Bringing the world into focus for some of the 2 billion people globally who need glasses but don’t have them

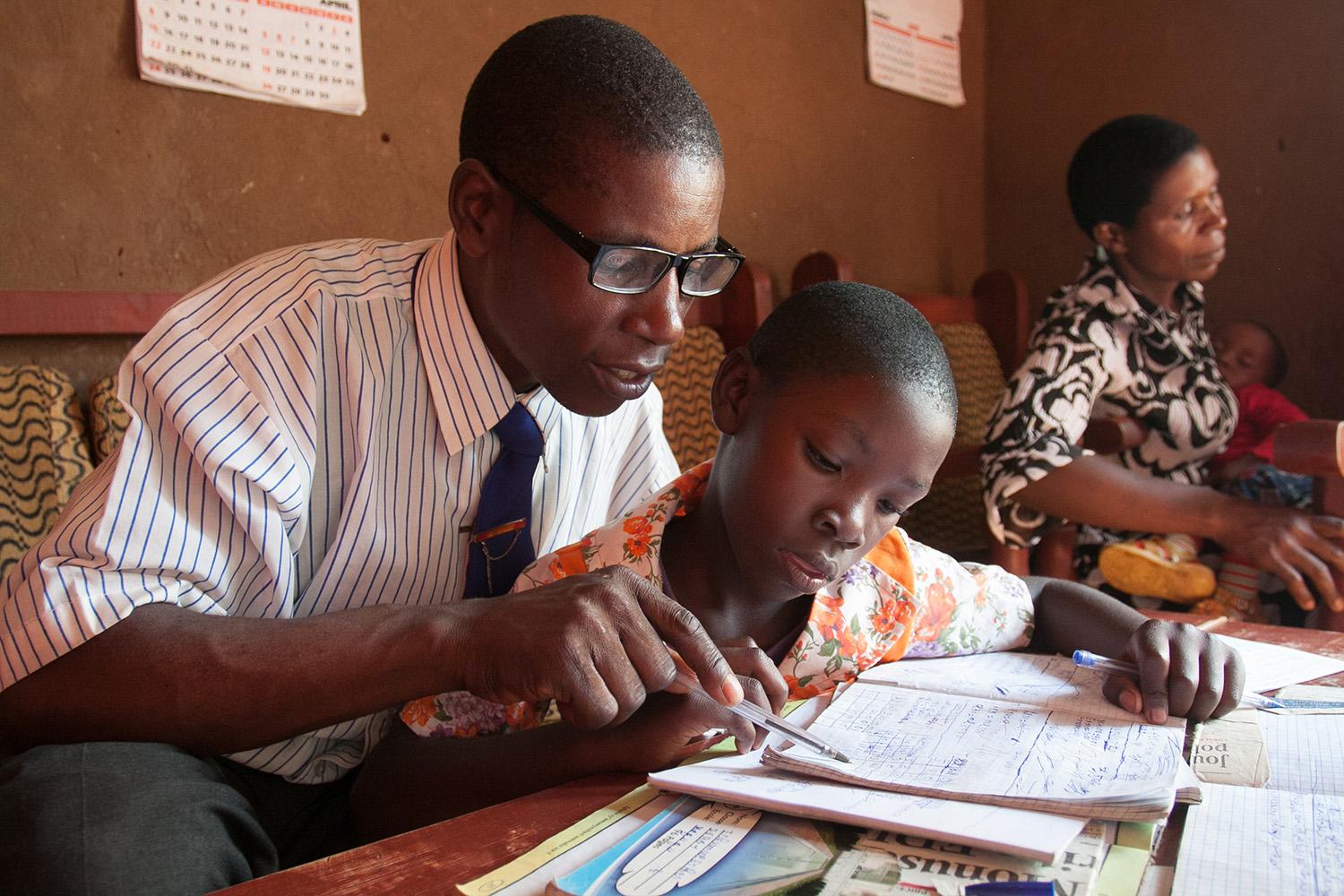

Vision test, as part of VisionSpring's efforts to reach people in remote areas who need glasses.

Of the many things we take for granted, being able to see is right up there. It’s fundamental to how most of us learn and bond, work and play, and navigate the world.

We also take for granted that if the world grows fuzzy, there’s an easy and accessible fix for that — glasses, contacts or laser surgery. In fact, most people in the world need glasses at some point in their lives.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

But in developing countries, by some estimates, some two billion people don’t have access to the glasses they need. They can’t afford them, or optometrists are scarce, or both.

“This is not just a health issue,” says Jordan Kassalow, an optometrist who founded VisionSpring, a global social enterprise focused on selling affordable eyeglasses to people who make less than $4 a day. “This is a global development issue.”

The lost productivity from people who need glasses but don’t have them, Kassalow says, drags down the global economy by more than $220 billion each year.

And yet, as global development issues go, this one hasn’t been getting the focus it could. Kassalow says total funding to initiatives to get glasses to people in developing countries who need them was about $38 million last year — compared to the billions of dollars that go each year to other key issues, like providing energy and clean water.

“And we know the solution. It’s a 700-year-old technology,” Kassalow says. “It’s just about distribution and demand creation. … Some people who need glasses don’t know they need glasses until they put them on, and suddenly they see individual leaves of trees, rather than a big green blob.”

It’s not that vision has been entirely ignored, as a development issue, says Ella Gudnow, VisionSpring’s president.

“But much of the eye research and eyecare has been focused on blindness and not refractive error, and not vision impairment,” she says. “It’s really been focused on cataracts, glaucoma and river blindness. So many organizations are now paying more attention to refractive error. … We’re a little unique in that we take the social enterprise approach — getting radically affordable eyeglasses out to people who make less than $4 a day.”

“We had one woman, and I love this story, her name was Rama Devi, and she was a natural saleswoman,” says Kassalow. “She came to us and said she wanted more territory, and she bought a motorcycle so she could expand her territory. And because it wasn’t considered appropriate for a woman to go alone into new villages, she hired her husband as her driver. So not only did her husband support her, he was her first employee.”

There are still some cultural barriers, in southern Asia and elsewhere, to women getting eyeglasses.

“In India, research has shown that 71 percent of girls of marriageable age will feel they are less marriageable if they wear glasses,” Kassalow says. “And in some societies, when kids start wearing glasses, their elderly grandparents will say those are for rich people, not for village boys or girls.”

In some places, he says, there’s even a belief that wearing glasses makes your eyes worse.

Still, VisionSpring, working with local partners, has already sold 3.7 million pairs of eyeglasses in such countries as India, Bangladesh, Kenya, Rwanda and Nigeria.

The idea in selling them — usually for $1 to $3 for a pair for reading glasses, a bit more for prescription glasses — is that people will value them more.

“And it also makes us better at what we do,” says Kassalow, because it makes VisionSpring work harder to make sure it’s providing styles and quality that people want. “Just because people are poor doesn’t mean they deserve second rate products. And, we believe that vanity is not monopolized by rich people. No matter where you live or how much you make, you care about how you look.”

A case in point, Kassalow says, drove the point home to him when he was a student working with a vision clinic in western Colombia, and a Choco Indian named Noko canoed a whole day down river, because she’d heard that American eyedoctors might be able to help her.

“She was known as the blind lady in the village,” Kassalow says. “And when we examined her eyes we understood why. She had a -8 prescription; she couldn't see the big E on the chart. And we gave her her first pair of glasses and she saw 20/20 in an instant. And we were all very proud of ourselves — we gave ourselves high fives. And she went back up river.

A few days later, Noko was back. She said the other villagers were making fun of her glasses, and she wanted a different pair.

“We didn’t have another pair that matched her prescription, but her complaint was quite valid,” Kassalow chuckles. “Because, the one pair of glasses we’d had that matched her prescription was a pair of 1950s cat-eye glasses with rhinestones. They might have looked cool in the East Village of New York, but they didn’t go over so well in her village.”

Recommended further reading:

Eyeglasses for Global Development: Bridging the Visual Divide, by the Eyelliance, published by the World Economic Forum, July 2016.

The myopia boom. Nature, March 18, 2015.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)