Hundreds of thousands of displaced Ethiopians are caught between ethnic violence and shadowy politics

At a camp for displaced Ethiopians outside Dire Dawa, it's claimed that this Somali boy lost the sight in his left eye after Oromo police threw a rock that hit him in the face. Ethiopia is experiencing one of its worst population displacements due to violence in decades, as conflict between ethnic Somali and Oromo has led to clashes and forced evictions.

Turning sideward, a displaced Ethiopian woman lifts the hem of her dress to reveal scars running up her leg — shrapnel wounds from the grenade she says local police tossed at her and three other women.

“We’d always lived with the Oromo peacefully until the [Oromia] regional special police turned up and started burning the houses of Somali,” says the woman, an ethnic Somali, one of Ethiopia’s five main ethnolinguistic groups. “I ran to the local police station with three other women, but the police told us: This is not the day when Somali are protected.”

As the women turned to flee the grenade was thrown, she says. She was wounded in her leg and managed to stagger on after the explosion and escape, but she doesn’t know what happened to the other women. She says she thinks they were caught.

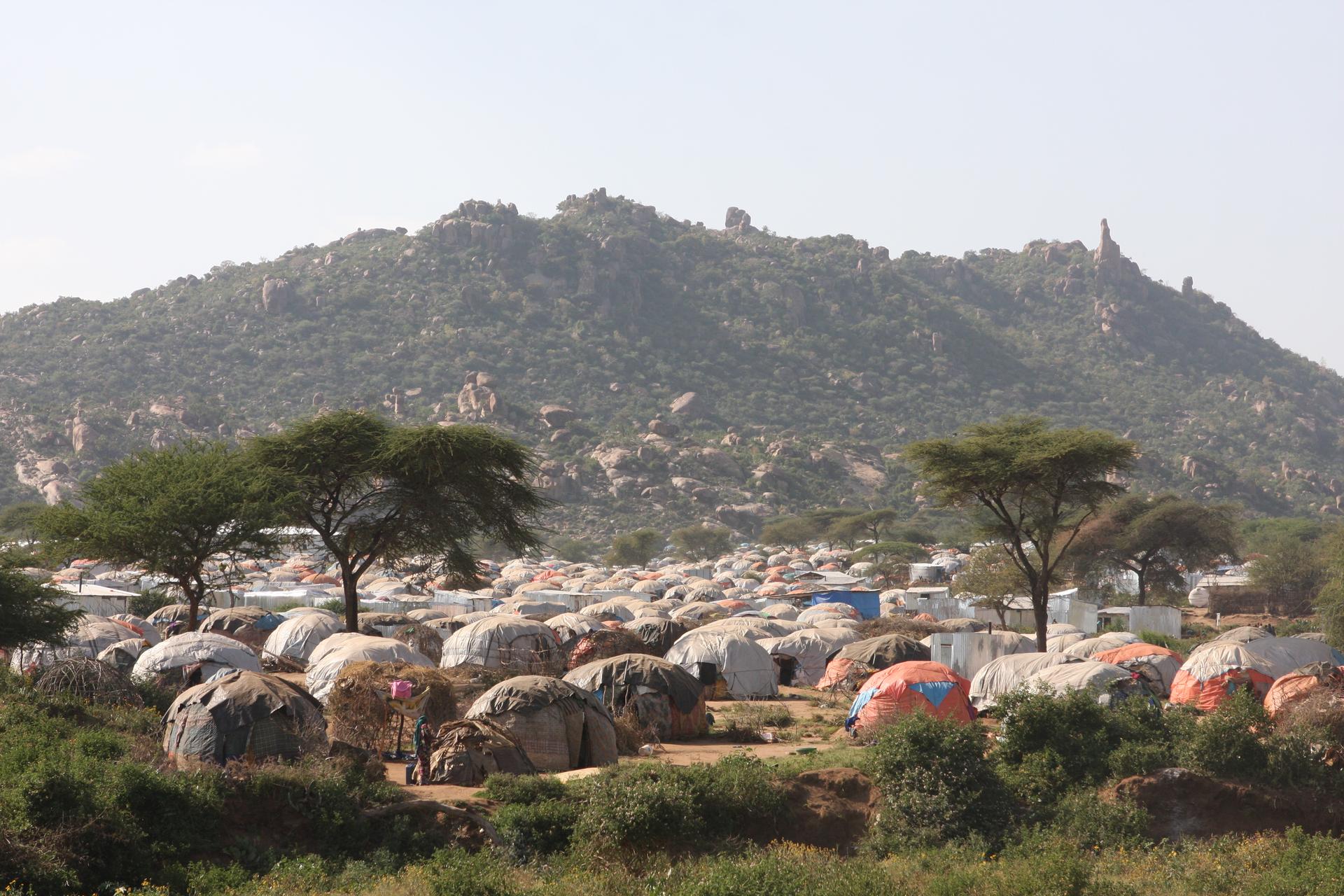

You’ll hear many stories like hers, as well as reports of rape and pregnant women miscarrying while being evicted in overcrowded trucks, at a camp in the lee of the Kolenchi hills in eastern Ethiopia’s Somali region. There, thousands of Somali displaced by recent ethnic violence in the neighboring Oromia region are now sheltering.

Tit-for-tat evictions and violence have also displaced Oromo. An estimated 50,000 Oromo have been forced to leave the Somali region. Many of them are stuck in camps, too. Like the Somali, they tell stories of police violence (in their case by Somali regional police), reveal physical wounds and describe communities coming apart at the seams.

“The mother was a Somali married to an Oromo,” says Fatima, holding a child that was dumped at her house before she was evicted with other Oromo from Jijiga, the capital of the Somali region. Along with her own three children, she is at a camp for displaced Oromo outside the eastern city of Harar, near the fractious regional border.

Other women at the camp have lost children and husbands. One woman lies on the ground beneath a blanket in the middle of the day. People try to comfort her, but she is immovable with grief — she knows nothing of the condition or whereabouts of her four children.

Estimates of the total number of Oromo and Somali displaced range from 200,000, according to local media, to 400,000, according to some humanitarian workers on the ground, making this the largest displacement of Ethiopians by violence since the 1991 revolution and preceding civil war.

What led to such strife in the two regions, and in previously tightly knit communities, some of which had integrated peacefully for centuries and in which intermarriage was the norm?

There are at least two sides to the story.

One explanation points to tension erupting after Somali police reportedly arrested two Oromo officials near the contested regional border. When the officials were then alleged to have turned up dead — some details of when and why are hazy — it helped spark Oromo protests that turned into rioting on Sept. 12 in the city of Aweday, leaving at least 18 dead. Most of those killed were Somali traders.

Those Somali had relatives back in the Somali region, resulting in the Somali regional government evicting Oromo. Somali officials say the evictions were necessary to protect Oromo from reprisal attacks. This then led to evictions of Somali from Oromia.

Then there is the ongoing drought — particularly hitting eastern Ethiopia — which puts further pressure on pastureland and resources, thereby adding to tensions.

“As you move west of the regional border the land becomes higher with more water and pasture, a factor the drought exacerbates,” says the head of a humanitarian organization in Ethiopia who spoke on condition of anonymity due to problems his organization has had working in the Somali region. “So where the regional border runs is very contentious — you’ll find different maps giving a different border in each of the regions.”

But the other side of events is far more opaque. Some claim that the reported killings of the Oromo officials were a fabrication to foment unrest. Others question how such a bloody riot could occur in a previously peaceful city known for its vibrant trade and far removed from the border, where ethnic tensions usually occur.

Meanwhile, displaced Oromo and Somali claim the respective regional police forces are responsible for much of the violence. And they say the violence is being directed from the top.

Both sides accuse politicians at the regional and federal levels of leveraging unrest to strengthen support for their parties, settle vendettas and divide and rule — all of which have long track records in Ethiopian politics.

The Ethiopian government has deployed federal forces to try to secure order and pledged that everyone can return to their homes, as is their right under the federal constitution. But achieving that anytime soon looks unlikely, needing the cooperation of two regions in conflict.

“This is still a rising curve and not a descending curve,” says a member of an international organization in Ethiopia monitoring displacement who spoke on condition of anonymity out of concern that commenting publicly could hurt his group’s ability to operate in the region.

These ethnic clashes follow more than a year of protests by the Oromo against the federal government over corruption allegations, land appropriation and civil liberties, leading the government to declare a state of emergency that only ended in August.

As a result, there is no love lost between the federal government and the Oromo. Meanwhile, the federal government relies on the Somali regional government to secure the country’s vulnerable eastern border against infiltration by al-Shabab from Somalia, which it has managed effectively so far.

Such tensions and dependencies generate suspicions and accusations about the government’s real intentions, amid equally unclear motivations and ambitions of regional governments — as well as influences beyond Ethiopia’s borders.

Displaced Somali and their regional government officials are particularly critical of external influence from Ethiopia’s large US-based diaspora, accusing Oromo social media activists of stoking trouble.

“The real Oromo administration is not in this country — it is outside,” says an old man at the Kolenchi camp who fled Ethiopia’s Bale zone in the south after attacks and looting by Oromo militia. “They are the troublemakers.”

All the while, and as throughout the country’s history, it is ordinary Ethiopians, regardless of ethnicity, who are bearing the fallout from what appears a combination of longstanding grievances erupting and shadowy political machinations, as different interest groups jostle for power in Ethiopia, seemingly without regard for the human cost.

Ethiopia is certainly not unique in that respect — though observers note the colossal amounts of financial aid from the likes of the US and UK might be leveraged to push for solutions and answers sooner rather than later.

“The dead are gone, nothing can be done for them,” says another Somali man at the Kolenchi camp. “But there are children left behind and people still being held in Oromia jails.”

James Jeffrey reported from Kolenchi, Ethiopia.