US President Lyndon Johnson looks on as Secretary of State Dean Rusk signs the Treaty for the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons on July 1, 1968.

No matter how much the world has changed since the Cold War, as other threats like terrorism and global warming have come to dominate our fears, nuclear dangers are still with us.

But every day, there are ordinary people collaborating in extraordinary ways to keep the rest of us safe from them. For some, it's a family tradition.

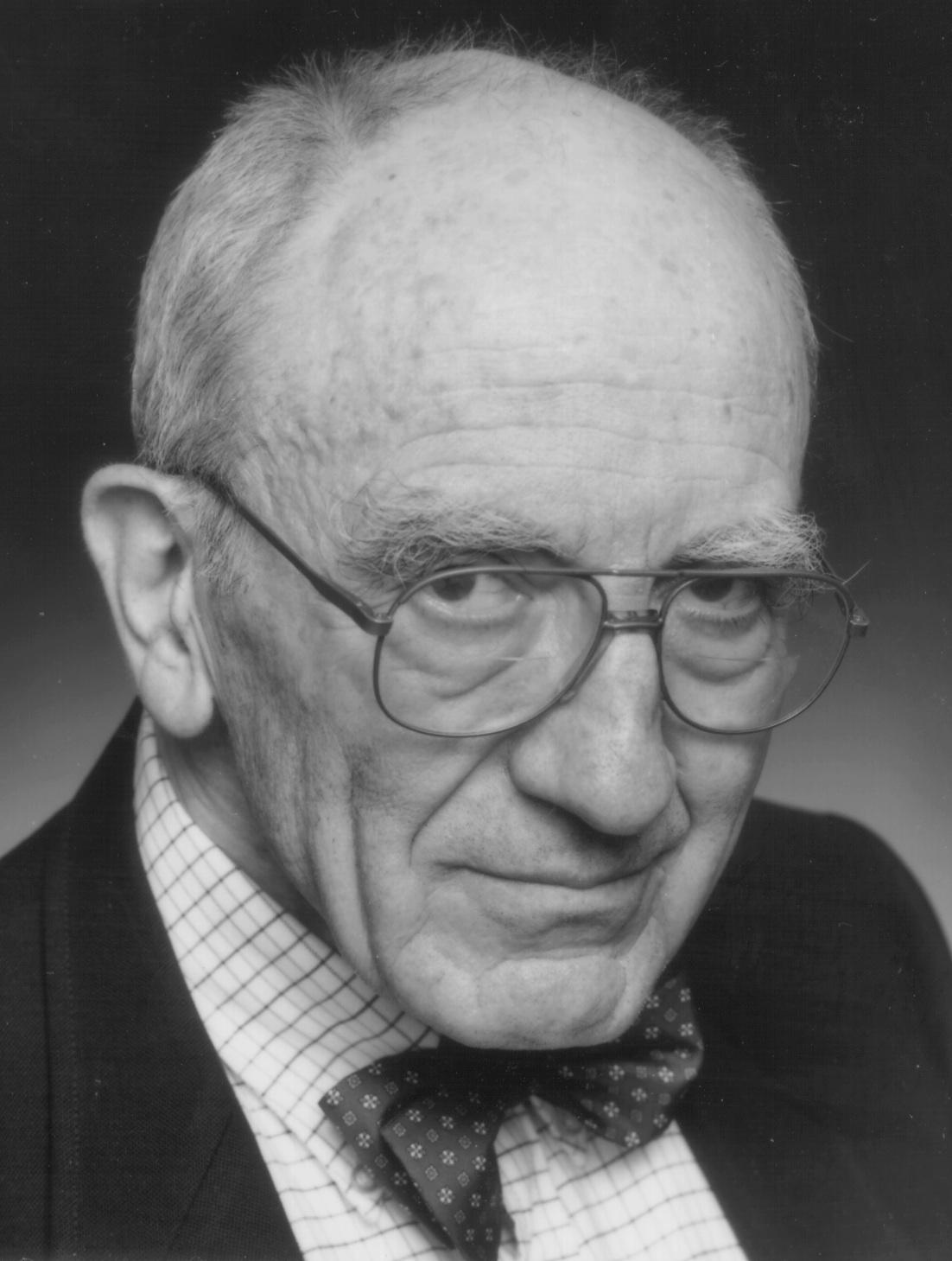

Matthew Bunn is a nuclear policy expert and professor at the Harvard Kennedy School, where he also serves as co-principal investigator for the Project on Managing the Atom. His father George Bunn, who died in 2013 at the age of 87, was also a leader in the effort to control the spread of nuclear weapons. A lawyer and diplomat, he helped create the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency under President John F. Kennedy and played a key role in drafting and negotiating the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty that was signed in 1968 and went into effect in 1970.

Matthew Bunn spoke with us about about his father, their careers, and the fight to keep the world safe from nuclear disaster. You can hear George Bunn recall the development and enactment of the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons here, and also find many of his papers at this memorial site.

On his father's first encounter with nuclear weapons

"He was in a ship bobbing around in the Pacific at the end of Word War II which was slated to be part of the invasion of Japan. He honestly believed his life was saved by dropping the bomb on Japan. He came back to Madison, Wisconsin, where he’d grown up and became a physics graduate student.

"And his father gave him a copy of the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, which laid out a concept for global international control of all aspects of nuclear technology to ensure disarmament. And he thought, 'Well, if we’re going to have disarmament, we’re going to need treaties. If we're going to have treaties, we’re going to need lawyers, so I'll go off to law school.' So he went off to law school specifically with the idea of controlling the bomb."

On the impact of Hiroshima

"Bernard Brodie, who later became one of the founders of the whole field of nuclear strategy, had been a naval strategist, and went to the drug store to buy the paper the day after Hiroshima, looked at the headline, turned to his wife and said, 'Everything I've ever written is obsolete.' Because one bomb from one plane could destroy an entire city.

"That was something dramatically different from anything that had come before. It was a new kind of threat to civilization. We had just as a world gone through a war that had killed tens of millions of people, and the notion that our species would now have bombs available to it where a single bomb could destroy an entire city was just terrifying."

On the differences between his work and his father's

"I ended up focusing on the intersection between the technology and the policy. … I've always focused on the technology of nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles and so on, and policies that are needed to manage the danger. My father on the other hand, as a lawyer, focused mainly on the treaties and the legal aspects and the international organizations and norms. Toward the end of his career, after the 9/11 attacks, actually even leading up to the 9/11 attacks, both of us had gotten involved in the question of security for nuclear weapons and the materials needed to make them, to keep them from falling into terrorist hands.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D6QBarfleQ-A

"Immediately after 9/11 there was a global international meeting at the International Atomic Energy Agency where my father and I both spoke on this topic of security for nuclear weapons and materials, and he said at that meeting, 'If I had known then what I know now about what terrorists could potentially do, I would have tried to make sure the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty included provisions to require that all these weapons and materials be secure."

On the Soviet Union falling apart in 1991

"The reality is that most of their security system fell apart with it. It was designed for a closed society, with closed borders, everyone closely watched by the KGB and nuclear workers who had the best of everything Soviet society had to offer. All of that went away. They literally had gaping holes in fences at nuclear facilities and highly enriched uranium stored in the equivalent of a high school gym locker and a padlock that could be snapped with a bolt cutter from any hardware store. There was one case where a thief who stole kilograms of highly enriched uranium didn't even bother with a bolt cutter. He took an iron rod and put it inside the padlock and twisted and broke the padlock and made the mistake of leaving the broken padlock lying in the snow, which otherwise nobody would have noticed for a long time that the theft had occurred.

"So I got involved in the early '90s working with Russia to make sure all this nuclear material was locked down and my father got involved as well.'"

On working with his father

"Both of my parents had a feeling that you can't waste your life on this planet. You have to try to make yourself happy, but try to make the rest of the world a better place than it would have been if you'd never been here. I think that basic attitude toward life was absorbed by the children."

" … Remarkably in the entire course of our careers [my father and I] only wrote one joint paper together. One of the hilarious incidents was I was at that time the editor of the leading journal in the field, Arms Control Today, and my father and a colleague of ours had written an article about who ends up with the legal rights under different treaties for the Soviet Union of all these new states arising out of the collapse of the Soviet Union. And there was a sentence in that article, I read it five times, I could not understand what the heck it was trying to say. I called up my dad and said, 'What the heck are you trying to say here?' And he said, 'Well we couldn't agree on that one so we intentionally wrote it so you couldn't understand what it said.' I said, "I'm sorry, I am not putting in a sentence that even the author doesn't know what it means. You guys figure out what you want to say or I'm taking it out!"

On how nuclear threats have evolved

"Until very recently most Americans had forgotten about nuclear dangers. Many people thought the nuclear danger went away when the Cold War went away. And that's not true. And the next president is going to face some very serious nuclear dangers.

"We have thousands of nuclear weapons in the nuclear world today, thousands in fact ready for immediate launch.

"We have a very unpredictable dictator in North Korea that now has close to a couple of dozen nuclear weapons, is producing more, testing more, testing longer-range ballistic missiles.

"We have a nuclear deal with Iran but some of the key provisions only last for a short period of time, so the next president is going to have to figure out how to use the time we bought with that deal.

"We have an unbelievable crisis with Russia where there's a real war scare going on today in Moscow. They've just mobilized 40 million people across the [country] in a civil defense drill and there's talk on the news about the coming war with the United States.

"There are very real dangers of inadvertent conflict, whether it be in the Baltics or elsewhere in Europe. We're getting into some serious tensions with China and we still have the issue of terrorists. Yes, we've taken out Osama bin Laden. But now we have the Islamic State. And we don't have a lot of evidence that they have the kind of focused nuclear weapons effort that al-Qaeda did have, but there are some hints. If they ever turn to nuclear weapons, they've got more money, more people, more territory under control, more ability to recruit experts globally than al-Qaeda ever had."

On how he sleeps at night

"The reality is that we've made an immense amount of progress through sensible policies over the years. More than half of all the countries that once had potential nuclear bomb material on their soil have gotten rid of it. We've reduced nuclear weapons by more than 80 percent around the world. We've managed to avoid nuclear conflict and put in place sensible arms restraint measures, with verification, and bit by bit we're making those stronger."

On why the work is so satisfying

"I've had the experience in my career of making a suggestion, convincing governments to try to pursue that suggestion and seeing it make the world a safer place. I really think there's almost nothing more satisfying than that experience. My father had that experience as well. He was one of the key negotiators, perhaps the most important of the US negotiators, of the most important nuclear arms treaty of all time, the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. So it's a satisfying life if you can actually make some progress and I feel like we have."

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled Bernard Brodie’s name.

This story was produced, in part, with support from the N Square Collaborative.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!