faith; they were just trying to turn it into a circus. But all the other participants in the dialogue continue to defend the negotiating table as a form of peaceful struggle — we were there in good faith.”

Death toll continues to rise

In the meantime, the death toll continues to climb every day — even in parts of the country that aren’t making international headlines.

“There are more than 18 people killed in Lovago, Chontales, yesterday and nobody has said anything about it,” The Campesino Movement of Nicaragua reported in a communique on July 16. “The families of the victims want to recover the bodies. We need the support of international organizations and the Catholic Church.”

Of the 351 Nicaraguans killed during the first 80 days of protests, 306 of them were civilian protesters, according to the Nicaraguan Association for Human Rights (ANPDH). The remaining 13 percent were police and government paramilitaries, according to the rights organization. More than 289 people have died from firearms, while only two people have died from morteros, the opposition’s principal weapon.

The preliminary death toll doesn’t include the 261 people listed as “disappeared,” those allegedly buried in a mass grave behind the baseball stadium in Jinotepe, or the dozens of people killed in the days since the report was published. Nicaragua’s real death toll is likely more than 400 already.

“We’re experiencing a genocide,” says opposition figure Félix Maradiaga. “The people are searching for democracy and fighting for freedom under the tyranny of Daniel Ortega.”

For the first three months of protests, the Ortega regime focused its repressive efforts on the streets. Amnesty International denounced the government for using a “shoot to kill” strategy, which the organization claims “has been fundamentally unlawful and beset with serious human rights violations and even crimes under international law.”

The day after Amnesty’s report was released, Nicaraguan police and paramilitaries opened fire on a peaceful Mother’s Day march on Managua, killing another 17 people in what became the single bloodiest day of government repression. Five weeks later, on July 8, the regime set another single-day kill record by gunning down 38 people in Carazo during a bloody attack called “Operation Cleanup.”

When the smoke cleared, the witch hunt began; paramilitary and police are abducting people off the streets and from their homes all across the country — as many as 200 were nabbed in the rural department of Carazo alone.

“They went on a three-day rampage, grabbing people off the street, inside the market, out of businesses and busting down doors to private homes,” a local resident said, under the condition of anonymity. “The snatch squad units are a mix of riot police and professional paramilitaries. The low-grade, thuggish paramilitaries race around in pickup caravans intimidating people on the highway and in neighborhoods.”

The regime is now targeting everyone suspected of helping to dig up streets to build self-defense barricades. Police and paramilitaries go door-to-door with lists of names provided to them by neighborhood snitches, known as orejas— or ears. People are pulled from their house without a warrant and thrown into the back of unmarked Hilux pick-up trucks and hauled off to El Chipote, the government’s dreaded torture prison.

The roundups are brutal, sloppy and indiscriminate. One man, whose name has been withheld to protect his identity, says paramilitaries snatched him from his house last Sunday because he has the same name as someone else on their list. The young man, who claims he had nothing to do with the anti-government protests, was held and beaten in jail for 27 hours without food or water until police realized they had the wrong guy and let him go. “He’s traumatized,” he mother said.

Now the regime is getting more sophisticated. On Monday, Ortega’s lawmakers rammed a hastily drafted anti-terrorism bill through the Sandinista Congress, which allows the regime to weaponize its witch hunt in the courtroom. Even before the ink could dry on the new law, the Sandinistas are already processing protesters on terrorism charges. The UN High Commission on Human Rights quickly denounced the Sandinistas’ new anti-terrorism law as a thinly veiled attempt to criminalize all forms of peaceful protest.

Even Nicaraguans who fought against the Somoza regime in the 1970s say the government repression is reaching new levels.

“Even in the worst moments of Somocismo, I don’t remember a type of repression as brutal or indiscriminate as what we’re seeing now,” former FSLN comandante and Sandinista dissident Luis Carrión tweeted on Sunday. “Somoza targeted members of the FSLN and its collaborators, but now everyone is an enemy who’s deserving of death, rape and jail.”

But when everyone is targeted, everyone unites.

“Ortega didn’t lie. This really is the government of unity and reconciliation,” said Israel Lewites, of citizen activist organization Nicaragua 2.0. “Ortega is the only one who can unite feminists and the church, the campesino movement and big business, students and pensioners, progressives and conservatives. … Thanks to Ortega, we have discovered that we all have something in common: We want to remove him from office.”

Tim Rogers is Latin America editor for Fusion.