Kehinde Wiley reimagines old portraits because ‘if Black Lives Matter, they deserve to be in paintings’

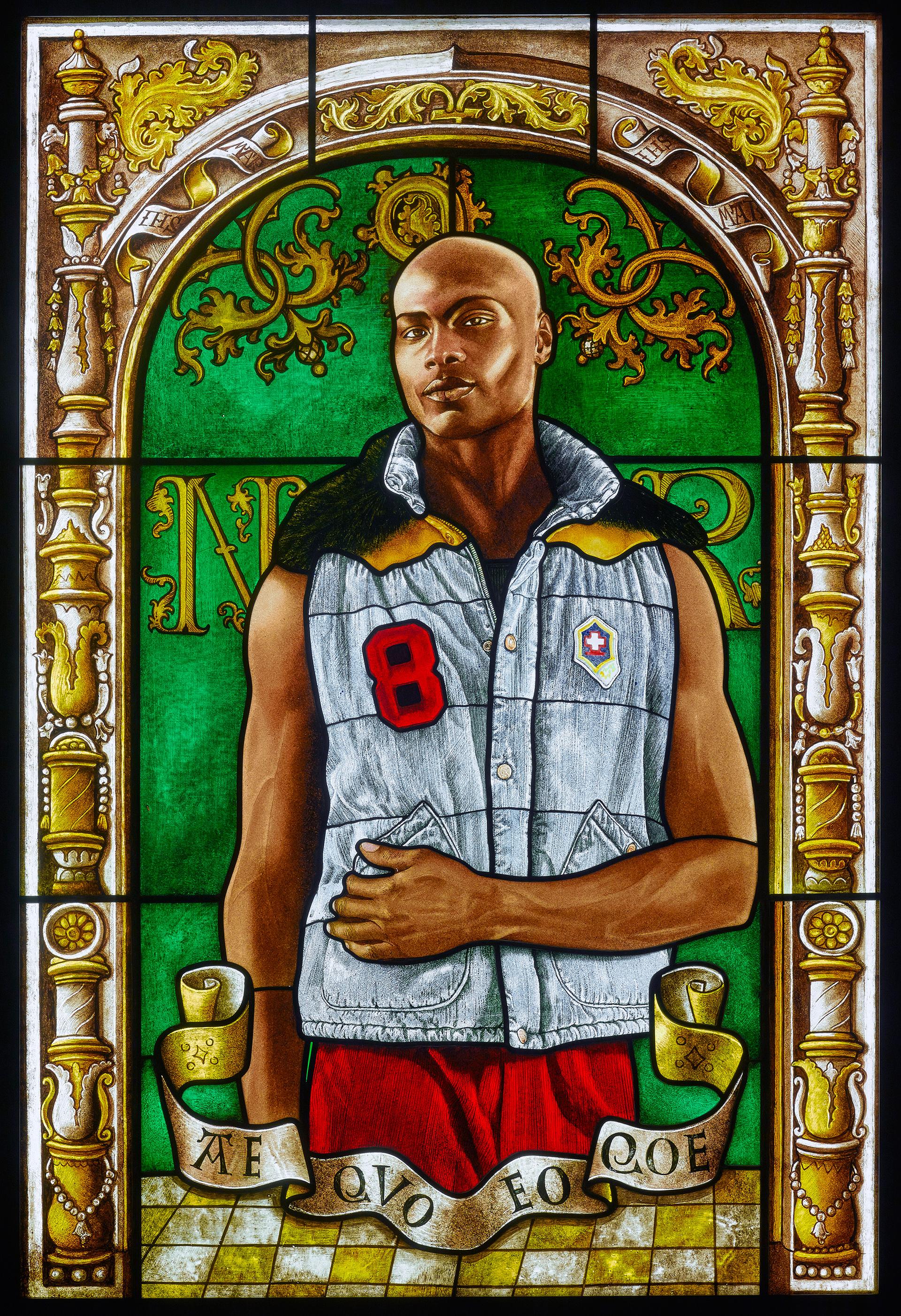

This image shows some detail from "Mary Comforter of the Afflicted," a stained-glass portrait by Kehinde Wiley.

New York-based visual artist Kehinde Wiley says he’s not very religious. You might think otherwise from looking at some of his work.

Wiley currently has a show at the Petit Palais in Paris called “Lamentation.” It features 10 monumental works in stained glass and oil on canvas. Each portrays a traditional religious scene, in the style used by European artists during the Renaissance. Wiley reimagines each scene, placing at its center a modern-day person of color, wearing shorts and tank tops and the like.

The results are both beautiful and surprising to the viewer. See for yourself. Below, on the left, is a stained-glass portrait from the 16th century called “Saint Ursula and the virgin martyrs,” by an unknown artist. And on the right is Wiley’s modern reinterpretation.

Wiley describes what he does as an “intervention.”

“By and large,” he says, “most of the work that we see in the great museums throughout the world are populated with people who don’t happen to look like me. As a child, I grew up studying and worshiping those great works of Western European painting. But I also wanted to fulfill the goal of feeling a certain personal presence in that work.”

In other words, Wiley wanted to see himself in those grand heroic portraits. And as an artist, he sees an opportunity to take those centuries-old depictions of glory, and use them to make a statement that’s very much about the present.

“At its best, what art does is, it points to who we as human beings and what we as human beings value. And if Black Lives Matter, they deserve to be in paintings.”

Wiley says the reaction at the opening of his show in Paris last month was profound.

“I’ve never had so many museum guards walk up to me like they did in Paris, where they said, ‘Oh my God, I’ve never seen this many black bodies in a public space,’” says Wiley.

He says the guards who came up to him were a cross section of French society: black, white and North African. And he attributes their reaction to the power of his big, stained-glass portraits.

“The resplendent light coming out of that stained glass is not about nationhood, it’s not about race. It’s about being powerful in the world, glowing literally,” he says. “And if art can be at the service of anything, it’s about letting us see a state of grace for those people who rarely get to be able to be seen that way.”

By the way, Wiley’s full body of work goes beyond religious iconography. It includes a series of projects he calls, “The World Stage.” Each project focuses on a different country around the globe, always with a black or brown body at the center of each portrait.

His current exhibit at the Petit Palais in Paris runs through January 2017. Wiley acknowledges that this is a delicate time for his work to be exhibited in France. Far-right politicians there have seen a surge in support because of concerns that too many refugees and immigrants are coming into the country.

“I think that it’s obviously something that we see here in America,” he says. “We see it in the Brexit. We also see it in France. And all of those black and brown bodies that are in places [like the recently dismantled migrant camp in Calais] called the Jungle … [those places] have to be remembered as places that were once places of refuge for Eastern Europeans, Jews and homosexuals.”

Wiley’s conclusion? “Europe has been a place of refuge. Why should it stop with black and brown bodies?”