The violent collectors who gathered Indigenous artifacts for the Queensland Museum

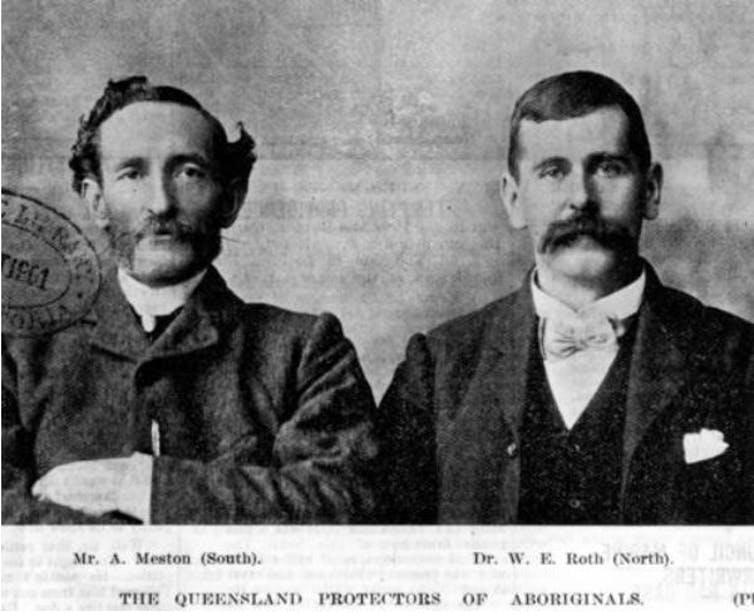

Aboriginal protectors Walter Roth and Archibald Meston between them collected over 700 objects for the Queensland Museum.

Europeans collected a huge number of Aboriginal artifacts during the colonization of Australia. These include weapons, bags, toys, clothing, canoes, tools, ceremonial items, and ancestral human remains. Many institutions that hold these items are repatriating them to Aboriginal people. While repatriation is important, what often goes unrecognized is the crucial part that collectors played in the violent dispossession of First Nations people.

My research is on the Queensland Museum’s collecting networks. Formed in 1862, the museum amassed a significant collection of Aboriginal artifacts over the following 60 years. Despite countless, undocumented interactions between makers, owners, collectors and curators, many of which were no doubt benevolent, frontier violence was a crucial aspect of the museum’s collecting.

Instances of grave robbing and body snatching as methods of collecting are not specific to Queensland. Many institutions in Australia and abroad have problematic acquisition histories, particularly in relation to the study of remains.

Activists have been agitating for the return of cultural materials for decades, and museums across Australia, including the Queensland Museum, have developed repatriation programs and policies. It works closely with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to prioritize the return of ancestral remains and sacred objects. But much material collected through violent means is still held in its collection.

While there is no evidence of the museum being directly involved in frontier killings, the use of the police, protectors, missionaries and frontier doctors as the dominant network of collectors implicates the museum as a passive beneficiary of dispossession.

In a response to The Conversation, the Queensland Museum said: “We believe these are important stories to be told and understood, and we recognize past hurts and are actively working to address these issues.

“Queensland Museum Network acknowledges that between the 1870s and 1970s, a number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Ancestral Remains, Burial Goods and Secret and/or Sacred Objects were acquired without consent or due regard to traditional lore and custom.”

Dispossessing and collecting

In the 1870s, police Sub-Inspector Alexander Douglas, noted for his role in violent dispersals of Aboriginal people, sent the Queensland Museum ancestral remains and burial goods. These had been stolen during punitive raids on Aboriginal people in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

The following decade, Francis Lyons, a “pioneer resident of Cairns,” offered the museum mummified remains he had stolen during a retributive attack on Aboriginal people. In his accompanying correspondence he wrote:

They abandoned everything except the [remains] … and it was not until after a long and desperate chase, and when their lives were in imminent danger that the[y] … dropped it.

In many instances cultural items — mostly weapons and bags — were purchased from Aboriginal people. The museum issued its collectors with tobacco for payment, itself pointing to the power imbalance of frontier currency. Yet as both Lyons and Douglas’s cases show, items were also removed after Aboriginal people were forcibly dispossessed from their country, taken from the surface, and at times stolen following raids.

Some ancestral remains held by the museum were plundered from grave sites. Remains were dug up, stolen from caves, burial trees, and bags, depending on regional customs.

While these practices may have sat outside the bounds of European expectations of death and burial, the plunderers were acutely aware of the damage they were inflicting. One correspondent informed the museum in 1880 that exhuming the remains of a recently deceased man was “too much like desecrating unless it was in the interest of science.” The idea of contributing to scientific knowledge was used to justify these actions.

Remains were also plundered from massacre sites, often decades after the event, as well as former mission sites, and sent to the museum with the sanctioning of the police and protectors.

Remains were also taken from regional hospitals, at times with the approval of the Chief Protector, the government agent responsible for Aboriginal people. Rogue doctors stole others from post-mortem rooms. In 1885, for example, the remains of South Sea Island laborers were sent from the Polynesian hospital in Mackay with specific instructions to “make them look a little ancient.”

Empire and science

The emergence of racial science in the mid-19th century, combined with the British Empire’s expansion, drove the desire for Aboriginal artifacts. Objects were collected as anything from curiosities to scientific specimens, tendentiously used to “prove” European superiority.

With an interest in the “science of man,” the Queensland Museum’s curatorial staff maintained a network of collectors across the colony through relationships forged with (predominantly) men in remote locations. They included missionaries, journalists, station managers, doctors and public servants. A 1911 request targeted these networks, stating that “every effort” must be made in “acquiring those symbols of the life of the original Australian inhabitants whose rites, ceremonies, customs and traditions are becoming obsolete and being entirely lost to us.”

However, the most profitable collectors were the government agents regulating Aboriginal people’s lives. For example, from the 1870s, the police channelled material and information to the museum. The Native Police officers became particularly important contributors.

The museum exploited their violent methods of colonial policing and practices of “dispersal” — a euphemism for massacre — and the police themselves noted this role. Following his dismissal from the force, and five years after leading an attack on Aboriginal people at Creen Creek, former Native Police officer William Armit wrote of ethnographic collecting that “no one can be more fortunately situated for such work than the Native Police officers.”

The passing of the 1897 Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act also led to increases in the museum’s acquisitions. Protectors, such as Northern and later Chief Protector Walter Roth and Southern Protector Archibald Meston, were active collectors. They became two of the museum’s largest donors with upwards of 700 items between them, both acquiring material through their official duties.

Collecting as violence

Apart from benefiting from the spoils of colonial violence, the act of collecting itself can be seen as violent. Structural violence — the social, cultural, legal, economic and political structures that marginalize groups — does not only cause physical harm, it also inflicts damage on the mind and spirit.

Collectors knew that taking ancestral remains from burial places would cause harm. Indeed one collector noted: “I feel repugnance to hurt their feelings willingly.” While procurement may have been void of direct violence, waiting for an old man to die in order to send his body to the museum, as in one case in 1915, was a malevolent act of indirect violence.

Taking materials from country also served Europeans in claiming possession, both emotional and physical, of the land. By removing Aboriginal people and culture, the invaders were writing their own narratives of ownership over the land. As settler colonies were built on the dispossession of Indigenous people, the removal of cultural materials became part of the appropriation of land.

![]() While repatriating Aboriginal cultural materials is undeniably important, we must also acknowledge the histories behind their collection. This is an important part of the repatriation process itself.

While repatriating Aboriginal cultural materials is undeniably important, we must also acknowledge the histories behind their collection. This is an important part of the repatriation process itself.

Gemmia Burden, Faculty Post-Thesis Fellow, Honorary Research Fellow in History, School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.