10 defining global security questions of 2018

US President Donald Trump and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin shake hands as they meet in Helsinki, Finland, on July 16, 2018. After the leaders held a news conference, accusations against Trump of treason started to fly.

With 2018 behind us, we look back at 10 defining questions in global security that made headlines.

1. What do the North Koreans want?

In January 2018, when North Korea representative Ri Son-gwon shook hands with his South Korean counterpart Cho Myoung-gyon in the demilitarized zone separating the two Koreas, many wondered what this would mean for the two nations technically still at war with each other. One subject the North did not want to talk about was denuclearization. When the South Korean delegation raised the prospect of restarting talks on that issue, Ri was reported to reject it outright.

“We came to this meeting today with a serious and sincere attitude and with the thought of giving our brethren, who have high hopes for this dialogue, invaluable results as the first present of the year,” Ri said.

Related: What it will take to denuclearize North Korea

2. Russia’s shadow armies: Soldiers, mercenaries or volunteers?

In March 2018, we took a close look at how Russia’s involvement in Ukraine and Syria conflicts shows that the Russian definition of “soldier,” “mercenary” and “volunteer” seem to blur when convenient — often at the expense of those doing the fighting, and often to mask the stakes of Russia’s rise as a global power.

Related: A mole among trolls: Inside Russia’s online propaganda machine

3. Activists in Myanmar welcome Zuckerberg’s pledge to clamp down on hate speech. But is it enough?

United Nations officials investigating acts of genocide in Myanmar said in March 2018 that Facebook played a “determining role” in spreading misinformation and hate speech that led to violence. In April, civil society groups in Myanmar say Facebook has routinely been slow to, or outright failed to take down hate speech, as well as “fake news” and misinformation that they say further inflamed already-existing tensions between the country’s Buddhist-majority and Muslim-minority populations. Questions about the company’s role in the ongoing ethnic violence in Myanmar came up during a set of Congressional hearings, organized in response to revelations that the data of as many as 87 million Facebook users was harvested by Cambridge Analytica, a political firm with ties to the Trump campaign.

Related: In Myanmar, fake news spread on Facebook stokes ethnic violence

4. Taxes or violence? Armed group in DRC forces one village to choose

In June 2018, we looked at Democratic Republic of Congo’s layers of strain and instability through the lens of the small village of Miriki that has been controlled for years by an armed group that charges an entrance tax. Anyone who doesn’t have a receipt — proof of payment of about 62 cents each month — isn’t allowed into the village. That’s not the only tax. The armed group, known as Mai Mai Mazembe, also claims portions of harvested crops or charges farmers about 19 cents as they head to their fields. In an area where cash is scarce and incomes are low or nonexistent, the taxes are a needling reminder of rural DRC’s instability.

Related: Congo seeks first democratic transfer of power in presidential election

5. Did Trump commit treason in Helsinki?

In July 2018, when US President Donald Trump and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin shook hands as they met in Helsinki, Finland, accusations against Trump of treason started to fly. But did Trump’s statements in Helsinki warrant the accusation? Perhaps illegal, impeachable, indefensible, a diplomatic disaster, but treason? Republican-turned-Democrat Richard Painter said “the collaboration with the Russians during the campaign, the covering up of the collaboration with the Russians, the obstruction of the Mueller investigation, firing of James Comey, undermining the United States in the face of a foreign adversary” all adds up to “treasonous behavior” but others disagreed short of calling it, perhaps, a betrayal.

Related: Trump’s business history with Russia is a long and colorful one

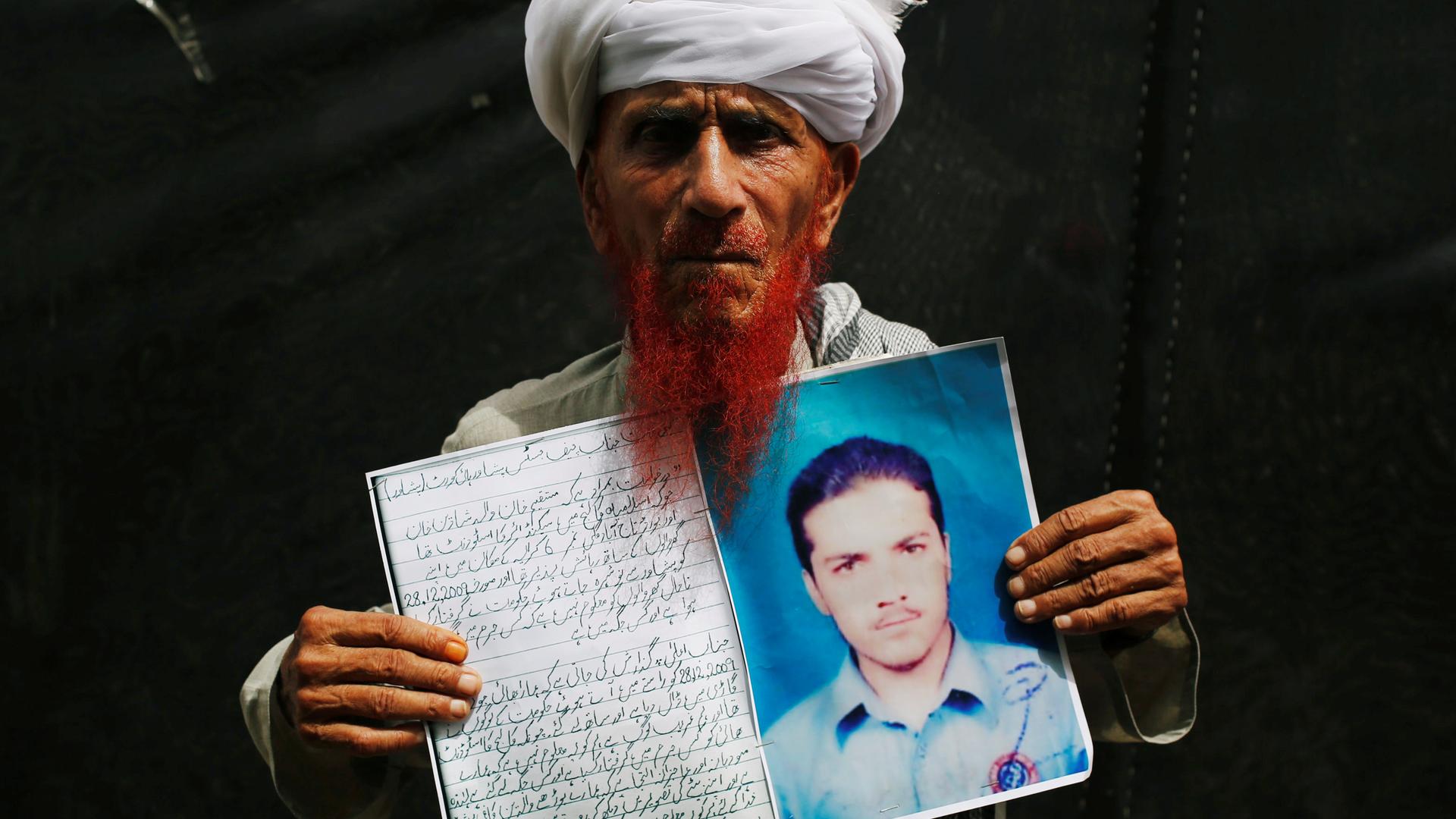

6. Is Pakistan poised for a Pashtun Spring?

In September 2018, we looked into the rising Pashtun movement for equal rights and protections in Pakistan that gave millions of people hope for answers about their missing loved ones. Pashtuns, an ethnic minority group of about 49 million people, often live in remote areas like Waziristan in the west, often battlegrounds between Pakistani troops and Taliban militants — many of whom are also ethnic Pashtuns. Security forces cracked down on their communities and as many as 30,000 thousand people have disappeared. Pakistan took some measures to defuse widespread anger over how the central government has treated the region. But for families with disappeared loved ones, the measures were empty gestures. Loved ones have wondered if they would ever learn where the missing have gone. Authorities refuse to answer inquiries; most say they have hit a brick wall.

7. Why would someone want to kill Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi?

In early October 2018, esteemed Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered when he entered the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, to get marriage documents. For many weeks, Saudi officials rejected responsibility. His death remained a mystery and in many ways, still is. His murder prompted an international outcry to push back on the Saudi-led campaign in Yemen. By December, the US Senate unanimously passed a resolution blaming Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for Khashoggi’s murder, and also made the historic vote to pull out of the Saudi-backed war in Yemen.

Related: US Senate hands Trump historic double rebuke on Saudi Arabia and Yemen

8. Is US policy in Syria driven by politics or emotion?

Back in September 2018, we questioned whether the president’s own emotions and personal interactions played a major role in shaping US policy in Syria. While Trump ran on an anti-interventionist Middle East policy, he simultaneously pushed a hard-line anti-Iran stance that seemed incompatible with promises of limited involvement in Syria and the broader Middle East. Given the sharp turns on Syria already by the Trump administration, unpredictability reigned. By December, Trump had declared victory over ISIS and stated plans to shrink US troops in Syria.

Related: Syrian Kurds left behind as Trump pulls out US troops

9. Will Ukrainians abroad drive change back home?

In November 2018, we looked at mass migration in Ukraine. Ukrainian officials say approximately 6 million people have migrated in recent years. Turbulent times in Ukraine, from independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, to the 2004 and 2014 civil revolutions, to the financial crises of 1998 and 2008, left many Ukrainians financially vulnerable, triggering migration waves. Ukraine now wants to establish a Ministry of Migration to manage the exodus. At the same time, those who have left are beginning to see opportunities to drive change back home.

10. Could decriminalization of Mexico’s poppy farms reduce drug-cartel violence?

In December 2018, we looked at decriminalizing poppy farms in Mexico as a way to reduce catastrophic violence in regions where battles for territory between drug cartels have destroyed communities. The situation is often referred to as the inseguridad or “insecurity.” Poppies are the sole source of income for hundreds of farmers in these small, under-resourced communities. Poppy farming is a crime because the poppies grown are almost exclusively used to harvest their gum to make heroin and trade it over the border in the US. What would it mean to decriminalize Mexico’s poppy farms?