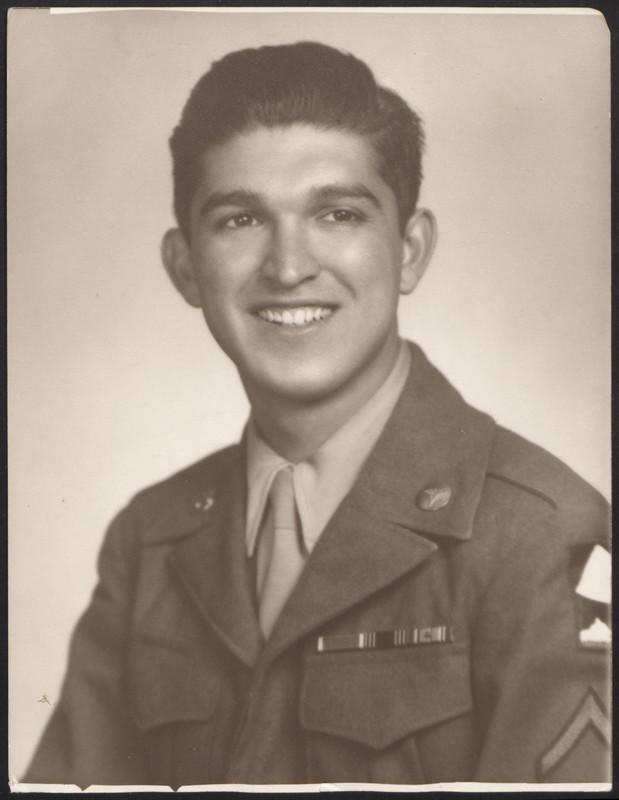

Tony Acevedo at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's 20th Anniversary Tribute event in Los Angeles, February 2013.

On the night of March 20, 1945, a 20-year-old Mexican American soldier named Tony Acevedo lay in the cold barracks of a Nazi concentration camp.

He pulled out a diary he kept hidden even from his comrades and began to write.

“Goldstein’s body was returned here today for burial — he was shot while attempting to re-escape. So they say, but actually was recaptured and shot through the [fore]head.” It was Private Morton Goldstein of Egg Harbor, New Jersey. Acevedo, an army medic, later said he examined the body himself.

It’s largely thanks to the diary kept by the late Anthony “Tony” Acevedo, that the world knows the fate of many American prisoners of the Nazis, like Goldstein.

“His list was really one of the primary resources for our knowledge and the army’s knowledge of what the fate was for many of these men,” said Kyra Schuster of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum. “And when I asked Tony, ‘why did you keep the diary? Why did you keep the list?’ Because certainly if he had been caught, he would have been severely punished or beaten or possibly even killed for it. And he just looked at me and said ‘It was my moral obligation to do so.'”

Acevedo’s ‘moral obligation’ chronicled daily life at Berga, a sub-camp of the Buchenwald concentration camp, and a death march in the final weeks of World War II in Europe.

He’s also “the first Mexican American, Catholic, Holocaust survivor who registered with the museum,” Schuster said. The Nazis saw him as “undesirable.”

Acevedo died on Feb. 11, 2018. He was 93.

He was captured at the Battle of the Bulge, in January 1945. A month later, he was one of 350 American GIs selected to be slave laborers at Berga.

“It was hell,” he said in a 2013 oral history interview with the Holocaust museum. “It was just one thought after another thought, of praying that there wouldn’t be another day like this.”

‘Kill them with kindness’

Acevedo was born in San Bernardino, California, in 1924 to undocumented parents with Mexican citizenship. His mother died when he was a toddler and his father, an engineer, remarried. But in 1937, his family was deported to Mexico and settled in Durango.

Acevedo dealt with cruelty, hardship and violence from a young age.

It helped him find the words he would live his life by: “If they treat you wrong, kill them with kindness.”

According to his son, Fernando, this mantra developed in response to growing up with an abusive father.

“My grandfather would pistol-whip my father,” said Fernando. “Call him many names, wish that he had not been born. And he would point to the neighbor down the street, and say … ‘I wish you could be like him.'”

Despite that, Fernando said Tony’s response was always patience and compassion.

“What I remember about my dad is that he had this penetrating smile,” Fernando said. “[So] that, you know, you wanted to get to know him. I know it sounds magical and far-fetched, but that’s always how he was. And it used to irritate me, because I was like a snot-nosed kid that was wondering why I couldn’t get my way about something or why things didn’t happen the way I wanted them to, but my Dad would always say, ‘Just have patience.'”

But there was something else Fernando remembers about his father.

“He would just walk away, go to the porch, or some part of the house where he would be able to be by himself, and he would just start crying,” Fernando recounts.

When Acevedo was a teenager in Durango during the beginning of WWII, he and a friend intercepted and deciphered a suspicious morse code message. The two boys informed the authorities and two German agents, who had allegedly been communicating with German submarines, were arrested.

Despite living in Mexico, Acevedo, a US citizen, received a draft notice from the US Army soon after Pearl Harbor. He went willingly, partly to escape his abusive father.

Acevedo, who wanted to be a doctor, was trained as a combat medic. His unit arrived in France in December 1944, and was immediately rushed to the front to try to turn back the final German offensive of the war: what became known as the Battle of the Bulge.

After 10 days in combat, his company was surrounded and forced to surrender, early in January 1945.

‘Take two steps forward’

Acevedo was captured and sent to a prisoner of war camp in Bavaria. About a week after he arrived, according to his interview with the Holocaust museum, the Gestapo, or the German secret police, pulled him in for a special interrogation. Somehow, they knew who he was; where he was born and where he grew up. They taunted him about being deported because his parents were undocumented.

According to Acevedo, they believed he was a spy. Back in Mexico in 1940 or 1941, Acevedo said he was involved in getting two Germans in trouble with the authorities over a morse code communication. Incredible as it seems, the Gestapo knew about this.

They spent a night torturing him to try to get the truth.

“And I kept denying, and everything I denied, he [the Gestapo] slapped my face,” Acevedo told the Holocaust museum in 2013. “Then he started to put needles in my fingernails.”

Life in the POW camp was tough, but not in comparison to what was to come after about a month.

“We were forced to come out of the barracks and line up,” recalled Acevedo. There were about 4,000 GIs in the camp at that time. “And then the commander said ‘All American Jews! Take two steps forward!’”

A selection was being made. At the time, the GIs had no idea what for, but according to the USHMM, an order had arrived for 350 GIs who were to be used as slave laborers.

Acevedo recalled how Jewish GIs reacted to the line up in different ways. Some tried to etch out the letter H (for Hebrew) on their dog-tags or to bury them. Others, like his friend Norm Fellman, refused to bury their identity and stepped forward. Tony was impressed with how many men “held on to their faith.”

The Germans started with the known Jewish soldiers, then those with “Jewish” names, or who looked Jewish. But there weren’t 350. “Then the commander came by,” recalled Tony, “and he poked at me, pulled me … put me up front as an undesirable.”

What followed is a familiar story to those who’ve studied the Holocaust, but few know this happened to American POWs. Acevedo remembered how the Germans put them on train, crammed into a boxcar “like sardines … You couldn’t kneel, you couldn’t squat — for six days.”

There was no food and no water. The men scavenged snow from the sides of the car. There was nowhere to relieve themselves. All of this continued for six days, until they reached the concentration camp at Berga.

“When we got to Berga, well, they took us to the cremation center to bathe us,” Acevedo said. “We didn’t know that that was for bathing. We thought they were going to cremate us.”

The US soldiers passed corpses of gassed prisoners.

“They took us to the gas chambers. They took us there and we saw the tubings, the pipes, up ahead. One was for gas. The other one was for water.”

The soldiers were lucky, and only got showers.

But Acevedo said that incident alone broke some of the men.

Then began a brutal life of slave labor, digging tunnels of hard rock, and all on starvation rations. Within a week, the soldiers started dying. Any caught trying to escape — like Goldstein — were executed.

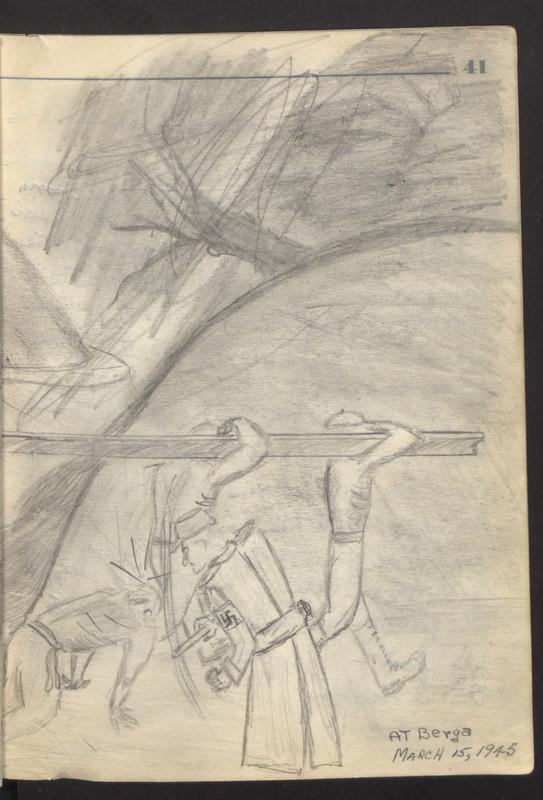

Acevedo started his diary, slipping it inside his pants to hide it from the Germans. It included a list of those who perished.

In early April 1945, with the allies closing in and snow still on the ground, the Germans ordered the emaciated prisoners out of the camp. They were forced to march for more than 200 miles — a death march. Men were dropping all the time. They used a cart to carry those who couldn’t move and those who died were simply left where they fell.

On several occasions, the GIs saw groups of massacred civilians and even witnessed a massacre taking place.

“Up ahead we noticed that the Germans were slaughtering political prisoners,” said Acevedo. “We called them political prisoners, but turned out to be they were Jewish fellows and families: children, mothers and older fellows.”

After more than two weeks, very suddenly most of the guards fled. US tanks soon appeared.

‘All the fellows cried’

“God! God liberated us,” recalled Acevedo. “And all the fellows cried, and some kneeled down and cried and kissed the ground because [of] the liberation.”

Their rescuers refused to believe they were Americans at first. Acevedo was 5’10” but he was down to just 87 lbs. He remembers how he was pulled up onto the American tank “like a rag doll.” His buddy Norm also made it. He was 6’4” and down to 86 lbs.

They were lucky to survive. According to the Holocaust museum, only about half of the 350 US POWs sent to Berga returned home.

Decades later, the memory of liberation could still bring Tony Acevedo to tears. The excitement, he said, literally killed some of his friends just at the moment of liberation. Others died in the following days, their bodies too weakened to survive.

Acevedo did not become a doctor. His artistic skill led him to a successful career in aerospace design.

He had his troubles, yet his son Fernando remembers how Tony was almost always smiling.

“He was this dancing person,” Fernando said. “He loved to dance. Whether it was the cumbia, you know, from Cuba, or any kind of Latin music, he would just get into this dancing. And he used to do this around the house with my mother, you know, that he was married to for 40 years. He was just jovial. He was happy. He was laughing. He liked to play jokes. He never walked around with a frown.”

Acevedo proudly flew the American flag and the POW flag on his lawn. He was a conservative Republican but according to Fernando, he had recently become concerned that politicians here in the US were pitting people against each other.

“He had a hard time with what he saw going on, especially this last year,” said Fernando. “We would watch the news, and switch it from different stations. He just did not like what he saw.”

Later in life, Tony Acevedo was a frequent guest speaker at schools and colleges across southern California. He wanted to raise awareness, to help prevent anything like the horror he experienced from happening again. He warned students who scoffed that “it could happen.”

He told the students that that there is only one way to fight hate. “They must learn to be able to love more, to understand, and to be to get along with each other, and respect each other, and respect others.”

“Kill them with kindness,” he said. “If they treat you wrong, kill them with kindness.”