With Dirty Girl coffee, this entrepreneur strives to make life better for women in Appalachia

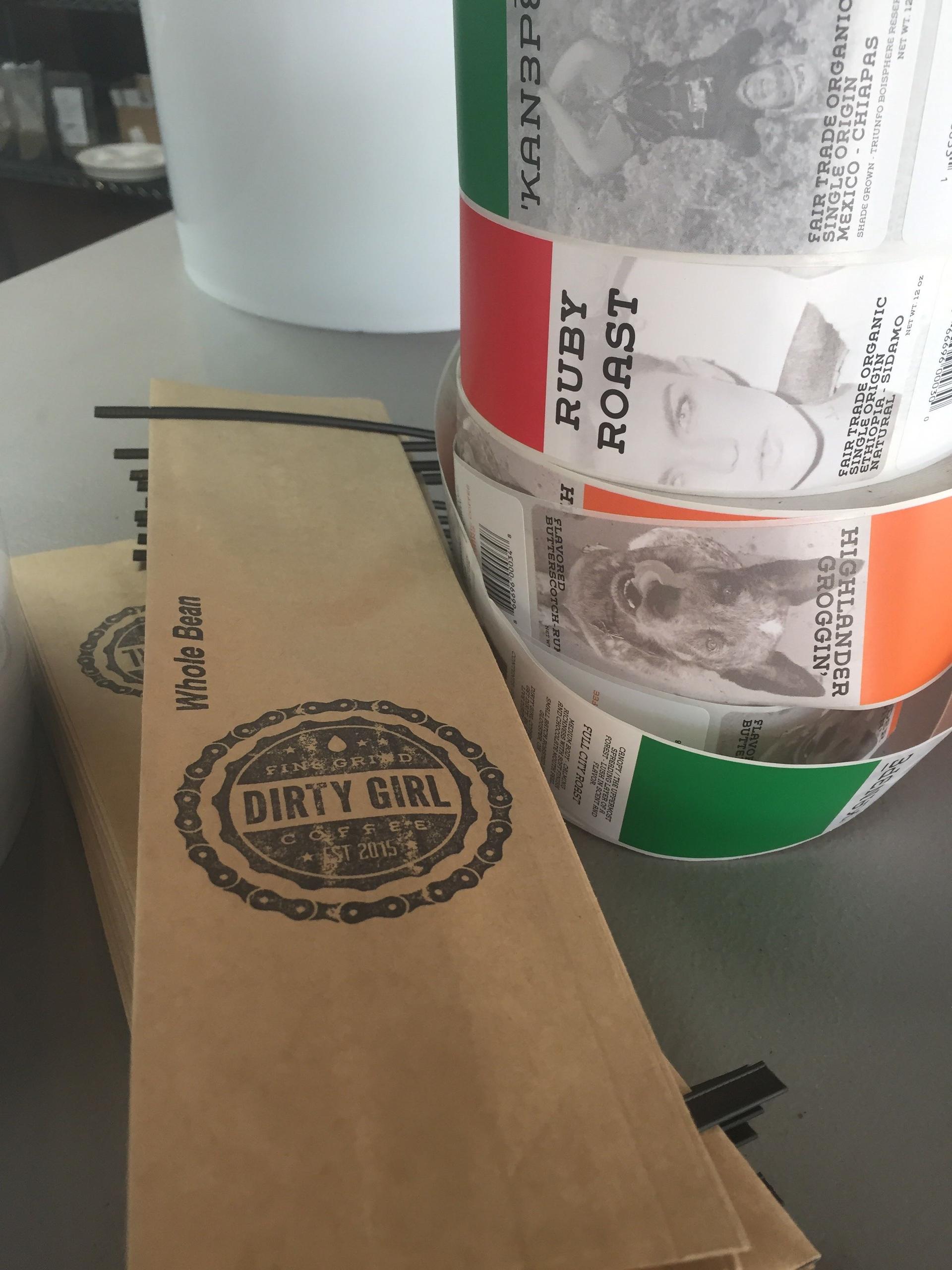

Jane Cavarozzi shows Maryrose Littler how to work the coffee roaster from her home-based operation. In addition to trying to bring businesses to southeast Ohio, Cavarozzi is also hoping to train and hire more employees of her own.

Jane Cavarozzi buzzes around the farmers market in Athens, Ohio, like she’s had too much caffeine. Fitting, perhaps, for the founder of a small coffee company.

On a brisk, sunny day, she alternates pitching her brew to new customers from her market stall and visiting with fellow vendors and networking. To Cavarozzi, coffee is more than just a business, and the market is more than just a place to sell her goods: It’s a space to meet community influencers and push her latest project through her brand, Dirty Girl.

“It’s our gateway drug,” she said of her coffee.

Making life better for women is at the heart of Cavarozzi’s efforts. The beans she buys are fair trade, organic and either grown by women or support women’s economic initiatives. That’s important, Cavarozzi says, because women coffee farmers are often vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

She also sees coffee as a vehicle to promote her greater social mission: helping support economic development and women’s advancement in the small, depressed villages around Appalachian Ohio.

Related: An Argentine startup that makes shoes from discarded tire scraps and employs single mothers

Cavarozzi’s goals are ambitious. She aims to bring skill-building, job-creating businesses to an area with little industrial infrastructure, as well as revitalize a dilapidated town center in a region where low incomes limit demand for her brand of fair-trade coffee.

She sees economic development as integral to creating opportunities for disadvantaged women here and is working to sell the region to businesses in addition to growing her own.

“The women’s focus is at the core, but in a place where there is such a depressed economic environment, you really have to start somewhere,” said Cavarozzi, who has a background in logistics and e-commerce fulfillment.

Like many small towns where political discussions happen over local produce, the farmers market has enabled Cavarozzi to meet people in the community and promote her cause. Those connections are key to doing business in Appalachia — a region marked by rugged individualism and skepticism of outsiders.

Cavarozzi is a bit of both. She lives and proudly markets her coffee as produced in Glouster, a village of 1,800 people that boomed during coal’s heyday and has declined in the decades since. But she isn’t from the region, which has, in some ways, allowed her to see new possibilities.

“I think what Jane is doing … that’s the way to make change, to be on the ground and in the community and doing the work, because then you’ve got skin in the game,” said Susan Urano, executive director of the Athens County Foundation, a nonprofit that provides funding and resources to improving quality of life in the county.

Related: Humans are damaging the fragile Galapagos ecosystem. Maybe coffee can help save it.

Urano has helped Cavarozzi build bridges by sending her new people to talk to each time one of her ideas hits a dead end. She’s also working with Cavarozzi to get more women running for local office, with plans to bring in trainers and organizations helping support women in political campaigning.

“It takes some middle-aged person who is really energetic and wants to do something,” said Sam Jones, a lifelong resident and the owner of a popular gym in Glouster, who points to blight and the aging population among the challenges of revitalizing the village.

“There are more opportunities than people care to see,” said Cavarozzi. “And somebody has to be the town crier and be annoying.”

A one-woman coffee roaster

Cavarozzi started Dirty Girl in 2015 but never expected it to take off the way it has. She currently sells her products in nearly two dozen outlets around southeast and central Ohio. Business continues to expand. At the market, she hawks specialty cold brew drinks with names like Hula Girl and Salty Bitch.

“We use coffee to open up a conversation,” she said.

Those conversations have extended to county commissioners and planners and business development councils, some of whom support her efforts.

She has also bumped up against her share of critics and bureaucratic gridlock.

The counties where Cavarozzi has focused her efforts are some of Ohio’s poorest. Like much of the country, women earn less than men, often significantly so, and many struggle to find stable work due to a lack of child care. Insufficient transportation and an addiction crisis are other problems plaguing the region.

Related: As opioids land more women in prison, Ohio finds alternative treatments

Cavarozzi says she has been frustrated by development strategies that prioritize high-wage, high-tech jobs when she believes what’s needed is more high-quality, skill-building employment. She has also agitated for investment in the struggling villages around the region rather than in the more stable cities like Athens, where a major university makes it easier to attract employers.

She calls herself a “professional irritant.” And she has burned some bridges through an approach that some see as aggressive.

Others working on regional development recognize the obstacles to attracting jobs and investment to a region both beset by pockets of deep poverty and marked with areas of wealth and higher education — a dichotomy that stirs debate about what type of development and level of wages are needed.

“A lot of our economy has been a natural-resource-extraction economy, and there are booms and busts that go along with that,” said Mike Jacoby, vice president of business development at the Appalachian Partnership for Economic Growth, a nonprofit organization that partners with state-led initiatives to create jobs and grow the region’s economy.

One way the state is doing so is by offering businesses a job-creation tax credit, but that only applies to jobs paying more than 1.5 times the minimum wage of $8.30 an hour. Companies say it can be hard to find and keep good workers for low wages. The skill and income inequalities in the region add to the challenges.

“On one hand, you have communities that really need the investment and would welcome any new construction, any kind of jobs,” versus the city of Athens, where putting a new building up, said Jacoby, “isn’t necessarily always welcome.”

Organizations, including APEG, say they support what Cavarozzi is doing — even while some officials regard it as overly ambitious or unachievable. And despite running up against roadblocks, she is starting to see some progress.

Longtime friend and former colleague, Joe Teno, the founder of the performance apparel line QOR, is in the process of setting up an e-commerce fulfillment center in Athens County with Cavarozzi’s help.

The center will initially hire around 10 people and will invest in training them, Teno says. While he’s reluctant to speculate on the impact the business could have, he believes that if they are successful in the region it could draw interest from other similar types of businesses, too.

‘Working the problem’

Cavarozzi knows achieving her goals will take time and tenacity.

But in being a nuisance, she hopes to start bringing people together who should be talking and sharing ideas to find ways to “work the problem,” one of her catchphrases.

Her latest success is getting a regular block party going on the first Friday of every month in Glouster. She’s hoping to spread a message about the need to buy local and support local business initiatives — by exposing people to the town and its buildings, some of which she’s hoping to get investors interested in rehabilitating.

She still doesn’t pay herself and she still makes deliveries and crafts each batch of orders — though she has hired a local woman to help with roasting and marketing.

She came to the company through Maryrose Littler, a former employee who asked for a job by proclaiming to Cavarozzi that her two favorite things were coffee and women.

“For me and for a lot of young women in the foothills of Appalachia, it can be kind of difficult to find a good gig,” said 19-year-old Littler, who recently moved out West where she’ll start college in the fall.

She said she liked that her work with Cavarozzi taught her not just about coffee but how to communicate in a genuine way. Someday, she says, she, too, would like to give back to her community.