In Paris, volunteers rally to feed and house young people who are migrating to France on their own

Migrants feed a swan next to their tents that are installed on the banks of Canal Saint-Martin in Paris, France, Feb. 15, 2018.

It’s lunchtime in the Pali-Kao public garden in northern Paris. More than a hundred teenagers, mostly boys, have come here to eat, meet friends and play games.

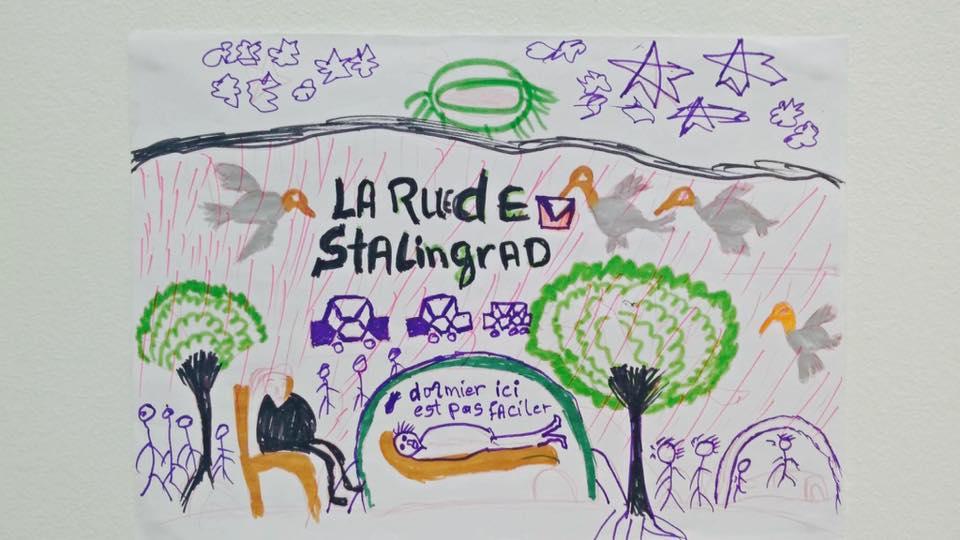

Almost all of them are teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19. They’ve come from Afghanistan and many different African countries. Once they get to France, it can take authorities up to 14 months to assess whether they are eligible for asylum as minors — a key recognition for kids who can then benefit from children’s welfare services. In the meantime, however, many of them end up sleeping on the streets, even though the law says they should be housed immediately.

Twice a week, volunteers place large bowls of hot food on picnic tables in this park. Today’s menu: rice, lentils, pastries and bananas. The kids play soccer and table tennis here, even in the cold and snow.

Faisal Mokhtar is a 17-year-old from Sudan. He arrived in Paris last May and says he, like many of the teenagers around him, is homeless.

But there is help nearby. Volunteer Agathe Nadimi is handing out cell phones and SIM cards to the teenagers. She’s a business school teacher and a powerhouse advocate in the city who organizes many relief efforts for these young people. She estimates the number of foreign youth living on the streets to be about 300, but says there could be many more.

“It’s very difficult to come up with a precise number because most of them stay in hiding everywhere in the city,” she says. “So some sleep on construction sites, others in parking lots, train stations or metro stations and switch stations the next day because they were harassed the night before. So the ones I know about are the kids who show up at pre-determined meeting spots for minors, or those I’m told about by other volunteers.”

Advocates like Nadimi work around the clock to try to provide services for those teenagers while they await asylum decisions. And it’s a considerable task because a record number of unaccompanied foreign youth — almost 15,000, according to the latest government figures — were recognized as minors in France in 2017, an 85 percent increase over the previous year.

Even when it’s not too cold, those homeless kids can’t count on much sleep. Police regularly chase away people sleeping in the streets to prevent small camps from taking root. In the coldest weeks of winter, the city opened some gymnasiums for the homeless. But Nadimi says young people didn’t feel comfortable sharing a crowded space for the night with random adults, some of them troubled.

Nadimi says during the last cold spell, she found spaces for up to 90 kids every night, spread over a network of volunteers and NGOs in Paris and hotel rooms paid for by Doctors Without Borders.

Last month, when sub-zero temperatures froze the city, Interior Minister Gérard Collomb, in a videotaped interview, denied the presence of minors on the streets. When Collomb was pressed by an activist who said he’d seen dozens of kids on the streets with his own eyes, Collomb replied: “Well, there are a number of minors who refuse to be housed.” As the activist nodded in disbelief, Collomb added with a smile: “I follow this question daily.”

Nadimi was outraged by the suggestion that youth freezing on the street would turn down a home for the night.

“He’s talking nonsense,” she says. “I am appalled by how little these politicians know about what’s happening in the field. I invite them to spend just one day with me and those kids so they can see who they are, that they are minors and that we rely heavily on volunteers and graciously loaned indoor spaces to feed the kids and keep them warm when it’s snowing outside.”

Nadimi helps organize a network of Parisians that can house about 80 teenagers on any given night. One of those Parisians is Delphine Dufriche. Dufriche says in the year and a half since she started housing migrant youth, 30 different kids have crashed on her couch, each for a couple of nights in a row.

When asked if it doesn't feel weird to have complete strangers share her apartment, she laughs.

"Yes, it is crazy to live like this, but it’s not as complicated as it seems,” she says. “At first, when this 16-year-old kid Rahim came over to sleep on my couch, I was worried and I asked a friend to stay with me. But I’m 46 years old, the age these kids’ mothers would be, so I think that makes this kind of relationship simpler because they have respect for someone their parents’ age.”

Another volunteer, Manuela, who prefers not to give her last name, also has occasionally offered a couch to these young migrants. She says she was haunted by the images of wrecked migrants’ boats in the Mediterranean and kids living on the streets. She felt she had to do something. Last year, she housed about a dozen young migrants. But in recent months, she’s mostly been taking care of just two teenagers. She’s committed to helping them sort out their new lives in Paris.

“I fought to get them into school,” she says, “so that’s a lot to undertake. There’s paperwork, vaccines, doctors’ appointments, everything. It’s time, money and sustained support. For the teenager over 18, it’s trying to find legal solutions and opportunities for him.”

Agathe Nadimi connects volunteers and teenagers who need help through social media. Every other day on Facebook she describes a new harrowing situation, like this 15-year old who is hungry and cold, speaks no French, and is completely lost. Would someone have a spot for him?

Many of these youth come from former French colonies in Africa like Cameroon, Chad and Guinea. Nadimi says they think that heritage will give them a better chance to be accepted and obtain asylum. But in the end, she says no one cares where they’re from. As the mother of a 15-year-old boy herself, she says she’s heartbroken to see those teenagers ignored by the system.

“It’s upsetting because I would not let my son sleep even one night on the streets of Paris,” she says.

Many of the kids Agathe Nadimi has helped call her maman Agathe, or mommy Agathe. And she says she puts things in perspective for them:

“I tell them, you know, we don’t know what tomorrow will bring,” she says. “If my country was at war, or if my son had to travel far from me to the other end of the world, I’d be relieved to know that there are at least a few people around to help him out. I try to do for others what I’d like others to do for me.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!