How Harvey Weinstein used nondisclosure agreements to silence his accusers

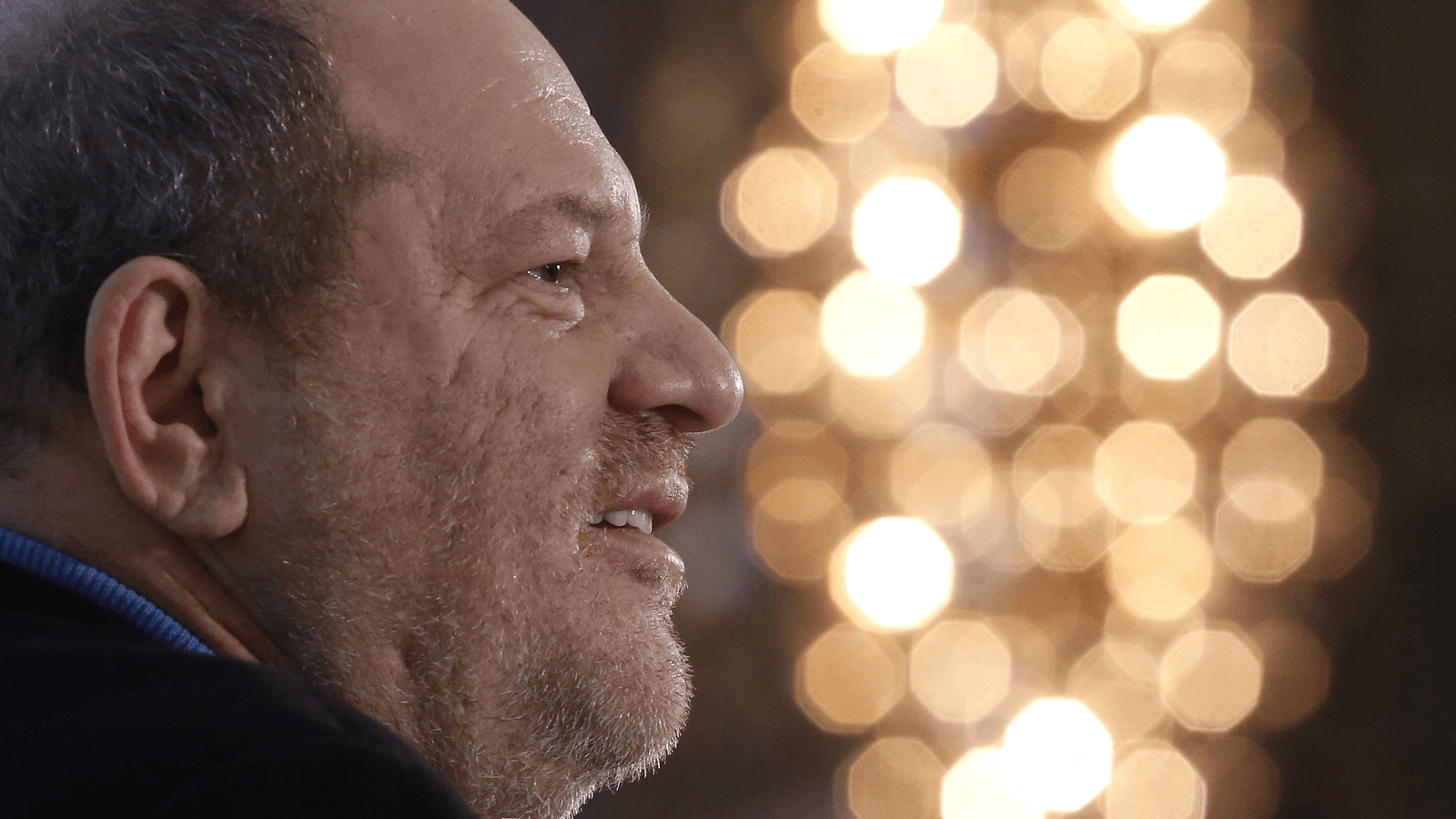

Harvey Weinstein speaks at the UBS 40th Annual Global Media and Communications Conference in New York, Dec. 5, 2012.

How did he get away with it for so long?

It's a question many have been asking in the aftermath of the Harvey Weinstein scandal, as the number of women accusing the disgraced movie mogul of acts ranging from sexual assault to rape approaches 50.

Like former Fox News star anchor Bill O'Reilly and legendary comedian Bill Cosby before him, the answer lies in the murky world of nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) and out-of-court settlements, which, critics argue, perpetuate abuse by allowing it to remain in the shadows.

In Weinstein's case, "clearly, they played a very large role as it turns out that there have been dozens of settlements in which women who might have brought sexual harassment lawsuits or might have spoken out publicly have signed these agreements," said Ariela Gross, a law professor at the University of Southern California.

Many victims received large sums of money in exchange for their silence, according to Zelda Perkins, one of Weinstein's former assistants, who broke her agreement in an interview with the Financial Times.

"I want to publicly break my nondisclosure agreement," she told the paper. "Unless somebody does this, there won't be a debate about how egregious these agreements are and the amount of duress that victims are put under."

And last week, 30 employees of the Weinstein Company founded by the producer and his brother Bob penned an open letter acknowledging they may be breaching their confidentiality agreements but still wanted to defend themselves from claims they knew he was a "serial sexual predator."

David and Goliath

Confidentiality agreements have increasingly become a standardized part of many employment contracts — and even agreements between companies and consumers.

There are some uncontroversial uses, such as when a firm wants to guard its research or industrial secrets. Some victims of harassment, meanwhile, prefer not to have their cases come out in the open.

But all too often, say experts, such clauses favor abusive employers, allowing them to censor and threaten their workers with impunity.

When an agreement gets handed to a new employee along with their job offer, many feel they have no choice but to sign it, or else lose the position.

Perkins, who said she had endured several years of harassment by Weinstein but was driven to quit after a female colleague said she was assaulted by him, recounted several punishing late-night sessions with the producer's army of lawyers that finally resulted in her settlement.

"I thought the law was there to protect those who abided by it," she said, adding: "I discovered that it had nothing to do with right and wrong, and everything to do with money and power."

Beginning of the end?

For employment lawyer Genie Harrison, NDAs are "part of the fleecing of America, robbing citizens of their power," adding that their legality has been validated by no less an authority than the US Supreme Court.

There are, however, some limits — they do not apply to government entities. The public has a right to know, for example, if the city of Los Angeles reaches a settlement with a citizen.

Confidentiality agreements can also be broken if a witness is called to testify in a trial.

TV legend Bill Cosby, who was accused by more than 50 women of sexual misconduct still sued one of his accusers on the basis that as a Canadian citizen she fell out of the purview of the US legal system.

The courts are entitled to override clauses deemed immoral or excessive ("unconscionable," in legal parlance). Provisions that protect whistleblowers may also apply in some cases.

Gross, the law professor, argued that the spotlight shone by the Weinstein affair on sexual harassment may signal the beginning of the end for NDAs.

Just as "it might be in the public in interest to say 'Hey, my employer is polluting rivers,' … some people say it might be in the public interest to know 'Hey, my employers have been groping young women,'" Gross said.

AFP's Veronique Dupont reported from Los Angeles.