Can virtual reality change how people respond to war reporting? One photojournalist is trying to find out.

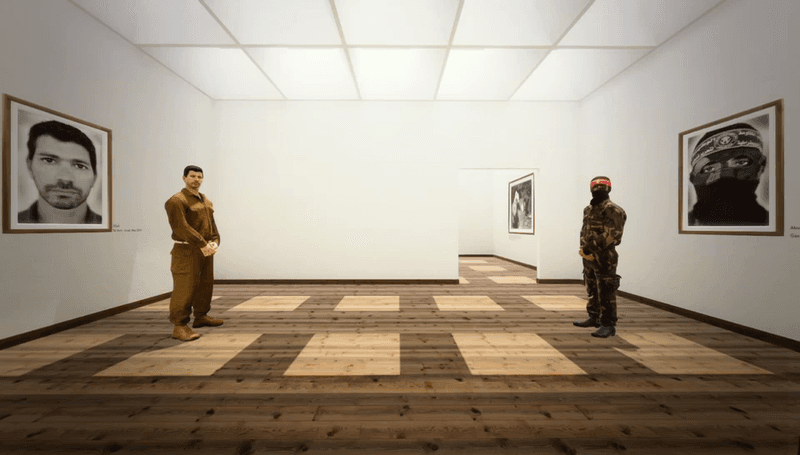

Inside the virtual reality exhibition "The Enemy," an Israeli soldier and Palestinian fighter stand on opposite sides of the room in front of their portraits.

As a photojournalist, Karim Ben Khelifa has been on the frontlines of wars and international conflicts — including in Iraq and Afghanistan — observing and documenting them through his camera lens.

But in recent years, Khelifa found himself facing a sort of existential crisis, questioning whether his photographs conveyed the reality he was experiencing on the ground.

“I was frustrated with what I was doing as a war correspondent — trying to really be the witness of what was happening on the edge of those conflicts,” Khelifa said.

“What is the point of images of war if they don’t change people’s attitudes towards armed conflicts, violence and the suffering they produce?” Khelifa began asking himself. “What is the point if they don’t change anyone’s mind? What is the point if they don’t help create peace?”

In exploring those questions, Khelifa’s work has taken a turn into the virtual world.

"When I discovered virtual reality I just wondered: what happen[s] if I bring it to journalism? What happen[s] to the audience?”

Khelifa's putting those questions to the test through "The Enemy," an interactive virtual reality installation that explores three international political conflicts — one each from the Middle East, Africa and Central America — through virtual reality and 3D reconstruction.

I went to experience the exhibition at the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where it’s on view through December 31.

To enter this virtual world, I first have to put on some equipment: a backpack containing a battery and a computer, as well as an Oculus Rift virtual reality headset.

And just like that, the large room I’ve been standing in — the gray walls — it’s all transformed into a bright room that resembles other gallery spaces I’ve visited in the past.

The walls are white. I can see other rooms in the distance. A message written on the wall in front of me reveals the conflict I’ll be exploring in this room.

“Within the borders of Israel and Palestine, today 12 million people are directly affected by the conflict. More than 51,000 men, women, and children have lost their lives violently since 1948 and approximately 163,000 people have been injured,” the message reads. “The dispute over this land is almost a century old.”

Two black and white photographs — captured by Khelifa — hang on opposite sides of the room.

The first is of a military tent between Jerusalem and the West Bank. A handful of Israeli soldiers sit underneath, taking shelter, an Israeli flag waving in the distance.

The second photograph, on the opposite side of the room, is of a young Palestinian throwing stones at an Israeli military outpost.

Then, suddenly, the photographs fade off the walls.

Remember, this is virtual reality.

In their place, two portraits — also black and white — fade in.

Khelifa tells me in a recorded message that one is of a Palestinian fighter, Abu Khaled. I learn that he’s 29. He has two children and worries about their future. He no longer sees a point in the contentious conflict, Khelifa explains.

The second photograph is of an Israeli soldier named Gilad. He’s a tattoo artist, and also has two children, Khelifa tells me.

When the narration ends, I hear footsteps. I turn around and watch as the two combatants — well, 360-degree renderings of the combatants — walk into the room.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DlIyPF7hudX0

Gilad and Abu Khaled stand in front of their portraits, on opposite sides of the room.

I watch them from the middle.

I can tell they're not real.

But their movements and expressions feel so human. It’s unsettling.

Gilad, the Israeli soldier, calls me over.

He's in his khaki uniform, his hands crossed in front of him.

When I get close enough, Gilad greets me. For the next few minutes, I listen to a recording of the photographer asking Gilad a set of questions.

“Gilad, who is your enemy?” Khelifa asks. “And why? Did you ever kill your enemy? What is violence for you? And what is peace for you?”

When asked where he sees himself in 20 years, Gilad responds: “Twenty years from now, I wish to see myself accompanying my little girl to her graduation from the university instead of the ceremony discharging her from the military.”

As he speaks, Gilad gestures with his hands. He makes and breaks eye contact. And he keeps me engaged in a way his portrait — right behind him — didn’t.

When the conversation ends I walk to the opposite side of the room where Abu Khaled, a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, waits for me.

He’s wearing camouflage and a mask covering his face. He, too, answers the same set of questions.

“Abu Khaled, where do you see yourself 20 years from now?” Khelifa asks.

“Regarding my personal experience, I have been through extremely painful situations,” Abu Khaled says. “Twenty-three members of my family passed away. They died a martyr’s death, including my grandfather, my uncles and children — eight kids of my family. I have also been severely injured during Israeli occupation, and they’ve destroyed my home. After all that, I still believe in hoping for a peace that ensures a decent living and a free life inside Palestine."

When the interviews are over, the two men turn to leave.

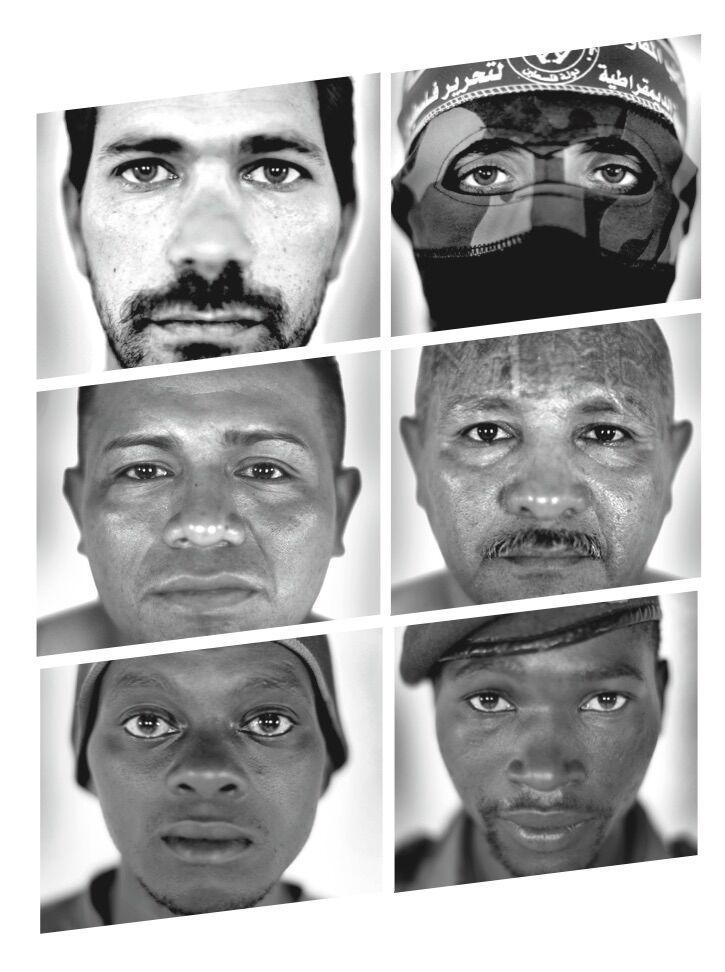

In the next two virtual rooms, I meet combatants involved in other international conflicts: Fighters from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and members of two competing gangs from El Salvador.

Some are shirtless. I can see their tattoos, the reds of their eyes, their chests moving as they breath. It all feels so human.

Khelifa hopes that meeting these combatants — even in this virtual form — will grab people and help them listen more deeply.

But it’s not just about the experience. After I go through the installation, Khelifa tells me that in re-imagining his work, he’s grappled with another big question.

“Who do I actually want to talk to? Who's my target audience for this work?” Khelifa told me he’s had to ask himself. “And the primary target audience is to get to the next generation of fighters. The people who have been told the story about the other, who are in this process of dehumanization because there is no meeting point humans in these places for understanding each other and the communality of each other."

Khelifa’s working to bring the exhibition to the Middle East, as well as Africa and Central America, and he has had one showing in Tel Aviv, over the summer.

“Israeli or Palestinian audiences had to walk towards the enemy,” Khelifa said when recounting the interactive installation’s reception at the Tel Aviv International Student Film Festival. “[That’s] not something they do in real life. They would actually do the opposite. But here they're safe. That doesn't mean it works nicely and comfortably. They go with fear, they go with apprehension, they go with a number of stereotypes. But it's a good way to challenge that.”

And while some audiences in the US, where the exhibition is currently on display, may not be Khelifa's primary target, he says there's still much to take away from the exhibition.

“I’m not telling who’s right, who’s wrong” Khelifa explained. “I’m not telling you what to think. … I’m asking you to rethink the relationship to the other when you see people that have been designed and trained to kill each other.”

Will it work? Will it bring “conceptual change or real impact?” Khelifa asks. “We need more time to find out.”