This mother and daughter have been reunited, but there is still much of their life they need to put back together

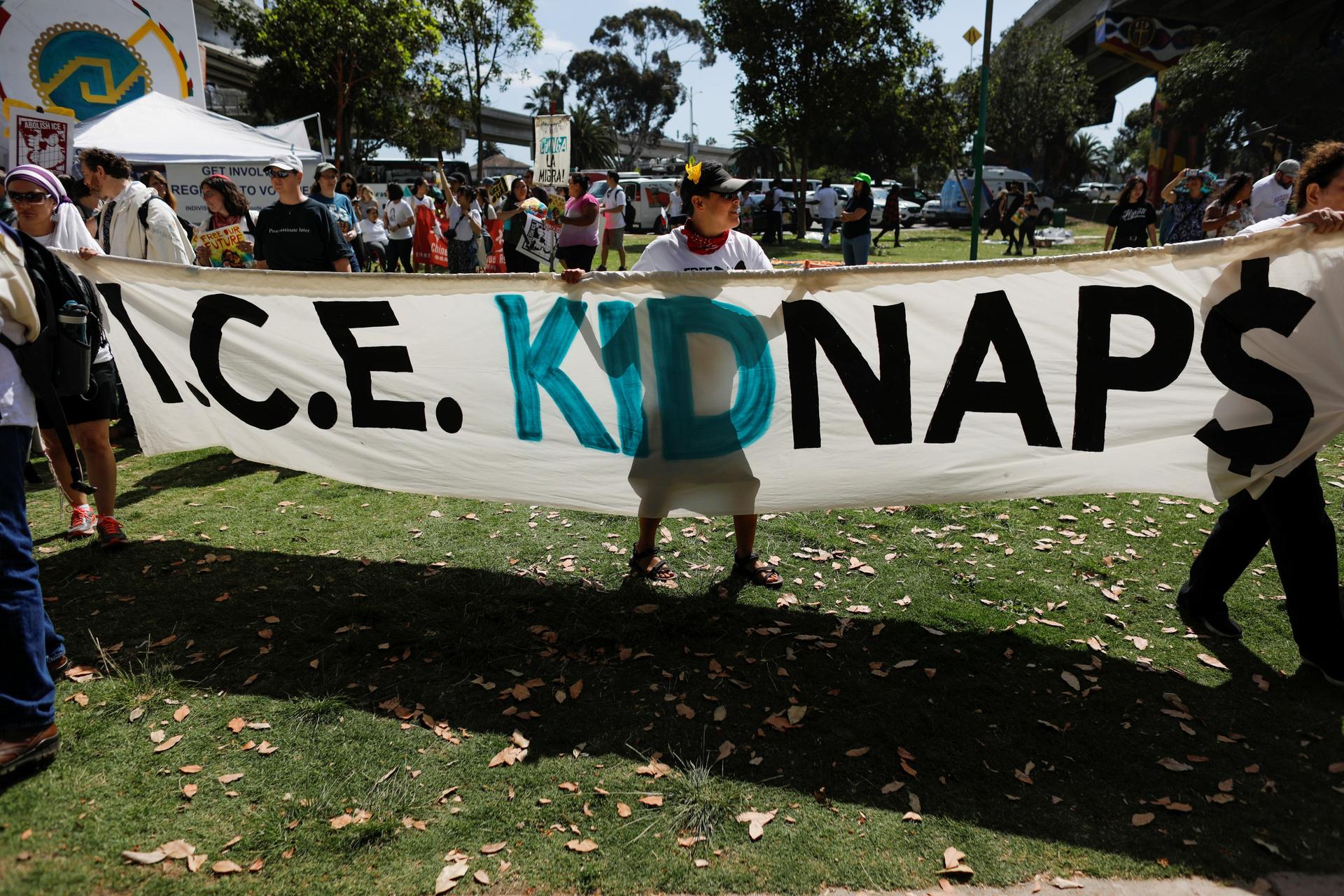

Demonstrators gather at a “Free Our Future” march to protest the expected introduction of the US Department of Justice and Immigration Customs Enforcement’s new sped-up mass immigration hearings and deportations in San Diego, California, July 2, 2018.

Sandy González-García looked like any other 8-year-old Friday, blowing out the candles on a Frozen-themed birthday cake.

You’d never suspect she spent her real birthday in a shelter on the other side of the country with other kids deemed unaccompanied minors by the government. Many of them, like her, were separated from their parents by the US government.

The Trump administration is struggling to meet a deadline to reunite those families. Two weeks ago, a federal court judge ordered all children under age 5 to be reunited with their parents by July 10, and older kids, like Sandy, to be reunited by July 26. On Monday, the government said 54 of 102 kids under 5 would be reunited by the deadline — the same federal judge extended the deadline for reuniting the rest. But another judge also ruled the government could not use indefinite detention.

So, a few parents have gotten their kids back — but it’s taken a lot of help from pro bono lawyers and volunteers who have donated housing and other resources.

Sandy was in a shelter without her mother for 55 days. She won’t talk about what that was like, no matter how many times her mom, Angélica, asks. Angélica says her daughter doesn’t trust her like she used to.

“I’m worried about her,” Angélica says in Spanish. “I ask her about it, but she doesn’t answer me. She’s not like how she was before. Before she was friendlier, happier. She used to play with her friends, now she’s scared of other kids — not sure why. And then she doesn’t sleep well. She wakes up in the night shaking, crying, screaming.”

Angélica’s lawyers have told her not to talk about what happened in Guatemala, about what prompted them to leave, beyond the fact that it involved violence. Whatever it was, it sent her and Sandy fleeing north on a costly, dangerous journey — despite what Angélica knew about President Donald Trump’s immigration policies.

“When I decided to come here … I wasn’t thinking about anything, I didn’t think about him,” Angélica says. “I just wanted to get here.”

At the Arizona border, US officials detained them in a small cell with dozens of other mothers and children. One morning they were roused at 5 a.m. and taken to a trailer, and Angélica was told to bathe and dress Sandy. When it became clear they were going to be separated, Angélica hugged Sandy and told her not to cry.

Angélica was sent to a detention center in Colorado. Weeks later, a judge released her on bond and she came to Massachusetts to stay with a childhood friend from her hometown. She eventually learned Sandy was being held at a facility in Texas

“It was such a process,” Angélica says. “I had to do paperwork like I’m her guardian, not like I’m her mother. They asked me all these questions, like how much I earn, where I’m going to live with her, what care I can give. Just to speak with her I had to send a photocopy of my ID, my birth certificate, her birth certificate. Then they listened in on our call to see if I was really her mom. All this kept me from speaking with her.”

When they did talk, Sandy begged Angélica to come and get her.

So when Angélica was told it would take weeks, even months, to process her 36-page “reunification request” in order to prove she was a fit parent with stable housing, she knew she needed help. She connected with the director of the Metrowest Workers Center, a Boston-based group created to help immigrant workers organize for better pay and healthcare.

Their network of volunteers connected Angélica with pro bono lawyers within 24 hours.

“The attorney general actually came and spoke with her,” Metrowest staffer Martha Yager says of Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey. “And then she spoke about that experience on the Rachel Maddow show that night.”

Yager says the group has been looking for ways to help undocumented immigrants since Trump’s election. First, they tried organizing volunteer response teams that would try to get in the way during ICE arrests. But that never really worked.

One undocumented worker finally told them if they really want to help, they should just come along for court appearances or immigration appointments to provide a measure of protection. They call it accompaniment.

“It’s so subtle,” Yager says. “Because I’m standing next to them and talking to them at the checkout line in the grocery, do they get treated differently? I don’t know for sure. I suspect that they do get treated differently.”

More about “accompaniment”: In New York, volunteers engage in a quiet form of advocacy for immigrants facing deportation

Volunteer Liz Garrigan-Byerly, a pastor at a local church, offered Angélica a place to stay while her lawyers worked on an emergency motion to get Sandy back. Garrigan-Byerly remembers wondering what Angelica must think of her middle-class home.

“She walked in and ‘this house is so grand,’” Garrigan-Byerly says. “At one point we went down to the basement and it just kept going. … Part of accompaniment is to set aside my own discomfort and feelings of awkwardness because that really doesn’t matter. This woman has been through hell and back. The least I can do is not think about what she thinks of me.”

There was a lot to coordinate with Angélica’s schedule.

“I’ve not been this tired since I’ve had an infant,” Garrigan-Byerly says.

They used Google Translate on Garrigan-Byerly’s phone to communicate.

“She talks a lot about what it was like in the Colorado prison,” Garrigan-Byerly says. “She feels responsibility to speak for other women who can’t.”

So, five days ago, when Angélica was finally reunited with Sandy, they invited lots of people with cameras.

“So many cameras, so many people, it felt strange,” Angélica says. “I felt like running away. But I had to wait for my girl. And when she finally arrived, I felt like I wanted to be alone with her, ask her how she was and what happened. But I couldn’t because everyone was there, I just couldn’t be alone with her.”

Sandy doesn’t seem to want to talk about the reunion.

“There were lots of people,” Sandy says. “I don’t know why.”

Now Sandy just wants to play, and she has plenty of room. A volunteer has let the mother and daughter use a small cottage in the backyard of her big New England home. It’s in a green meadow, surrounded by forest. Angélica and Sandy will eventually need help with transportation because the cottage is a bit remote. But that’s low on Angélica’s long list of concerns.

“I think we’re living through something that neither I nor my daughter fully understands yet,” Angélica says. “And we’re still living with a feeling of panic. Because if they separated us once, who’s to say they won’t do it again?”