This historian’s new book on Mexican migration is perfectly timed

A newly built section of the US-Mexico border fence is photographed in April from the outskirts of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

Ana Raquel Minian grew up in Mexico City where, at home, “politics was discussed at the dinner table pretty much every day,” she says.

But to learn more about her own country, she decided to study its ties to the US. She started digging, studying history in the United States, earning her doctorate at Yale University. Now, after a decade of research, she’s published her new book, “Undocumented Lives: The Untold Story of Mexican Migration.”

It’s hard to imagine a better time for her work to come out.

“Undocumented Lives” is a deep dive into the history of Mexican migration to and from the United States and how, many times, migrants can feel ni aquí, ni allá, neither here, nor there — not fully recognized by any one place. It’s a perspective that Minian heard many times from the hundreds of people she interviewed, a feeling hardened by policies in both Mexico and the US that, she argues, excluded or ignored the economic realities faced by migrants.

Minian, a Stanford University history professor, begins her book in 1965, a year after the United States ends the bracero program, a government temporary-worker program aimed at filling labor shortages during World War II, when many American men left to fight abroad.

“The United States needed more people working in the United States, and one of the ways that it found their manpower was by bringing Mexicans to work in the fields,” Minian says.

Yet when the bracero program ended in 1964, people from Mexico still wanted to work in the US — people like Gregorio Casillas, who Minian interviewed for her book. Casillas was born in a small rancho in the north-central Mexican state of Zacatecas. He saw his father go to the US as part of the program in the 1950s and decided to join him.

“But when the bracero program ended, Casillas knew that he had to come here without papers,” Minian says.

Like many migrants from Mexico, he worked in the fields but then changed jobs. He became a carpenter, allowing him to earn more, and began sending more money back home.

Yet Minian was struck by how silent politicians in Mexico were when it came to undocumented migration — men, especially, leaving the country — increasingly in the 1970s and especially in the late 1980s.

“When the problem of undocumented migration really starts in the 1970s, there was, in some ways, an active role of the Mexican government of not speaking about the issue of migration because they knew that this was an embarrassment,” Minian says. “Government officials knew that the large numbers of people who were having to go to a place where they were considered illegal meant that Mexico was failing to incorporate them.”

Mexico took an “active policy of silence” while Mexicans in the US sent billions home to support their families and towns. And that official silence in Mexico continued, Minian documents, though the late 1980s and beyond, including while the US tightened immigration laws and its Southern border.

However, fewer migrants risked going back to the US, only to have to cross an increasingly sealed-off border.

“Instead they settle permanently here without papers,” says Minian. “Not only that, but they encourage their wives and their children who previously had not, for the most part, migrated, to move north and remain here with them without papers.”

Minian titles one book chapter “The Cage of Gold,” after the song “La Jaula del Oro” from the norteño band Los Tigres del Norte.

“The song talks about this migrant who is living in the United States and dreams of going back to Mexico but feels entrapped, like in a cage, that yes, is made of gold, but he can’t leave this country,” Minian says. It also references the children of migrants who were born or raised in the US and do not want to return to Mexico.

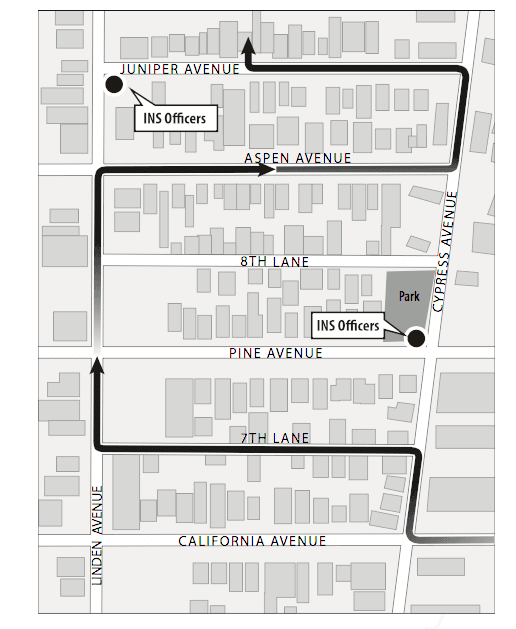

Minian also documents how some migrants began to change their movements in a more policed America.

“For example, they knew that immigration officials would often be at a particular park, and even if it meant walking many more blocks, they would take a very circuitous way back home in order to avoid bumping into these immigration officials,” she says.

It’s a reality still true for many immigrants in the US today.

As Minian wrapped her book, Donald Trump campaigned for the presidency, often casting Mexican nationals as criminals and as people driving unauthorized migration to levels that were “beyond belief,” when, in fact, significantly fewer Mexicans were crossing the US-Mexico border.

For Minian, “pejorative stereotypes about Mexican migrants had helped determine the US presidency.”

What’s more, she says, Trump’s rhetoric spoke of a “population of individuals who I had interviewed personally, who had come to work, who had made some mistakes like everyone, who had fallen in love, out of love, had sent money back to Mexico to build their hometown, and that all of this nuance of humanity was being lost by accusations of ‘they’re rapists’ or ‘they’re bad hombres.’”