This founding father’s legacy is darker than some Canadians care to remember

John A. Macdonald’s statue is on display in cities across Canada, including this one in Kingston, Ontario’s City Park.

For decades, the American South has debated what to do with statues of Confederate leaders. Now, a similar debate is playing out in Canada over the depiction of one of the nation’s most revered politicians.

“People have to ask themselves a question: ‘What would this place be if there had not been a Sir John A. Macdonald?’” said Warren Everett, president of the Historical Society in Kingston, Ontario, sitting near the city’s 20-foot bronze statue of Sir John A. Macdonald.

Macdonald pioneered Canada’s first transcontinental railway, declared independence from Great Britain in 1861 and served as the nation’s first prime minister for nearly 20 years.

He’s as close to a founding father as Canada has and monuments in his memory are sprinkled across the country. But now Macdonald is being remembered for a more cruel part of his legacy: the infamous residential school system.

The Canadian Parliament, under Macdonald’s leadership, signed The Indian Act in 1876, putting control of Canada’s Indigenous population into the hands of the federal government. A subsequent amendment in 1884 made residential schools a requirement.

The residential school system took Indigenous children from their homes and families and forced them into state-sponsored boarding schools run by Christian missionaries.

“The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change,” Macdonald wrote in 1887.

Investigations have found that children were sexually and physically abused, punished for speaking their native language, even killed.

Natasha Stirrett is Ermenskin-Cree from Alberta. Stirrett’s grandmother was sent to a residential school. She said it’s time to see Macdonald in a new, more honest way.

“You can’t just compartmentalize a person and be like, ‘Well, he was this and that,’” she said. “No. You have to look at him as an entirety.”

A comprehensive report by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2015 found residential schools carried out widespread “cultural genocide,” which the report defines as, “the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group.”

Krista Flute, a Lakota who grew up in Kingston, Ontario, said even that finding isn’t harsh enough.

“They defined it as cultural genocide because that was what was going to make white Canadians comfortable and okay with it,” Flute says. “But under international law, [residential schools are] defined as genocide. Not cultural genocide, just genocide and Canadians need to grip that.”

According to the report by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were sent to residential schools since Macdonald’s time in office and estimated 6,000 children died in the system since it was established more than a century ago.

That history has inspired frequent protests of Macdonald’s legacy all across Canada. One of his statues was vandalized in Montreal in August.

In Victoria, British Columbia, local officials took down Macdonald’s statue outside city hall this summer. It’s expected to be moved to another public space in the city.

The debate is even more complicated in Kingston, where Macdonald grew up and got his start in politics. His name is on a local school, a busy city street, and up until this year, a popular downtown pub.

Owner Paul Fortier changed the name of that pub from “Sir John’s Public House” to “The Public House” in January. Fortier told the CBC, “I could understand the hurt that it caused. We don’t want to create a feeling of alienation to any customers.”

But Fortier said it led to a vicious and unexpected backlash.

“I was receiving death threats,” Fortier said. “Overnight, there would be people who would phone and leave messages on the answering service saying, ‘look out,’ ‘watch your back,’ ‘you’re going to be a goner.’”

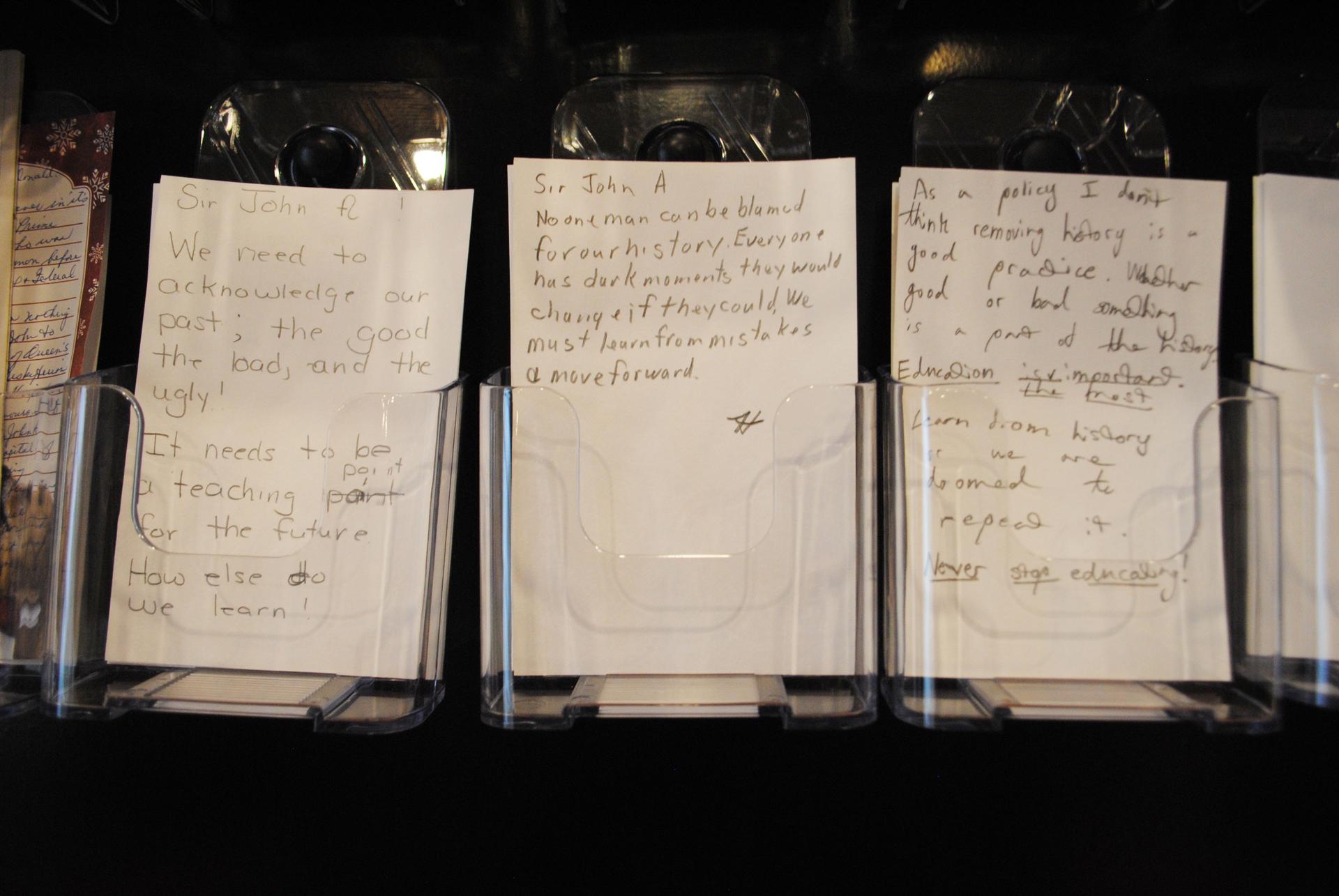

If you take a statue down or remove Macdonald’s name, some in Kingston see that as a betrayal of Canada’s history. If you leave it up, keep everything as is, others will tell you that’s an insult, a cover-up.

“Trying to extinguish history by taking down the statue would not serve the purpose of expanding people’s knowledge of the full story and the pain and suffering caused to Canada’s first nations by one of the Fathers of Confederation,” one online comment reads.

Jennifer Campbell, who is the manager of Cultural Heritage for the city of Kingston, said it is not her intention to erase history.

“It’s about adding to history and framing histories in ways that they tell more inclusive stories,” Campbell said.

The city has been taking comments for months and is planning community forums this spring to discuss how to better tell the city’s history, including Macdonald’s legacy.

As for Natasha Stirrett, whose grandmother was sent to a residential school, she said any potential compromise is a copout.

“On the surface, Canada wants to seem like it works with Indigenous people. Canada wants to seem like it recognizes Indigenous sovereignty and nationhood,” Stirrett said. “But we know different.”

The impact of Macdonald’s policies, Stirrett says, is still unfolding. There are higher rates of poverty and lower rates of employment among Canada’s Indigenous.

Battles continue over land rights and access to natural resources.

And the trauma of the residential schools is still fresh. The last one didn’t close until 1996.