The work of Ramón Esono Ebalé at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum.

Dictators aren't known for their sense of humor. At least when the jokes are about them.

Ramón Esono Ebalé, a cartoonist from the tiny West African country of Equatorial Guinea, found that out recently. He was arrested on Sept. 16 during a visit to Malabo, the country's capital.

The target of Esono's cartoons is the country's long-time leader, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who has ruled Equatorial Guinea with an iron fist since overthrowing his own uncle in a coup in 1979. Governing in Equatorial Guinea has been an Obiang family business — an often ruthless one — since independence in 1968.

"[Obiang's] family basically controls all important sectors of the economy," says journalist Rowan Moore Gerety, who has written about Esono's tireless efforts to use cartoons to unseat the dictatorship in Equatorial Guinea. The title of his article says it all: Comics Without Captions: Can a cartoonist help unseat a dictator?

Equatorial Guinea was the ultimate backwater until it struck oil in the 1990s. Now it's Africa's third largest producer. The oil money rolls in to the government but doesn't get reinvested in the people.

"[Equatorial Guinea] is a very important oil producer," says Moore Gerety. "It's about 95 or 98 percent of the economy and really most people there don't touch any of it."

A 2017 Human Rights Watch report said that "mismanagement of its oil wealth has contributed to chronic underfunding of its public health and education systems in violation of its human rights obligations."

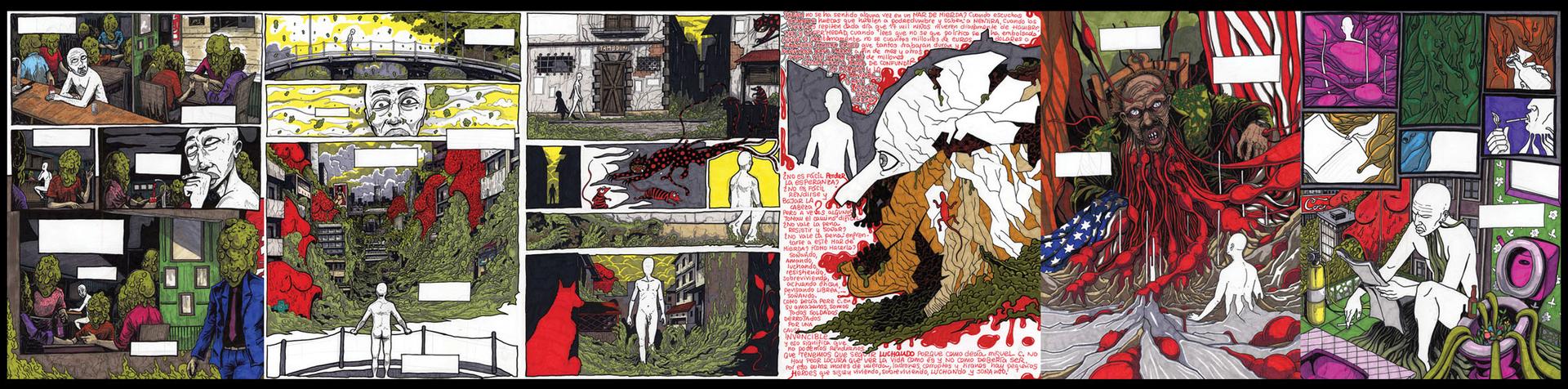

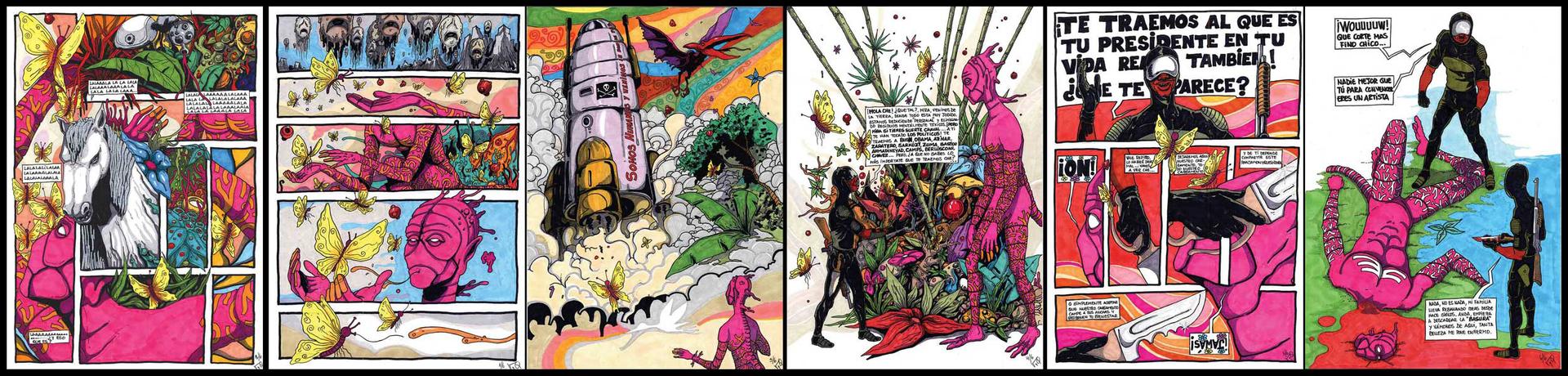

Esono, known by his pen name, Jamón y Queso, uses his drawings to expose the gross inequality in Equatorial Guinea. His images are often crude and outrageous and his focus is squarely on President Obiang and his repressive leadership. And that is exactly what Esono has come up against.

"They have a very active secret police and they really don't tolerate any dissidents," says Moore Gerety. "People who speak out are either imprisoned or very quickly find a way to get out of the country." Esono has now experienced both fates.

When he first started exhibiting his cartoons in Equatorial Guinea in the mid-2000s, Esono felt the sting of censorship. It wasn't coming from government censors but exhibit organizers who worried about the words Esono was putting in his cartoon characters speech balloons. His response: Leave the speech balloons empty, an apt metaphor for the state of freedom of speech in Equatorial Guinea.

In 2011, Ramón Esono Ebalé left Equatorial Guinea to conduct his cartoon activism from Paraguay (he was on a visit home to Equatorial Guinea to renew his passport when he was arrested on Sept. 16). Moore Gerety says being in exile has unleashed Esono as an artist and he's an internet star. But his reach into Equatorial Guinea is limited.

"Equitorial Guinea is not a country where you just get on the internet easily wherever you are. [Esono's] web sites are censored. There are people who work in government, apparently who have some way of getting around it and so there's some irony in the fact that maybe some of his most loyal readers are actually members of the regime."

And that direct link from his artistic imagination to the government elite of Equatorial Guinea may be why Esono was arrested.

In 2014, Ramón Esono Ebalé published a graphic novel, "La Pesadilla de Obi," or "Obi's Nightmare." The premise of "Obi's Nightmare" began with a question: What would be the worst possible fate to befall Equatorial Guinea's leader, Teodoro Obiang? Moore Gerety says the answer was obvious.

"It imagines Teodoro Obiang the president waking up one morning and discovering that he is just another lowly resident … living in a shack that leaks without any running water with an angry wife who sends him out to sort of face the indignities of the market. He goes on this sort of awful day-long adventure where he ends up in jail and goes through all of these terrible things that a normal citizen might have to go through in the course of daily life there."

Esono has been on a quest to get the Spanish edition of Obi's Nightmare, La Pesadilla de Obi, into the hands of the citizens of Equatorial Guinea. He's been relying on a network of individuals inside Equatorial Guinea to hand deliver hard copies. Perhaps it got into the wrong hands.

Moore Gerety says Esono is being held at a notorious prison called Black Beach in Equatorial Guinea's capital, Malabo.

"It was pretty notorious after independence [in 1968] as the main place that political prisoners were sent. Torture was commonplace and even today there are reports of inmates being denied medical treatment and being denied food."

Moore Gerety says Esono is not likely to see a courtroom. It's a political case.

"The sense I've gotten is that what the Obiang regime is waiting for is some kind of full-throated apology which even if it isn't really credible, would at least be viewed as kind of a victory."

There are examples from the past where opposition politicians have been made to put T-shirts with the president's face on them and go on national television renouncing what they had said earlier.

"I think that serves kind of a dual purpose both to get the apology on its own and on the other hand, it kind of underlines the power that Obiang has to enforce his will even on his harshest critics," he says.

But Moore Gerety says Esono is passionate and committed and isn't sure he's ready to mouth an apology, even it means his release.

"He really would be loathe to do something like that and would fight it with every ounce of his being."