Social media users in America are stoking Ethiopia’s ethnic violence

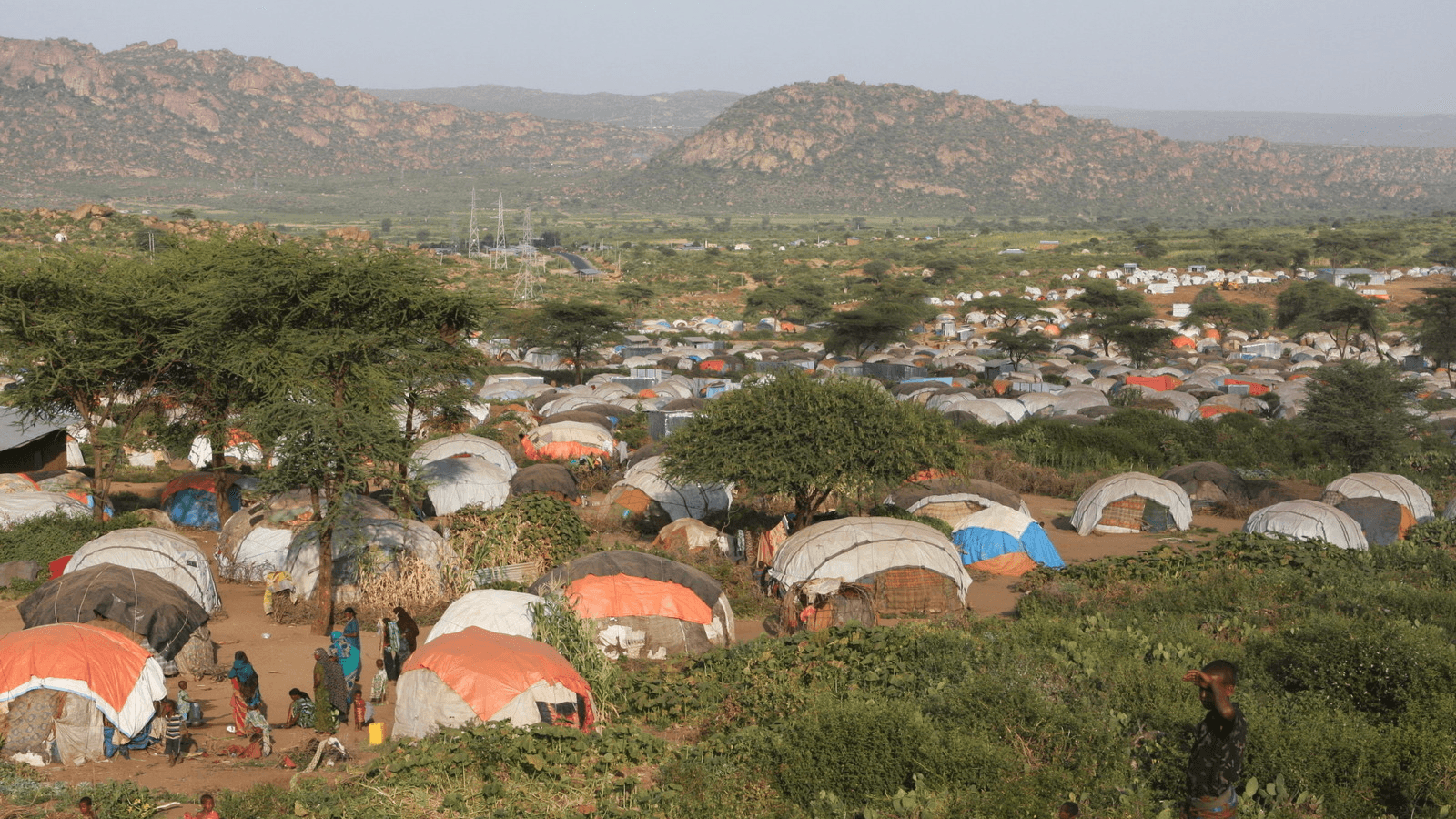

Overlooking the camps for Somalis displaced by ethnic violence in the lee of the Kolenchi hills in the Somali region.

The Ethiopian diaspora in the US uses social media to great effect in shaping coverage of events back home, especially the protest movement that has pummeled Ethiopia for more than two years

During that time, social media has proved itself a double-edged sword in Ethiopia: It’s capable of filling a need for more information due to limited press freedom and frequent blanket shutdowns of mobile internet, but also of pushing the country toward even greater calamity.

Internecine fighting that broke out last year between the country’s ethnic Oromo and Somali killed hundreds and displaced a million people throughout the neighboring Oromia and Somali regions, according to the International Organization for Migration.

Many of the displaced and those assisting them have alleged that the ethnic unrest has been leveraged for political ends. The suspected perpetrators included the usual suspects at the regional and federal government levels, powerbrokers moving in the shadows to influence events on the ground to their advantage and those you might not so readily suspect, such as Ethiopian-diaspora cab drivers coming off shifts in Washington, DC, who tweeted ethnic-laced vitriol on their smartphones.

“They live in a secure democracy, send their children to good Western schools and are at liberty to say whatever they want to cause mayhem in Ethiopia,” says Sandy Wade, a former European Union diplomat in Addis Ababa during the protests. “They call it freedom of speech and they abuse it to their heart’s content.”

Successive waves of emigration during decades of tumult in Ethiopia have formed a worldwide Ethiopian diaspora of around two million people. The largest communities are in the US, with estimates varying from 250,000 people to about one million.

The diaspora, understandably, follow events in Ethiopia very closely. Most Ethiopian emigres loathe the ruling Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) party — many overseas Ethiopians fled their homes after suffering at the hands of Ethiopia's authoritarian government — and embrace satellite television and the internet as ways to influence the political process at home.

The Oromo, Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group at 35 percent of the population, were the original protesters at the end of 2015.

Then in 2016, the Amhara, the second largest ethnic group, began to protest about the same things, including government corruption, lack of political representation and fair elections, and curtailment of civil liberties and freedom of speech. Although there was an element of solidarity, the two protest movements never fully coalesced — due in part to the historical tensions between the Amhara and Oromo. At the same time, the government was terrified that the two groups would unite; together, the Oromo and Amhara account for around 65 percent of the country’s population.

Because of the scale and momentum of the Oromo protests, which have remained the most widespread and stubborn, many increasingly see this movement as a pathway to bringing down the government, especially as it’s finally having a tangible political impact.

This Jan. 3, the government made a surprise announcement to close a notorious detention center and release more than 500 prisoners, including those from political parties, in an unprecedented capitulation to internal pressures.

Then on Feb. 15, in another apparent bid to placate the turmoil, Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn announced his shock resignation as “vital in the bid to carry out reforms that would lead to sustainable peace and democracy.”

By using opposition contacts in Ethiopia, a growing diaspora movement of writers, bloggers, journalists and activists have flooded Twitter and Facebook with news sources that, they say, contradict inaccurate accounts pushed out by Ethiopia's mostly state-run media or by muddled foreign reporters.

Diaspora social media and satellite television channels broadcast from the United States, such as Oromia Media Network and Ethiopian Satellite Television, do produce original reporting. But they are one-sided and virulently anti-EPRDF, as are the views of many followers, resulting in another side to diaspora social media coverage.

After clashes between police and protestors at the Oromo Irreecha festival in October 2016 left more than 100 people drowned or crushed to death during a stampede, social media sites buzzed with claims that a police helicopter had fired into the panicking crowd; the helicopter was actually dropping leaflets wishing participants a happy festival.

Overseas activists called for "five days of rage." Although it is not clear what effect this call may have had, the following week foreign-owned factories, government buildings and tourist lodges were attacked across the Oromia region. The government declared a six-month state of emergency.

“The problem is a lot of things people view as gossip if heard by mouth, [but] when they read about it on social media they take as fact,” says Lidetu Ayele, founder of the opposition Ethiopia Democratic Party.

That state of emergency was finally lifted in August 2017 — having been extended at the six-month point — with the government judging the country’s situation stable enough. By Sept. 12, however, a riot in the eastern city of Aweday left up to 40 dead and triggered further ethnic violence and mass displacements.

“They were crossing their arms and shouting ‘Jawar! Jawar!’” 52-year-old Adamali Meagsu says about local Oromo running amok and burning Somali houses in his village in Oromia.

The arm crossing is explained by the following: When Ethiopian runner Feisal Lyles finished the marathon at the 2016 Rio Olympics, he crossed his wrists above his head, giving further impetus to a gesture symbolizing shackles and that had already been widely shared through social media to symbolize the Oromo’s struggle against the government. The gesture continues to be been mimicked throughout Ethiopia and around the world among the diaspora.

The rioters’ exhortations referred to Jawar Mohammed, a prominent US-based Oromo opposition activist commanding a huge social media following. To many he is an inspiration; to many others — both Ethiopian and foreign — he’s a highly dangerous figure.

The unprecedented duration and scope of these protests, while steeped in so much vitriol, have rendered the country’s inherent ethnic fault lines more fragile and susceptible to abuse and manipulation.

Since 1995, Ethiopia has applied a distinct political model of ethnically based federalism to the country’s heterogeneous masses — about 100 million people who speak more than 80 dialects.

In a country as diverse as Ethiopia, the cumulative effect of ethnic slander should not be underestimated, observers note, especially where historical grudges exist between main ethic groups.

Much ethnic sniping online is directed against Ethiopia’s Tigrayan minority, constituting only 6 percent of the population, due to the firmly held belief that a Tigrayan elite run the EPRDF and are to blame for all of Ethiopia’s corruption, inequities and wrongs. Ordinary Tigrayans living outside their home region of Tigray are highly vulnerable to ethnic-based agitation and have already suffered attacks.

In Rwanda, radio programs such as Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines spread much of the toxic hatred that fuelled the country’s genocide. Social media appears similarly capable in spreading untruths and ethnic barbs in Ethiopia.

“I think the population, even the hot-blooded youth, are keenly aware of the real danger of disintegration and its horrible consequences,” Jawar Mohammed says. “That is why they have not been as aggressive even in the face of an ever-weakening regime. This regime could be overthrown in a week’s time.”

A day after the prime minister’s announcement, another state of emergency was declared. Ethiopia has always viewed itself as different to, even separate from, the rest of Africa. But there’s increasing concern it could repeat the same mistakes and disasters seen too many times on the continent.

“There is no guarantee that Ethiopia will not descend into further chaos and violence,” says Awol Allo, an Ethiopian lecturer in law at Keele University in the UK. “There is no magic formula here that doesn’t exist in other African countries.”