How a massacre of a village’s Jews by their neighbors in WWII Poland is remembered — and misremembered

Jedwabne, Poland

How do you choose what to remember, and what to forget? Maybe you don’t choose, consciously — at least, not always. We all have moments we’d like to forget — bad decisions, moments in life, or chapters in life, we wish we could just erase or, at least, make sure no one thinks less of you because it happened.

What happens when a whole society tries to bury a memory? Plenty have tried. Americans have, at different times in history, papered over massacres of Native Americans, treatment of slaves, the Civil War itself. Ask a Northerner and a Southerner what that was all about, and even today, they’re likely to give different answers. Some of the current red state/blue state, left/alt right divisions can arguably be traced back to the very different stories different groups have told themselves about what America is and should be, and what role they’ve played in trying to achieve the kind of America they want.

To an important degree, we are the stories we tell ourselves. And how collective memories are formed not only shapes an understanding of the past, but also a path into the future.

Memories of atrocities are especially tricky. If you were a victim, you might try to forget, or make sure everyone remembers — like Holocaust survivors, who hope that remembering that past ensures it won’t be repeated.

Perpetrators, on the other hand, would often just as soon bury the past. Nothing to see here, nothing to remember — move on. Or, the memory gets changed from something shameful into something less toxic.

In the Polish village of Jedwabne, where neighbors filled a barn with hundreds of Jewish women and children in July 1941 and then set it on fire (after killing many Jewish men and boys and putting their bodies in the same barn), the story villagers long told was that the massacre happened, but the Nazis did it.

And that worked, for awhile. A monument to the dead on the outskirts of the village bore an inscription that blamed the Germans for Jedwabne’s Jewish dead. And then, in the year 2000, Polish-born American historian Jan Gross refuted that story in his book Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland. In his research, he dug into the history of the incident and found strong evidence that Germans hadn’t killed the Jews of Jedwabne; their neighbors had.

This wasn’t the story the villagers of Jedwabne had told themselves about what their relatives and neighbors did. And not everyone there was ready or willing to absorb this new story. So when Polish President Aleksander Kwaśniewski came to Jedwabne with lots of international journalists on July 10, 2001, the 60th anniversary of the massacre, to install a new monument and apologize to the Jewish people, many of Jedwabne’s residents stayed home.

Nina Porzucki, cohost of The World in Words podcast, went to Jedwabne to talk to villagers about this atrocity, and about how the history of it has been told over time. Her experience there, augmented by interviews with Jan Gross, is the focus of this Whose Century Is It episode.

Why focus on an atrocity that happened 75 years, in a podcast that looks forward into the 21st century? Because the past is present. The past shapes an important part of who we are. And the past can provide a warning to those who choose to heed it.

Germany has been active in facing its past, trying to be vigilant against its darker impulses. And even there, the Alternative for Germany nationalist party has gained ground. In Poland, as elsewhere around Europe, full-throated opposition to immigrants and refugees has become more common. In 2015, Poles elected the right-wing, nationalist Law & Justice Party, with its platform of “Poland First.” Its leader, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, talked about refugees spreading disease — eerily like how European anti-Semites talked about Jews before the Holocaust.

Hate speech can lead to more hate speech, making normal the ‘otherizing’ of human beings. From there, violence against those ‘others’ is easier. Just think of what happened in Rwanda in 1994. Hutus had been told for years that their Tutsi neighbors were "cockroaches," and that they needed to "clear the brush." That ended up meaning hacking 800,000 of their Tutsi neighbors to death with machetes in just three months.

Atrocities like this, and the Holocaust, and smaller-scale incidents like the massacre in Jedwabne, and the shooting of an Indian tech working having an after-work drink with a friend in Kansas, have the power to shock, because they are rare. People don’t normally do this to each other.

But many people, perhaps most of us, have it in us to act in ways we couldn’t imagine possible in normal times. Many people, if they believe their lives or interests are threatened, will lash out. Many people, if given a green light, will express baser feelings that, at other times, they know to keep to themselves. Take as an example Iowa Rep. Steve King, tweeting, “We can’t restore our civilization with somebody else’s babies.”

The pushback he got from other Republicans might have shut him up for now, but with Donald Trump as president, and Steve Bannon as one of his key advisers, King seems to have thought he saw a green light flashing.

And so we’re left to face our demons, in America, in Europe, in the white developed West, as the rest of the world catches up and increasingly expects the comforts, rights and dignity we’ve enjoyed for a couple of centuries. If we were them, we’d expect the same thing. If they were us, perhaps they’d act the same way.

But what keeps peace, in the world, and between people, is tolerance and respect. American is a country built around that concept, even if it's lived imperfectly. Moving away from those basic principles is a slippery slope to dark deeds. Just ask the villagers of Jedwabne. Not that many of them would tell you.

*****

For more on this subject, check out Facing History & Ourselves, and this 2011 story by Mary Kay Magistad on how Rwanda has been doing in facing its own past.

For more of Nina Porzucki's stories from Poland, listen to:

Unearthing photos and memories of life in the Lodz ghetto

In Communist Poland, the punk thing to do was to sing in English

Fighting for press freedom with the Polish national anthem

Poland's right-wing government thinks this WWII museum isn't 'glorious' enough

Policing the language of the Holocaust in Poland

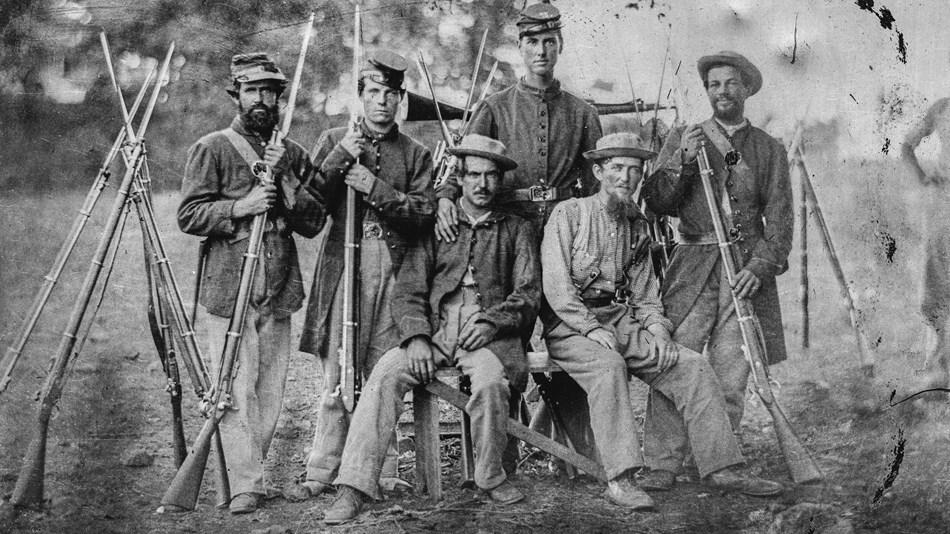

Correction: A previous version of this story contained a photo that was incorrectly identified as depicting the Jedwabne barn burning, where an estimated 340 Jews were killed. It actually depicted the burning, at the end of World War II, of a building in Germany's Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Some 50,000 people, mostly Jews, died in that camp.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!