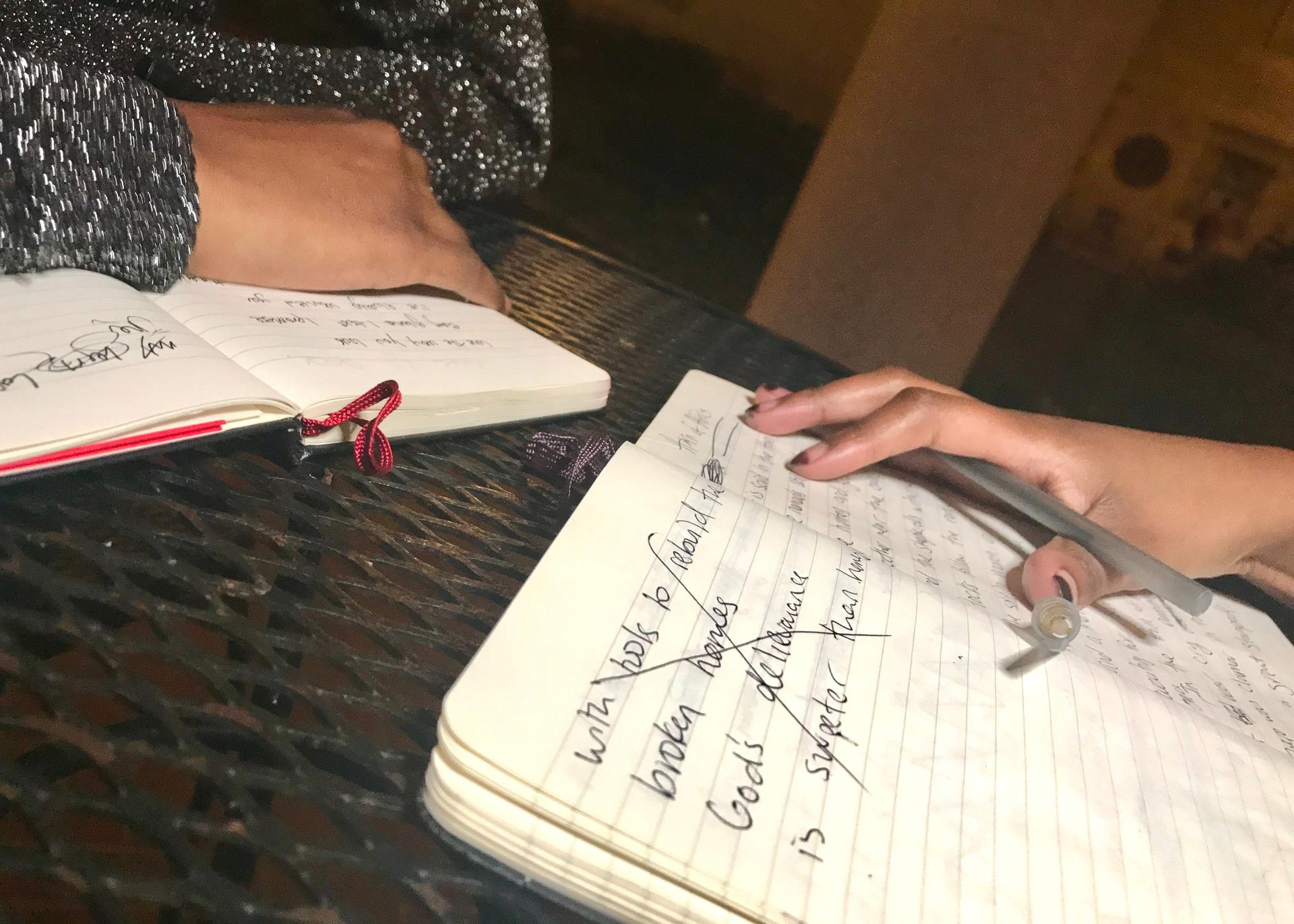

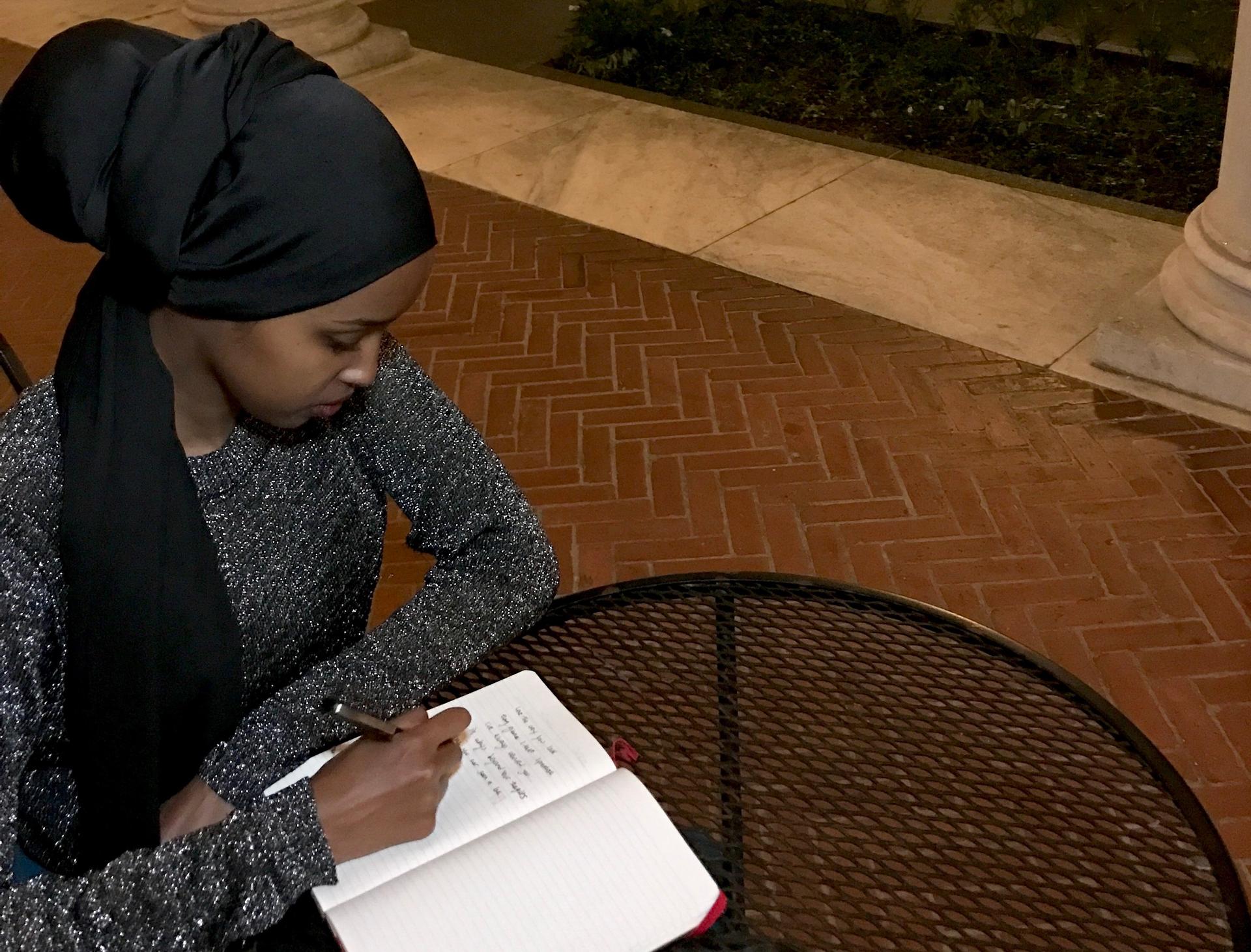

Amal Hussein and Hamdi Mohamed work on poems together.

Amal Hussein and Hamdi Mohamed have a lot in common. Both were born in Kenya, where their parents had fled as refugees from Somalia’s civil war, and both came to Boston when they were just a few years old. They’re both in their early 20s now, they’re both poets — and both of their grandmothers are poets.

But there’s one crucial difference in the two women's stories.

Hamdi grew up with her ayeeyo — her grandmother — in the house, whispering poems in her ears. Amal has only known her ayeeyo on the phone. They haven’t seen each other since Amal was a small child.

“She lived through when Somalia was really beautiful and peaceful, and she lived through the civil war,” Amal recalls. “And when we left, she didn't want to come. She was always like, 'this is my sand, this is where I feel like is home.'”

As a young girl, Amal would spend hours talking on the phone with her grandmother and watching videos of her performing at weddings back in Somalia. Families would often call on her grandmother to recite a style of poetry called gabay — which as you can hear in this video is as melodic as it is lyrical.

But even though Amal grew up hearing poetry in the house and on the phone, she never dared write her own until she met Hamdi.

The two girls went to the same Islamic middle school in Mansfield, Massachusetts — way out in the suburbs, south of Boston — and they shared the same grueling commute, beginning each day before sunrise.

“I guess destiny was forced,” Amal says. “We just had to get to know each other.”

It started on the commuter train, on their way home from school. Usually, Hamdi was the quieter one, while Amal was quick to make friends and take the lead on the basketball court. But when it came to poetry, Hamdi was the instigator.

“And she was just writing, writing,” Amal says. “I would go and bother her and see what she was writing. And she was like, 'OK, now it's your turn. You have to write a poem.'”

Hamdi recalls, “I did kind of force her to write it too. Cause she was always forcing me to do things that were out of my comfort zone.”

From there, Amal says, “We just got into this habit, where whenever we're on the train, we're writing poetry.” They would pass the same paper back and forth, letting that cycle flow on and on — just like the gabay of their grandmothers.

As young girls, Hamdi and Amal wrote all their poems in English, the language they knew best. Then a few years ago, Amal decided she would write a poem in Somali, and she wrote it with one person in mind: her ayeeyo.

The poem was only seven lines long, but it was harder to write than you might think.

The first challenge, Amal says, was just the language. “You know how there's like regular English, and then there's poetic English like William Shakespeare. It's like that,” she explains.

Then using this poetic language, she had to fit the words into specific rhythms — like one of Shakespeare's sonnets — and use rhymes and alliteration in all the right places. And the message couldn’t be too direct. She had to tuck it into metaphors and proverbs — references to sand, acacia trees and other imagery from the Somali landscape.

Finally, after checking those seven lines of poetry with her parents, relatives, and anyone who would listen, she called her grandmother and recited the poem over the phone.

At first, her grandmother said nothing, Amal recalls. “She was just silent and started crying. And then she was like, ‘You're definitely my granddaughter. You took after me when it came to gabay, and I want you to hold onto it, and I want you to continue, and I don't want anyone to ever tell you that you can't do it.'”

Amal’s grandmother told her that it doesn’t matter whether she writes in Somali, English, or any language — no matter what, “we have that connection, that gabay connection.”

Hamdi, meanwhile, is still working on her first Somali poem, but she already knows what it will be about. It’s called “For my Ayeeyo” — for my grandmother.

“For My Ayeeyo” by Hamdi Mohamed

Worn brown hands claps black prayer beads

A golden chest, a haven for dust

And memories

You whisper behind a veil

Wrapping proverbs like gifts

t is the festival of ‘Eid

I sat between your brown thighs

You twisted my thick hair

Into rows

To remind you of home, you say

You miss weaving baskets

For the harvest

The way the rain smelled like perfume

And clung to the skin like fresh honey

You say Hamdi, our skin and bones

Always know where they came from

Don’t forget you kin

Your eyes are pearls

Molten silver

Even the cataracts

Can’t subtract from you

At the airport

My hands crushed yours

I was the spoiled child

In every supermarket

Crying for something I couldn’t have

Still you didn’t scold me and

Shushed my mother

You were the strong oak tree

Under whose leaves I sought refuge in

It is winter now,

The leaves are almost gone

The rest are brown and worn

I wish they would stay

I feel heavy Ayeeyo

When we speak on the telephone

My memories of your hands are fading

Henna we used to wear black and red

Now gone

Make a prayer Ayeeyo,

With your black prayer beads,

God is closer to you than I

I am coming soon Ayeeyo

Listen for my skin and bones

They always know

Where they came from

You can hear the full story of Amal and Hamdi — as well as excerpts of their English and Somali poetry — on The New American Songbook, a podcast about music and immigration produced by The GroundTruth Project and WGBH News, with funding from Mass Humanities.