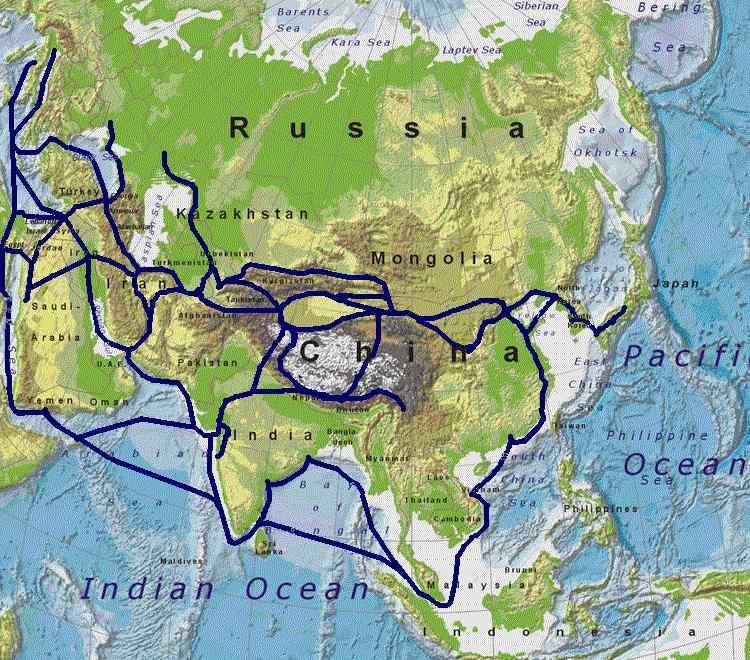

Josh Kucera is traveling along the length of the border between Europe and Asia, from Turkey'sBosphorus to Russia's Arctic, to see how ideas of European or Asian identity profoundly affect the politics and geopolitics of the people who live along it.

I'm in a village called Fatmayi of Absheron, in Azerbaijan. My left foot is in Asia and my right foot is in Europe.

It doesn't really feel like I'm on a continental boundary here. I'm standing in what's basically a dump of discarded construction materials on the side of a somewhat busy road, but there's also a marker that the Azerbaijan Geographical Society put up three years ago identifying what they say is now the border between Europe and Asia.

There's no consensus on where exactly the border between Europe and Asia goes. Most accept that the border crosses somewhere between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. But a lot of the variations place Azerbaijan entirely in Asia. This doesn't fit very well with Azerbaijan's sense of itself.

They like to think of themselves as at least partly European (the Eurovision Song Contest was held here in 2012). And so this new border the Azerbaijanis have created would place about one-sixteenth of their country inside Europe.

The border between Europe and Asia has a long and fascinating history — and it continues to affect countries surrounding it.

Currently, Turkey is wrestling with the legacy of the forced Westernization of Ataturk, snubs by the European Union, and a confident, rising Muslim middle class.

Georgia is trying to break free of its history of Russian control by asserting a European identity and aspirations to join the EU and NATO.

Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan have developed ambitious nation-building programs around "Eurasian" identities, as they try to associate themselves with both the prestige of Europe and the dynamism of Asia.

And Russia has forcefully revived its age-old debate about where it really belongs vis-a-vis Europe.

The Europe-Asia border was first defined by the ancient Greeks, and even then it was fairly arbitrary.

For example, Herodotus wrote about the border but said he didn't even know why the continents divided this territory — a territory that was obviously one unitary land mass, and to the ancient Greeks, there really wasn't any meaning to Europe and Asia. They were just purely geographical terms.

Of course today, that's no longer the case. When you say Europe, all sorts of cultural, political, and geopolitical associations come along with that — even more so when you talk about the West, which people often use interchangeably with Europe.

Associations with "the West" include things like civilization, enlightenment, democracy, individualism, and materialism — while "Asia" or "the East" has been associated with the opposite of all those things.

The thing that's most interesting to me is that these countries along this artificial, geographical border are exactly those where you have some of the most profound and serious debates about national identity: Where do we fit? Are we European? Are we Western? Are we Eastern?

The best-known examples of these are Ataturk in Turkey and Peter the Great in Russia.

Most geographers will tell you it's useless to try to define exactly where the border between Europe and Asia lies. They'll agree with Herodotus: that it's an artificial distinction, and that if you want to think about continents it makes more sense to think about one continent, Eurasia, rather than dividing it into two parts.

But geographers occasionally have made efforts to try to redefine the border, usually in connection with politics.

Under Peter the Great, Russian geographers fixed the eastern border of Europe at the Ural Mountains, and this was closely connected to his efforts to try to make Russia into a European country. Soviet geographers in the 1950s and '60s tried again to redefine the border, also a politicized effort: Russians didn't believe that Muslims were Europeans, so they drew the border between Europe and Asia well north of Azerbaijan.

Who knows — it may be that geographers from all of the Europe-Asia border countries will have to convene some sort of congress to determine, among themselves, the proper border. But as of now, the prospects for that are uncertain.

Journalist Josh Kucera is traveling along the length of that border, from Turkey's Bosphorus to Russia's Arctic. Supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, Kucera is investigating how ideas of European or Asian identity profoundly affect the politics and geopolitics of the people who live along it.