The incredible story of Italian cyclist Gino Bartali, who risked his life to rescue Jews during the Holocaust

Cyclist Gino Bartali used training as a cover for secret efforts to rescue Jews.

One of the great cycling races, the Giro d'Italia, or Tour of Italy, concludes its 100th edition on Sunday in Milan.

Riders race across the island of Sicily, cross over to the mainland and then follow Italy's boot from the heel to the top.

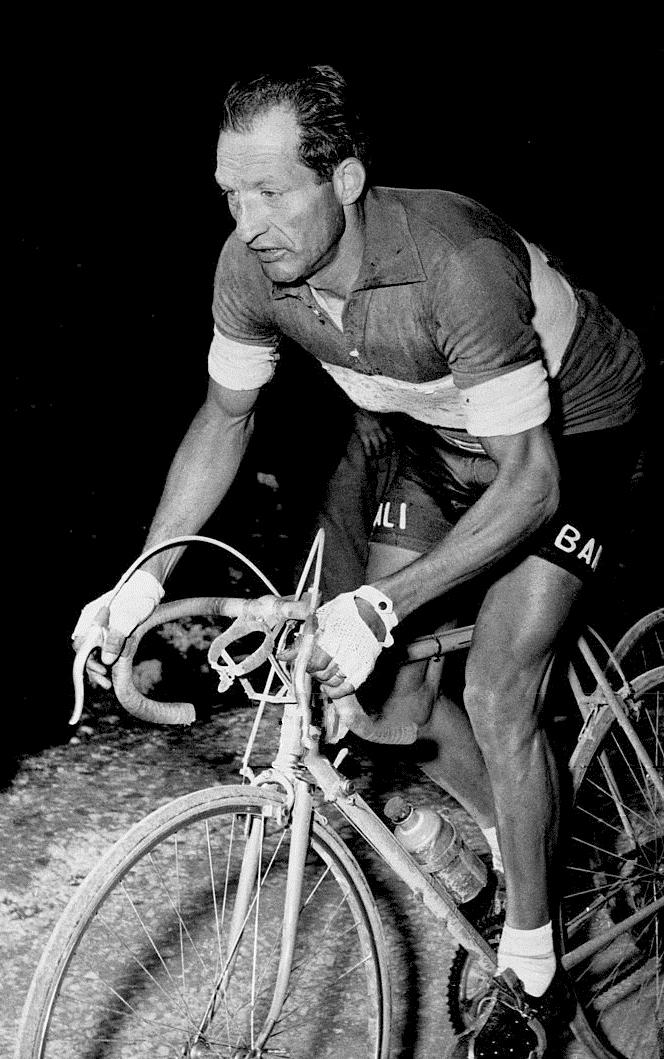

Eighty years ago, an Italian named Gino Bartali won the race. In all, the renowned cyclist won the Giro d'Italia three times (1936, 1937 and 1946) and the Tour de France twice (1938 and 1948). Those victories alone place him in the international pantheon of great cyclists.

But there’s another story about the Italian cyclist well worth knowing.

Bartali risked his own life during the Holocaust to rescue as many as 800 Italian Jews from the Nazis.

“He smuggled documents in the frame of his bike, thinking that if he would be stopped by the Nazis, he would tell them that nobody should touch his bike because it was set up perfectly for racing, it shouldn't be tinkered with,” says Jonathan Freedman, an avid cyclist who has researched Gino Bartali’s story.

“So, he was able to use his training to move around the country in ways that others couldn't because movement was generally restricted and under suspicion.”

World War II historians have only recently documented how Bartali smuggled documents, photos and messages past the fascist police to the Italian resistance while wearing the Italian racing jersey and pretending to train. It’s also emerged that Bartali hid a Jewish family in the cellar of his house in order to save their lives. Another story suggests that, in 1943, Bartali helped some Jewish refugees flee to the Swiss Alps by hiding them inside a small wagon with a secret compartment that he pulled with his bicycle under the guise of training.

Bartali was recognized in 2013 by Yad Vashem with the honorific "righteous among the nations" for his courageous efforts to save Jews during the Holocaust.

Freedman says he came across the extraordinary story of Bartali by chance. During one of his visits to Italy, his barber introduced him to the producer of a 2014 documentary film about Bartali called "My Italian Secret: The Forgotten Heroes."

The story of Bartali's efforts to support the resistance clearly inspired Freedman. "My grandparents were Holocaust survivors from Hungary, so when I first heard this story by chance … the story just really, really hit me. … it’s the romance of cycling, it’s the heroism, it’s the fact that he was a famous sports figure, and I thought, 'Wow, what an amazing story!'"

The chance discovery motivated Freedman to participate in a charity ride in Italy in Bartali’s honor. Freedman also encouraged members of the Israel Cycling Academy, Israel’s first professional cycling team, to retrace one of Bartali’s training routes from Florence to Assisi. It’s a challenging 120-mile stretch of road where Bartali once prepared for the intense Giro d’Italia competition. The route still stands as an amazing landmark and testament, says Freedman, “to Bartali’s heroism set against the backdrop of the war.”