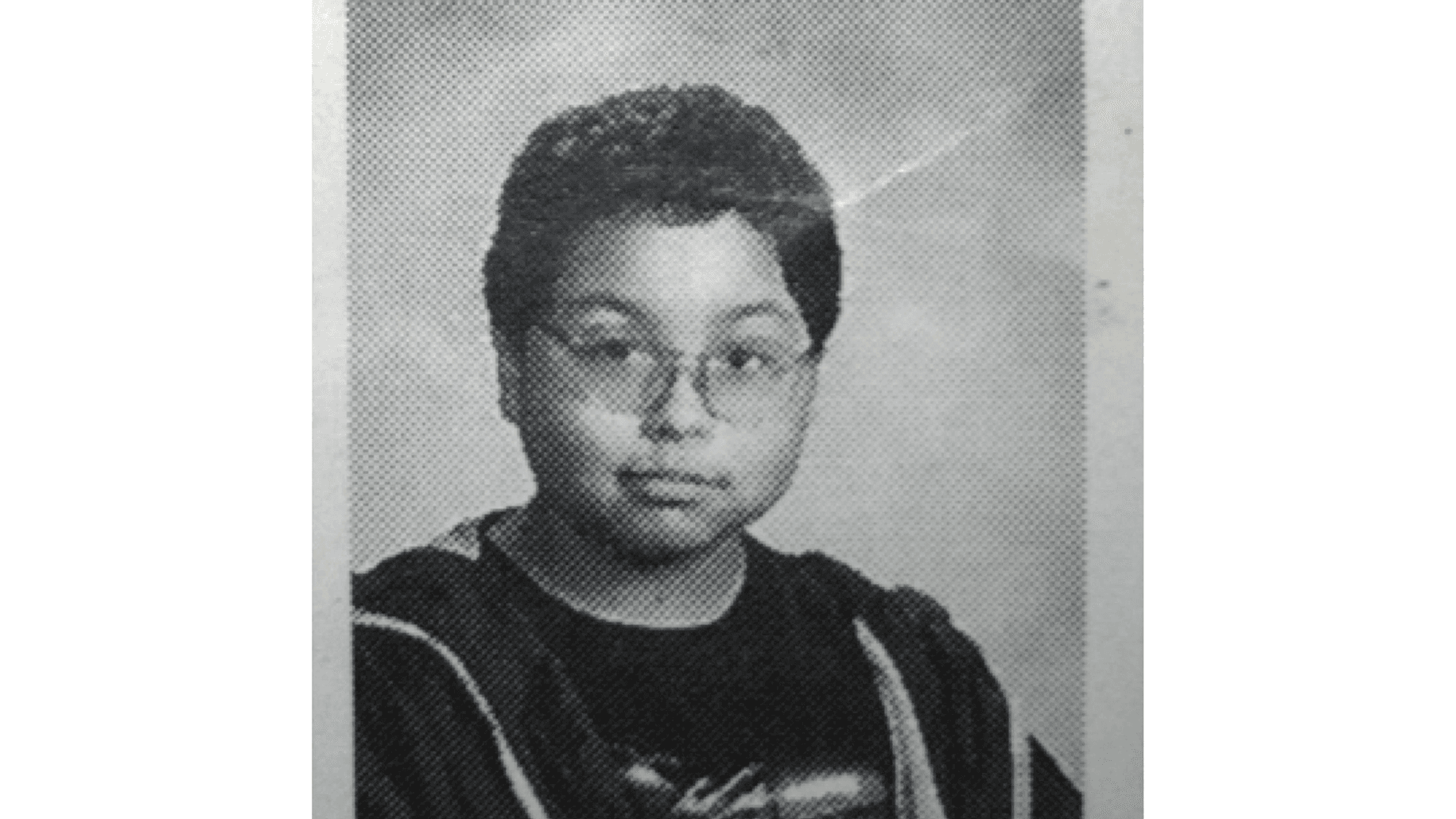

The author, Hendel Leiva, in second grade in Brentwood, New York, in the mid 90s. That year, he learned that using hateful words can have big consequences.

After the presidential election, posts on Twitter by Gizmodo reporter Rae Paoletta caught my attention. Through her tweets, she was actively documenting hateful acts happening across the country, many committed in Donald Trump's name.

Not long after, the Southern Poverty Law Center released its report of almost 900 acts of hate that occurred in the 10 days after Trump's victory. People reported incidents from nearly every state in the US. And these kinds of acts continued. In Long Island, where I live, I read reports about swastikas being spray-painted on sidewalks in mid December.

Interactive: How likely are you to be the victim of a hate crime?

I want to be proactive — in the most uncomfortable way I can imagine. I want to share a painful story I've lived with for more than 20 years, the moment I too made the mistake of making a racist remark to a classmate. And how it became a pivotal moment in my life.

I was a second grade student at Laurel Park Elementary in Brentwood, New York.

The incident began with a small argument I had with a classmate — I want to respect her privacy so I'm going to call her Brianna, which is not her real name. My immigrant parents taught me not to draw negative attention to myself so their advice didn't really help me understand how to resolve conflicts. I would avoid fights at all costs to avoid detention or suspension — which in my parent's eyes would be the worst kind of trouble possible.

I tried to ignore Brianna, but that made her angrier. She started speaking to me sarcastically. My anger bubbled: I wanted to hurt her, like she was hurting me.

And that's when I said the words that changed our lives: “Well, I don't like black people anyway.”

Brianna's face fell. She walked over to the teacher and whispered in her ear.

With an upset expression on her face, the teacher called the front office and an administrator walked me out of class. I was taken to the principal's office, where my mom was sitting with tears streaming down her face. I sat next to her silently; I didn't know how to explain what I had said in Spanish. To tell my mom the reason she had been called to the school in our native language, to tell her I had said something racist to a classmate would be a moment of great shame.

The principal and vice principal interrogated me in front of my mom. I didn't have an explanation. I wasn't racist. I had heard my mostly Hispanic friends make jokes about our black classmates before, always behind their backs. However, at that moment in the principal's office I realized the cowardice of my Hispanic friends: Saying racist words was something extremely bad, and I was paying for it.

“What if we said to you that we didn't like you because of your glasses?” the principal asked. I stammered, feeling as if my identity was being attacked. I was already a self-conscious second grader; the pressure from my parents to be obedient, my developing weight problem, and most recently the large glasses that sat on my face, all added to the struggles I was experiencing with my identity.

“I guess … I wouldn't think it was right.”

I walked out of the meeting without a suspension, but I did take with me the shame that came with putting down another person for her skin color. I vowed to never use race, or racist words to ever hurt someone again.

After the incident, I stayed away from Brianna. I thought about directly apologizing to her, but I was afraid I would end up in the principal's office again. In fifth grade, she invited me to her graduation party, to my surprise. I went, feeling grateful we were putting the ugly incident behind us.

In seventh grade however, she denounced me as a racist in front of our classmates on the bus. I was shocked. The anger in her eyes stopped me from asking why she had chosen that moment to humiliate me. A part of me understood. I had committed an unspeakable act in second grade; I deserved the punishment.

The next time we crossed paths was as seniors in the same AP Biology class. In that class, I kept my distance and tried to be friendly. I wanted to avoid any conflict.

One day, though, I heard her talking to a mutual acquaintance: “Why are you even friends with him? He's a racist. He has something against black people.”

I froze, and my heart sank. I had no words. The incident that had happened 10 years ago was still part of both our lives.

I went home that day, defeated and humiliated. I wanted to face the issue head on and I wanted to give her the opportunity to express the rage she held towards me. It was only fair. I took a piece of looseleaf paper and wrote everything on my mind. I wrote furiously — and when I was done, I had written five pages of a long-overdue, heart-wrenching apology.

I remember writing in the conclusion: “I apologize to you, your family, and the African American community. And if you still don't believe me, please — crumple these papers, and throw them at me as hard as you can.”

The next day I walked up to Brianna, my heart beating out of my chest. I handed her the letter. She opened it, and began reading. Finally, she looked up. I noticed her eyes had softened: there was no anger, just sadness.

“Thank you for this,” she said. “I'm sorry too.” I told her that her anger was understandable and justified, and that I was humbled to have been given the opportunity to make things right between us.

At the end of the year we signed each other's yearbooks, expressing a mutual respect and admiration for each other. It was the most gratifying moment of my high school years.

I saw Brianna a couple of years ago, nearly 10 years after we had graduated. We hugged like old friends. It was almost like starting over as the friends we should have always been.

The lessons I learned from the experience — and also the shame — never quite go away. When I think of Brianna, I think of a strong, accomplished, beautiful, unapologetic black woman. I also think of being the first person who put her down because of her race.

As I watch dozens of new hate-based incidents emerge on social media every week, I fear the normalization of hate that devolves from hateful words into heinous actions. In the past few months, videos have emerged on social media of people in shopping malls being malicious towards immigrants, Muslims, blacks, and just last month, those words even led to the death of Srinivas Kuchibhotla in Kansas.

President Trump is playing a dangerous game. During his candidacy, when asked about his rally taking place 1,000 feet from the site where Marcelo Lucero was murdered in the Village Of Patchogue, he said he had “never heard of it,” and he never condemned it. His denouncement of hate at the beginning of his joint address to Congress lasted seconds, which I saw as dishonorable to the very real victims of hate crimes.

This is why I need to step forward and take ownership of my own contribution to the climate of hate, even if I was a second grader, because our president lacks the courage. There is no excuse.

Hendel Leiva is an immigration reform advocate and immigrant integration specialist from Brentwood, New York. He works for Race Forward, an organization that researches, publishes on and advocates for racial justice.