Punks Fight Law and Law Wins

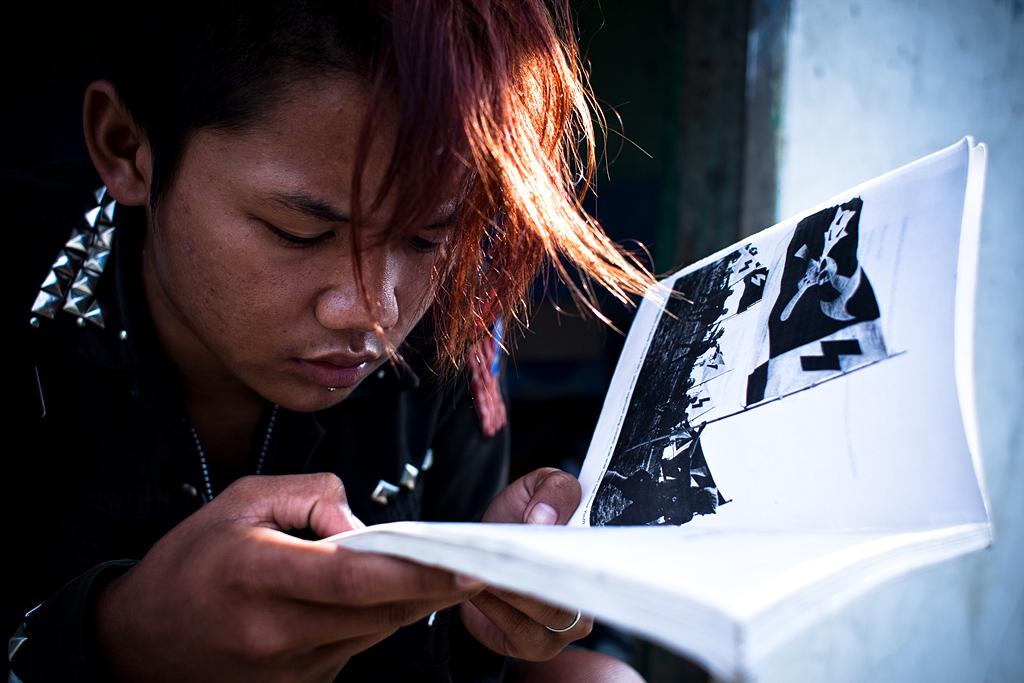

A punk member reads a book about history of Punk, Banda Aceh, Aceh Province, Indonesia.

BANDA ACEH, Indonesia — Since its birth in the 1970s, punk culture has spread to every corner of the world, including this far-flung and religiously devout provincial capital in Indonesia. Growing up as a punk kid in Banda Aceh is not easy. In a city governed by Sharia, or Islamic, law, 20-year-old Sandi, who is known by his friends as Scooby, is not as lucky as his punk brothers in other parts of Indonesia. In the capital city of Jakarta, where the punk community is large and vibrant, punks are often more free to express their identity, style and ideas. This is not the case in Aceh. “I remember when we were suddenly being chased and arrested by the Sharia police,” Sandi said, recalling a raid on the punk community earlier this year. Sandi is a member of Museum Street Punk, one of Aceh’s largest punk communities. In recent months, he and his friends have become the latest target of the province’s controversial Sharia police. Sandi spent a week in detention until his parents were able to secure his release. During that time, he suffered one of the biggest indignities for any punk — his mohawk was shaved off by the authorities. Marzuki, the head of investigations for the Sharia police, and who goes by only one name, said the punk culture violates social norms and the Islamic dress code, violating Sharia law. He adds that some punks have also been involved in brawls, drugs and crime. It’s a refrain that’s been hurled at the punk community the world over for decades. “We receive instruction from the governor and the mayor of Banda Aceh to discipline these kids,” he said, adding that young punk communities were a public nuisance. “We didn’t detain these kids, we rehabilitated them … They would be released when their parents picked them up, but the parents asked us to prolong the rehabilitation instead because they have been unable to knock sense into their kids, who have been influenced by this punk culture,” Marzuki said. He also said that the Sharia police only shaved their hair with the consent from their parents. Sandi bristles at the idea that he was being labeled a criminal based on his look. “Don’t judge us by our look. This is only a style,” he said. Azhari, a cultural observer and writer, regrets that many people in Aceh, including the government are not ready to embrace a more open, accepting society. “The children in Aceh are in danger of failing because there is no support for youth activities,” he said.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!