Maria da Conceicao Queiroz da Silva, 41, was evicted from Vila Autodromo, where she lived for 19 years, because of the 2016 Rio Olympic Games.

Maria da Conceicao Queiroz da Silva was shocked by how fast the tractor took down her house.

The 41-year-old Brazilian babysitter has lived in Rio de Janeiro’s Vila Autodromo community for 19 years. But the community sits on the edge of the new Olympic Park, and her house recently became one of about 500 area homes that were demolished to make room for an access route to the sporting facility.

As many as 2,548 families — around 10,000 people — from 16 communities around Rio were forced to leave their homes because of construction projects linked to the 2016 Summer Olympics, according to an independent report by a community rights network of researchers, students, workers and residents. The projects are considered part of the legacy that the games will leave the city: two bus rapid transit lines and revamps in areas around the Maracana soccer stadium and the Rio harbor.

For four months, Brazilian investigative journalism agency Agencia Publica reported on the Olympic evictions, interviewing more than 60 families. The impact was harsh: Many displaced families lost jobs, spots in local schools and a chance to easily access the public services and wonders of the city, such as the beach itself.

In most cases, families said they had no choice but to leave. They fret about ending up on the streets if they don’t accept one of the government's offers: rent assistance, indemnity or an apartment in a federal housing project, sometimes up to 25 miles away from their original neighborhood. All around the city, community ties were broken and the interaction with neighbors and family was hampered.

Silva says she misses getting home after a tiring day at work and feeling welcomed by her friends. “You could sit outside, chat with the neighbors, have a barbecue in front of your house….” Even though some old neighbors live in the same condo, she feels isolated in her new home: a small, dark apartment in Parque Carioca housing project.

Vila Autodromo residents fiercely resisted the evictions and were supported by local artists, activists and universities. But City Hall was determined to make them leave. The low-income community was an obstacle in the future of its elite neighbors: Once the games are over, big construction companies will turn the Olympic Park and the Athletes’ Village into luxury condos on the edge of the Jacarepagua lake. The enterprise will match the real-estate valuation of the Barra da Tijuca region, where land is 140 percent more expensive now than in 2009, when the 2016 Rio Games were announced.

Silva remembers receiving 19 phone calls in one day to go to City Hall and negotiate compensation. Residents said officials used fear as a strategy to force them out of their homes: In June 2015, Rio police assaulted residents while trying to demolish a house. Images of bloody heads and rubber bullet-injured arms were all over the internet.

The city's law enforcement office said residents attacked officials with rocks and the police intervened, according to the G1 news website.

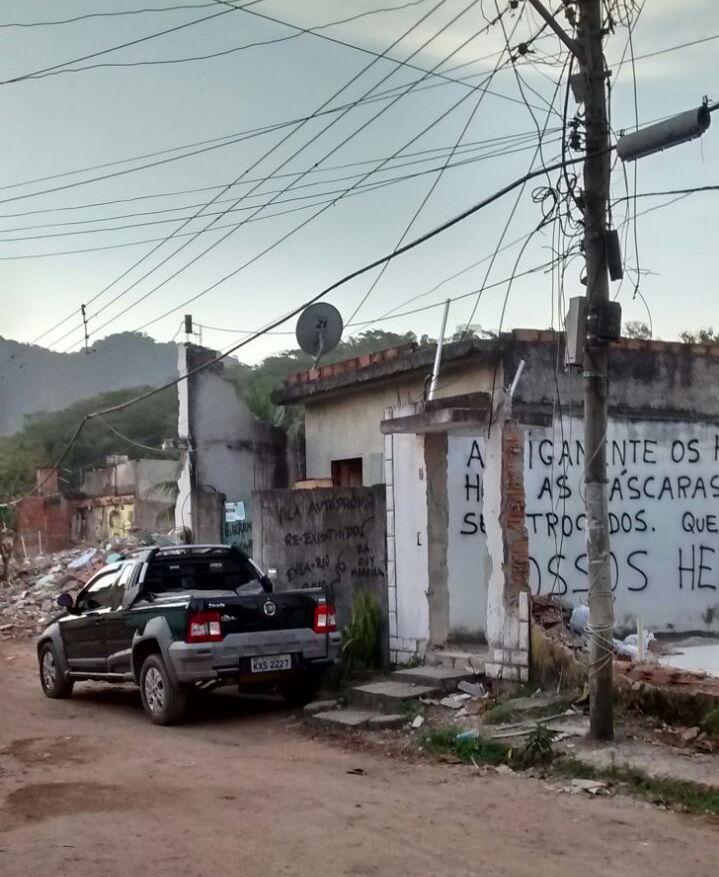

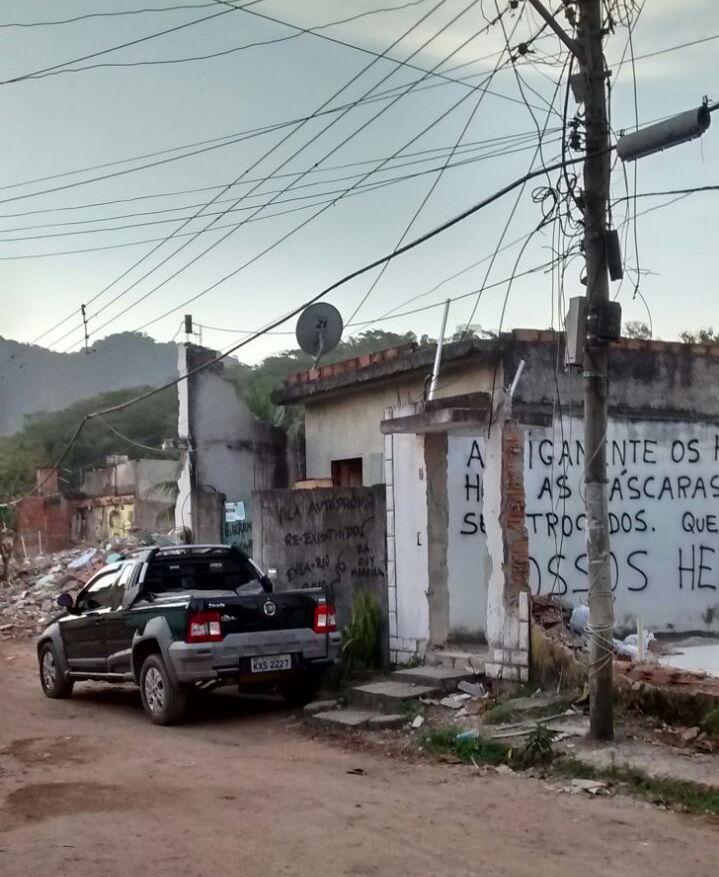

In the end, Silva’s house was surrounded by garbage and debris from her old neighbors’ houses, which were instantly razed once compensation was negotiated. “There were water and light shortages. It was scary, it looked like a true war zone.” The pressure forced Silva to leave Vila Autodromo in April.

Today, just outside the Olympic Park, a small cluster of houses sits on otherwise empty land, where more than 500 families’ homes once stood. City Hall built the cluster for the families who refused to leave — a small yet symbolic victory for a few Vila Autodromo residents.

For Silva, it’s proof that the community could have stayed beside the Olympic facilities. “They never gave us the option: If you stay we will urbanize the community,” she says, frustrated that the month-long event displaced her from a 19-year-old home.

This story is part of the Project 100, which aims to gather stories of 100 families forcibly evicted by the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. Led by a team of female reporters from the Brazilian investigative journalism agency Agencia Publica, the project can be seen here: apublica.org/100.

Maria da Conceicao Queiroz da Silva was shocked by how fast the tractor took down her house.

The 41-year-old Brazilian babysitter has lived in Rio de Janeiro’s Vila Autodromo community for 19 years. But the community sits on the edge of the new Olympic Park, and her house recently became one of about 500 area homes that were demolished to make room for an access route to the sporting facility.

As many as 2,548 families — around 10,000 people — from 16 communities around Rio were forced to leave their homes because of construction projects linked to the 2016 Summer Olympics, according to an independent report by a community rights network of researchers, students, workers and residents. The projects are considered part of the legacy that the games will leave the city: two bus rapid transit lines and revamps in areas around the Maracana soccer stadium and the Rio harbor.

For four months, Brazilian investigative journalism agency Agencia Publica reported on the Olympic evictions, interviewing more than 60 families. The impact was harsh: Many displaced families lost jobs, spots in local schools and a chance to easily access the public services and wonders of the city, such as the beach itself.

In most cases, families said they had no choice but to leave. They fret about ending up on the streets if they don’t accept one of the government's offers: rent assistance, indemnity or an apartment in a federal housing project, sometimes up to 25 miles away from their original neighborhood. All around the city, community ties were broken and the interaction with neighbors and family was hampered.

Silva says she misses getting home after a tiring day at work and feeling welcomed by her friends. “You could sit outside, chat with the neighbors, have a barbecue in front of your house….” Even though some old neighbors live in the same condo, she feels isolated in her new home: a small, dark apartment in Parque Carioca housing project.

Vila Autodromo residents fiercely resisted the evictions and were supported by local artists, activists and universities. But City Hall was determined to make them leave. The low-income community was an obstacle in the future of its elite neighbors: Once the games are over, big construction companies will turn the Olympic Park and the Athletes’ Village into luxury condos on the edge of the Jacarepagua lake. The enterprise will match the real-estate valuation of the Barra da Tijuca region, where land is 140 percent more expensive now than in 2009, when the 2016 Rio Games were announced.

Silva remembers receiving 19 phone calls in one day to go to City Hall and negotiate compensation. Residents said officials used fear as a strategy to force them out of their homes: In June 2015, Rio police assaulted residents while trying to demolish a house. Images of bloody heads and rubber bullet-injured arms were all over the internet.

The city's law enforcement office said residents attacked officials with rocks and the police intervened, according to the G1 news website.

In the end, Silva’s house was surrounded by garbage and debris from her old neighbors’ houses, which were instantly razed once compensation was negotiated. “There were water and light shortages. It was scary, it looked like a true war zone.” The pressure forced Silva to leave Vila Autodromo in April.

Today, just outside the Olympic Park, a small cluster of houses sits on otherwise empty land, where more than 500 families’ homes once stood. City Hall built the cluster for the families who refused to leave — a small yet symbolic victory for a few Vila Autodromo residents.

For Silva, it’s proof that the community could have stayed beside the Olympic facilities. “They never gave us the option: If you stay we will urbanize the community,” she says, frustrated that the month-long event displaced her from a 19-year-old home.

This story is part of the Project 100, which aims to gather stories of 100 families forcibly evicted by the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. Led by a team of female reporters from the Brazilian investigative journalism agency Agencia Publica, the project can be seen here: apublica.org/100.