Stivinson Mena lost his left leg, one finger and suffered genital injuries when he stepped on a land mine in Colombia, in 2015.

Stivinson Mena remembers the land mine explosion that lofted him so high, it left him hanging from a tree branch.

It was June 21, 2015, and Mena, a soldier, was 24 years old. He was patrolling a rural area close to the community of San Vicente del Caguán, Colombia.

Despite the magnitude of the blast, Mena was still conscious. Like other victims of antipersonnel mines, the first thing he did was look at his body.

Mena saw that his left leg was gone. He also had blood all over, along with wounds on his chest and hands. He had lost at least one finger and he had a buzz inside his head that has not left him to this day.

But something else was missing.

“When I looked at my penis I saw a broken testicle. … It was hanging because the explosive wave removed my camouflage,” he said to BBC. “That was the moment of pain I suffered the most.”

“I thought several things: ‘Now I won’t have a woman, I won’t be able to have kids,’” he added.

His fears were no exaggeration. The young soldier did not only lose his right testicle. He also had a partial loss of his left testicle and he suffered severe mutilation of the penis. These wounds are some of the multiple forms of genitourinary trauma, known as GU trauma.

“When I looked at my penis I saw a broken testicle … I thought several things: ‘Now I won’t have a woman, I won’t be able to have kids,’” he says.

During my research for this story, I noticed a great difficulty in speaking about this issue in Colombia, and even finding figures. But this is a wound that occurs in most wars in which troops are walking over ground that has any type of improvised explosive device or IED, such as antipersonnel mines or homemade bombs.

An antipersonnel mine: $2 and five minutes

IEDs are a popular war tool in armed conflicts because they are cheap and do not require a great investment of time or human resources.

“If the mine doesn’t kill you, the infection can,” is a phrase I heard several times from specialists and wounded soldiers.

Antipersonnel mines have left more than 11,400 victims in Colombia in the last 17 years, according to a recent report by the country's National Center for Historical Memory. Sixty percent of them were armed service members, while 40 percent were civilians.

Colombian records of combat wounds list around 15,000 names of soldiers, police officers, and members of the navy — most are amputees. The oldest victim in the registry turned 76 in February.

In the context of the new peace deal between Colombia's government and the FARC guerrilla group, cases like Mena stand out. The numbers suggest things have been looking up: There was a 70 percent decline in wounded soldiers from 2015 to 2016, and no new reported cases this year, according to Colombian army figures. The government and rebels have begun a joint process of clearing the land mines. But Mena was one of the last soldiers who were systematically mutilated by the war.

Like many other wounded soldiers here in their 20s, Mena is from Colombia's poor countryside. He remained in school until fifth grade.

A long path

Since “the accident,” as he calls it, Mena followed a similar route to many other Colombian amputee soldiers.

Badly injured, he was rescued by troops in his unit and rushed to the closest health center — the San Vicente del Caguán Battalion — where he was operated on and stabilized.

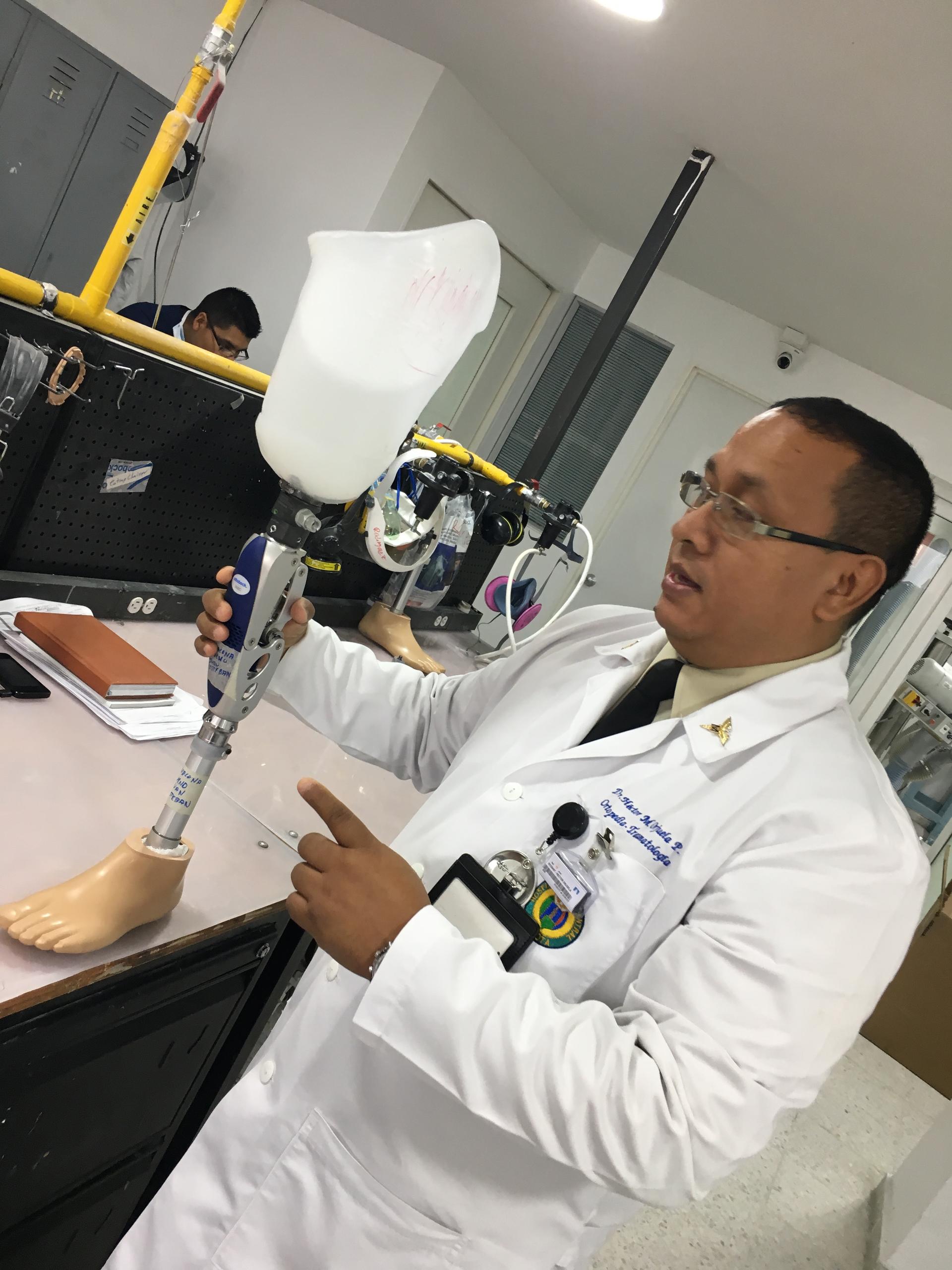

The next day, he was flown to a military hospital in Bogotá. His rehabilitation began with psychological support and a prosthetic leg, and it has continued for two years.

After a month in the military hospital, he was moved to the Health Battalion, a special rehabilitation center for wounded soldiers. Founded in the late 1980s, the clinic oftens hosts around 600 soldiers for long periods of time, and up to 1,000 people during the peak violence of Colombia's conflict.

Mena lived there for a year and nine months. He spent the time studying and working to regain the function of his genitals.

How many soldiers have genital wounds?

“Since they were wounds from high-velocity projectiles along with nonconventional weapons, they were traumas that compromised multiple organ systems: the extremities, the abdominal cavity, the external genitals. They were very complex traumas,” a reconstructive urologist who has worked in the field for more than 15 years told BBC World's César Cruz.

“Approximately 20 percent of the trauma victims had some form of distortion in the urinary or genital apparatus,” he says. That means, about 3,000 of the 15,000 victims suffered a kind of GU trauma.

“In the whole spectrum of wounds one could see a laceration of the penile skin or the scrotum, and even patients with avulsion [tearing] or extensive damage of the tissue that required penectomy. Or patients with avulsion of one or two testicles,” Cruz explained.

“What is a penectomy?” I ask.

“An extirpation of the penis,” he responds, meaning, to remove the organ. “But generally, what we did was partial penectomies, not the entirety of the penis.”

“Stivinson arrived with an amputated right leg because of a strong infection. That was what put his life at risk," Cruz says. "In urology, what we did were some maneuvers, damage control, and once we passed the critical phase of trauma, we knew we would have to face the reconstruction phase.”

The science of reconstructing a penis

Although Mena lost a large part of his external genitals and more than 50 percent of his testicles, the doctors assure him that they can recover 85 percent of his sexual function. They believe he will be able to urinate and even be a father.

On March 11, Mena was operated on by a team of 12 people in a six-hour surgery in which 105 specialists from various countries were present, and which was seen on live broadcast by more than 700 doctors from around the world.

“Stivinson has an absence of the penile urethra and part of the bulbar urethra. It is a segment of approximately 15 centimeters in length," said the urethral reconstruction specialist.

Doctors took tissue from inside Mena's mouth, oral mucosa from behind both cheeks, and inserted it on the underside of his penis, where part of the urethra was missing, Cruz said.

“These tissues are extended like a rug. The idea is that in six months, this rug can be dissected and we can make a tube from the part where his healthy urethra ends towards the distal part of the penis where there is another urethral segment,” he says.

Becoming a father

“When one loses a testicle, what they can do is place a silicone prosthesis that improves the esthetics,” Cruz explained.

“In our country, which is a country in which we have to limit our spending on the health system, we only place a prosthesis for the patient if the absence or alteration of their phenotype affects them psychologically,” the doctor clarified.

In other words, not all the soldiers who lose a testical receive a replacement. It partly depends on how the wound affects their perception of masculinity.

“With regards to fertility, I can tell you that many of our soldiers are incapable of reaching an ejaculation, so many require assisted fertilization techniques in order to be biological fathers,” he added. “We would have to obtain the semen, either through urine samples or from a part of the ejaculation that goes to the bladder. Or going directly to the testicle and taking a biopsy to extract spermatozoa.”

In Colombia, the army’s health system covers the entire cost of fertilization treatments for wounded soldiers. Nonetheless, there are no exact figures for how many service members have undergone such treatments.

Amputee sex taboo

Colombia is largely a male-dominated society, rooted firmly in Catholicism and traditional family values. Any sort of physical disfigurement, the loss of any limb, can pose challenges to a soldier's masculinity.

“After falling on a mine or having any irreversible injury, their self-esteem drops, their perception of sexuality changes, and there is a lot of fear,” says Diana Fajardo, a neuropsychologist from the Center for Inclusive Rehabilitation, which is the last stop toward soldiers' recovery.

“The soldier becomes more irritable, more insecure, and with many fears to face with regards to sexuality — even with their therapists — and those who really help with the issue of sexuality are the peer,” she says.

Who might a peer be?

"The peer is that person who is in your same situation and, for good or bad, has a more advanced treatment than you. It’s who guides you and helps you, because in Colombia the issue of sexuality is still a little complicated. There is a lot of taboo with this topic," she says.

The peer is fundamental in the process of rehabilitation, and aids with the transition into civil life.

Florián and Pedraza

One of those peers is First Sergeant Francisco Pedraza and professional soldier Juan José Florián, with whom I had the opportunity to talk about sex, after a dozen wounded soldiers declined.

Pedraza is probably one of the most charismatic wounded officials I have met. Amputee soldiers admire him and seek his advice on just about anything. He eases their doubts about the future, and helps them resolve issues like using the restroom or how to make love when you lose your legs.

“During the months I was in the hospital I never had an erection. Since I had shrapnel in the kidney, they told me it was normal, but it’s no secret that for the ego, the macho, an erection is something essential,” Pedraza said.

“First thing that comes to your mind is that my virility is lost. I thought, ‘No woman will ever want to be with me.’ And I already have my kids; it must be different for those who have never had kids,” he says.

Florián, the soldier, has a more severe disability.

“Don’t ask me what did I lose, but rather what is left,” he jokes when asked about it.

He lost half of both arms above the elbow, his entire right leg and an eye. Resilience is the best word that defines him.

He is a committed athlete. He has been training for two cycling world cups in Europe in June. He also studies psychology at the Sergio Arboleda University in Bogotá. He drives his car, answers his phone, and manages to hold a hot coffee mug and drink it without any issues. Above all, he keeps his mood up.

Several soldiers spoke of him as an exemplary peer. “If this guy ended up like this and could overcome, then I can too,” at least three different men said.

“You are really never prepared for this,” Florián said.

“The army prepares you to kill another man but not how to live without arms or legs. … After the accident, sex was not important for me, everything was focused on what I would do for the rest of my life.

“Although my wife demanding intimacy, I avoided her the whole time. I told her that my stumps hurt, that I had nightmares; I told her I hallucinated. I did not have the strength and I feared telling her what was happening to me,” Florian said.

“Besides, the treatment in my case was focused on me. They never asked my wife what she thought of sleeping with a man with no arms or legs. … If it was tough for me, imagine what it was for her, if she had been with me when I had everything, then she would have to sleep with half of a body,” he lamented.

Both Florián and Pedraza split from the partners they had during their debilitating incidents. But both men say they are satisfied with their sex lives, which they were able to rebuild with time. However, they say, for others it’s not as easy.

Sex workers, Colombia's sex therapists

“Soldiers represent manhood, they are desired by women. To face a life after the accident, completely destroyed, it is complicated. And here there are no references, but I have read that in other countries there are sexual therapists that are legal,” Florián explained.

And that is how we arrived at the issue of prostitutes for many amputated or paralyzed soldiers, who have irreversible genital injuries.

“They are young men who are 26, 27, 28 years old. They have a lot of fear about tackling the issue” of sex, said Fajardo, the psychologist. In Colombia, “there are places here for sexual workers, or prostitutes.”

“You hear from the soldiers that it's their partner who takes them to these places,” she added.

“In those places, the women know how to stimulate them, what places to caress, how to touch or stimulate them so their sexual parts are satisfied,” Fajardo said.

The future for Stivinson Mena

The report from Cruz regarding the reconstruction of Mena’s penis is encouraging. He says it has much to do with his optimistic mood. Mena has another upcoming surgery, and will need medical supervision for the rest of his life. But in a year, doctors say, he will be recovered.

And Mena has a lot of plans. I visited him in late April at the Center for Inclusive Rehabilitation, where he has resided since February. He said that while he waits for his next surgery, he is finishing high school. He will move with his girlfriend, Angie Paola, to his hometown, in the Pacific region of Colombia.

“I want to go back to Quibdó to start my own business, a grocery store with a butcher shop,” he said.

When asked about the kids he wants to have, he said he already came up with a name for the first one: Camilo.

“And what about if she’s a girl?” I asked.

He laughed. “Well I’ve actually never thought of a girl.”

A version of this story originally appeared in Spanish on bbcmundo.com and is part of the documentary The Silent Wound, by BBC World Service Radio.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!