Janitor Georgina Hernández and her daughter at a hunger strike outside the State Capitol in Sacramento, California.

When I first met a janitor named Georgina Hernández, she was timid and teary-eyed. She had worked at a hotel where she cleaned the lobby and, in a lawsuit, said she was raped on the job by her supervisor. She was a single mom, supporting her children.

“When you need the job, you become a victim by not having the courage to say no,” she told me in her native Spanish. “And if you say no, you are going to lose the job. I didn’t have someone to tell or anyone I could trust.”

I met Hernández in Los Angeles in 2015 while reporting for a project that started long before the #MeToo movement. “Rape on the Night Shift” — which became a documentary — exposed how immigrant janitors, working alone at night in isolated buildings, are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence.

We spent months talking with janitors and following a watchdog group of undercover investigators in Southern California. They are former janitors who go into buildings at night to make sure workers are being paid fairly.

Hernández was one of the women these investigators met on the job. She cleaned a movie theater and a restaurant, scrubbing grease off the ceiling fans.

“I worked from 11 at night until 11 in the morning,” she told us. “I didn’t get overtime, I didn’t have rest breaks. I worked without stopping.”

It was another job — cleaning a hotel lobby — where her supervisor harassed her constantly. In a lawsuit she filed, Hernández alleges he sexually assaulted her in the parking garage, where there were no security cameras.

“It was an experience that I wouldn’t wish upon any woman,” she told me back in 2015. During that interview, she could only describe what had happened to her as “sexual harassment,” and she could hardly even make eye contact with me.

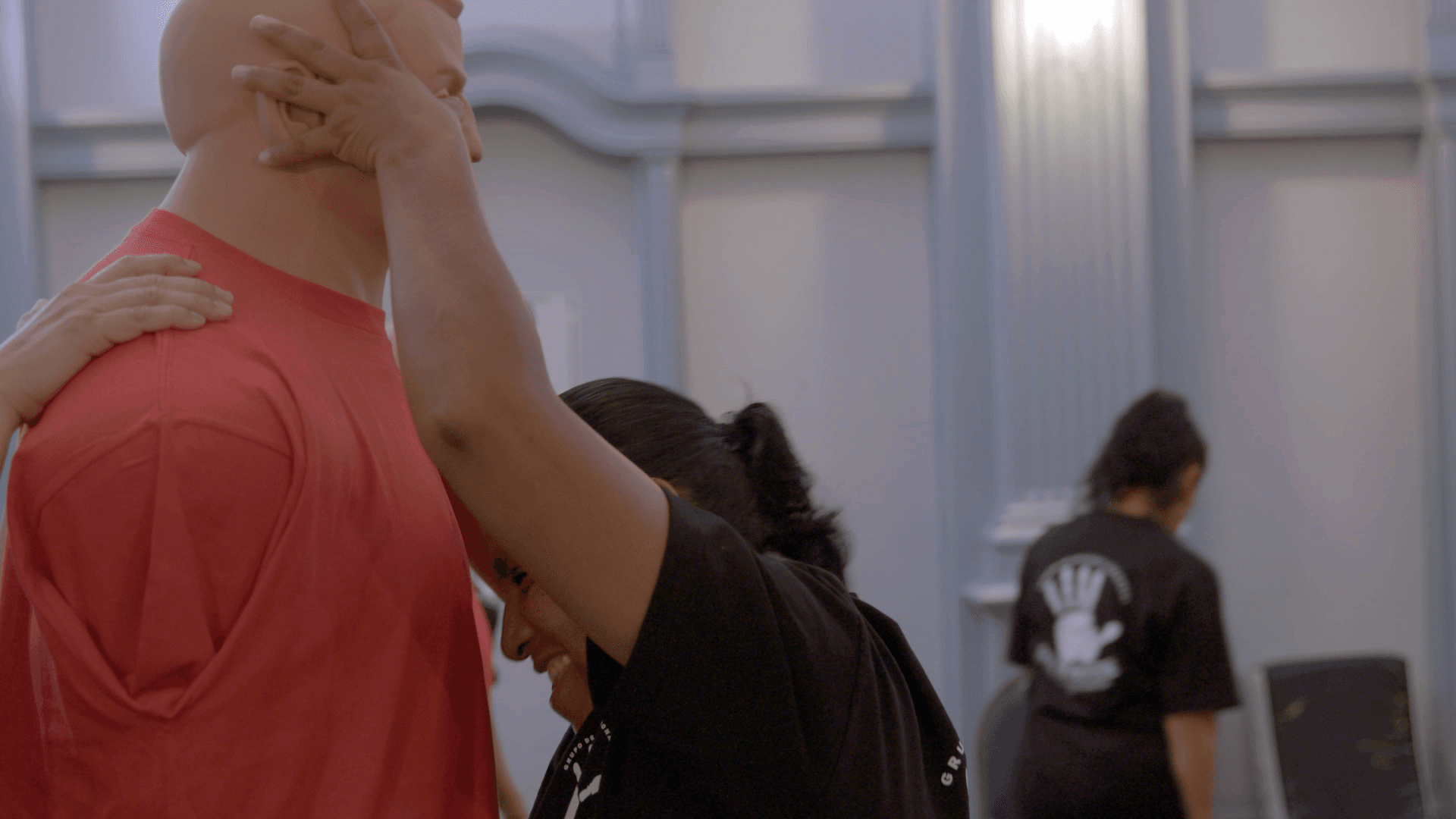

Today she’s a different person. When I meet up with her in early December, Hernández is leading other women in a self-defense class in downtown LA. They form a circle and practice how to shout “No!” to fend off an attacker.

Hernández has a big grin on her face as she shows other women how to make a fist to punch someone in the nose.

They’re practicing on large mannequins with muscled torsos dressed in red T-shirts. Hernández is not intimidated by the menacing expressions on their plastic faces as she digs her thumbs into the mannequin’s eye sockets.

I ask her how it feels.

“Good! I’m mad!” she says, banging her fist into her palm. “I wish I could do it for real!”

Later, her dark ponytail swings back and forth as she kicks a plastic mat hard, practicing how to aim for an attacker’s testicles. Part of the exercise is learning how to say that word aloud.

“My life is new,” she says. “I almost don’t even recognize myself. Now I’m confident in myself. I’m not afraid. Before I was afraid of my own shadow. I’m not afraid of anything anymore.”

Hernández's transformation, from a frightened worker who felt alone in her struggle to a strong group leader willing to speak up for herself and other women, came after she met other women janitors who had also been harassed or raped on the job by their supervisors.

Some of those women had watched a Spanish-language version of the documentary “Rape on the Night Shift” at screenings sponsored by California’s janitors’ union, SEIU-United Service Workers West. After many of those screenings, women stood up and shared their own stories of abuse. Georgina became part of a larger campaign to fight back called “Ya Basta” — “Enough is Enough.”

The janitors began protesting in the streets. They put up billboards across the San Francisco Bay Area urging: “End Rape on the Night Shift.” And they organized a push for legislation that would increase protections for janitors. It was backed by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher of San Diego.

“We’re talking about immigrant women, many undocumented immigrant women who, in a very personal way, need safety in their workplace,” Gonzalez Fletcher says. “And we’re fighting not only the janitorial companies but the business owners who hired those janitorial companies.”

The new law requires sexual harassment training for all janitors and their supervisors. Companies that don’t comply can’t do business in California.

“We wanted to make sure that the workers knew their rights, that supervisors knew what the law was as well,” Gonzalez Fletcher says. “We’ve got to continue to say, ‘Who do we hold responsible? And how do we hold them responsible? And what happens for companies who don’t take allegations seriously?’”

The bill also creates a registry of janitorial companies, so the state can keep track of subcontractors and tiny fly-by-night operations.

As she lobbied for the bill, Gonzalez Fletcher got some of her colleagues in the legislative women’s caucus to wear a janitor’s uniform for a day.

Georgina Hernández was one of the janitors from across California who joined a five-day hunger strike outside the state capitol as they waited for the bill to become law. When they got word that California's governor, Jerry Brown, had, in fact, signed the bill they collapsed into a giant heap, hugging one another as some wept and others shouted cries of relief.

Hernández says she realizes that by telling her story, she has power. She helped change California law.

“I’m proud that women [janitors] are standing up now, aren’t scared,” she says. “It hurts. It makes you angry, but you have to break the silence. You can’t be embarrassed. It’s not your fault. It’s happened to lots of women. Not just one or two, but thousands are behind me, speaking up. Maybe our world as immigrant women will change.”

Lilia Garcia-Brower heads up the Maintenance Cooperation Trust Fund, a watchdog group based in Los Angeles that goes undercover to expose abuse and educate and advocate for janitors. She, too, can’t believe how much has changed for Hernández.

“Looking at Georgina’s trajectory, it’s amazing,” Garcia-Brower says. “It’s all within her. But I believe that with all of these women, it’s all within them. It’s just creating the opportunity for them to come forward.”

Hernández is still working nights and early mornings as a janitor. But now she says she knows her rights, and the self-defense classes have helped her feel like she knows how to fight back. She says the idea is to take what she’s learning to the buildings where women are cleaning and train them during their meal breaks on techniques for protecting themselves.

“Once we teach one of them, it’s like a chain,” Hernández says. “And they all learn their rights and how to defend themselves. To learn how to stay alert if some wolf tries to get close to them.”

She wants people to know that janitors like her have been speaking up long before the #MeToo movement. She says watching women from Hollywood and the corporate world speak up about harassment has been bittersweet.

“I’m sad and angry at the same time,” Hernández says. “Those women have money, they’re powerful, they have everything in life that I don’t have. I’m proud of them for speaking up. But who listened to me? Nobody. These are important women. But I’m important, too.”

Sasha Khokha co-reported “Rape on the Night Shift” with a team from Reveal, the Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California, Berkeley, Univision and FRONTLINE.