Opinion: clash of generations in the Mideast

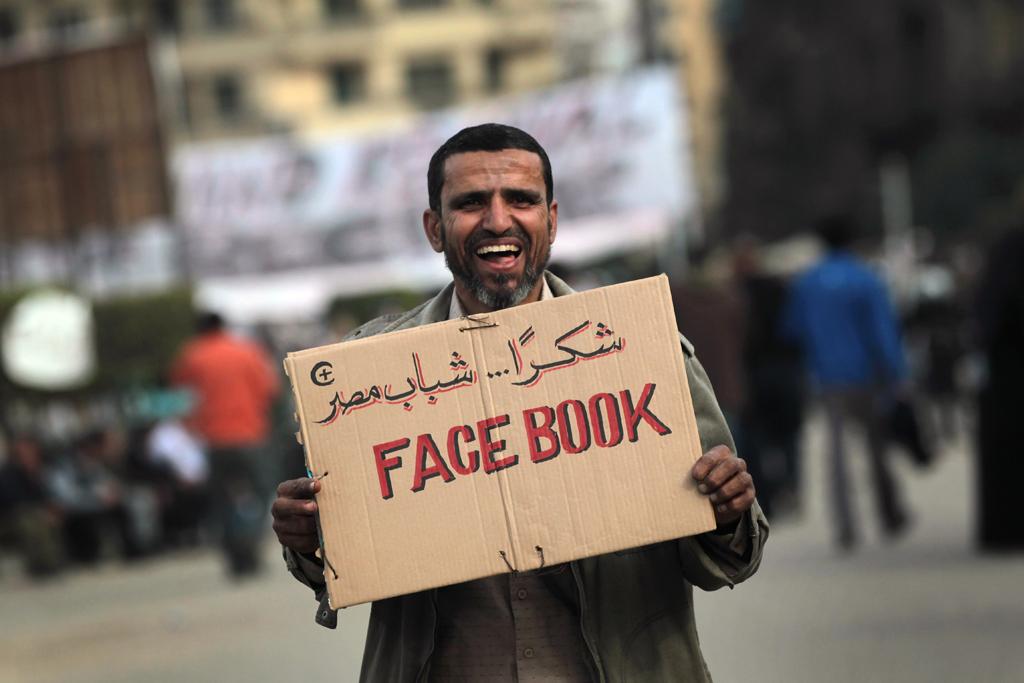

An anti-government demonstrator holds a sign during clashes on Feb. 3, 2011 in Cairo, Egypt.

BOSTON — After the recent events sweeping the Middle East, were Harvard’s Samuel Huntington alive today, he might consider an addendum to his seminal “Clash of Civilizations” called: The Coming Clash of Generations. The original ”Clash” foresaw that the great battles of ideology were passing, and that civilizational conflicts would rise to take their place. And in the case of much of the Muslim world his work was prescient.

But “Clash” was written before the full impact of the computer age was upon us. Nobody could foresee how much a new generation would take to a new technology, expanding its possibilities, and never looking back as it trampled out the old.

The events in Egypt transcended Islam and the West, and were was put in motion by young, technologically savvy Arabs in different countries who got together by social networking, transcending borders, in a manner that their elders neither understood nor knew how to combat. In Tahrir Square the barriers between Christian and Muslim, secular and devout, seemed to melt away. Civilizations seemed to unite out there in the square with the young, as the barriers between young Egypt and old Egypt began to rise.

In Washington the same clash was taking place. The old foreign policy mandarins were advising U.S. President Barak Obama to go slow, don’t withdraw your support from Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak — chaos might follow, they said. Foreign leaders, such as Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu and King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, were among the most insistent that the United States should stick with Mubarak. And who could represent old thinking better than Netanyahu and the king of Saudi Arabia?

According to the New York Times, Obama took a different view. This was a trend that could spread and grow, the president thought, and what could undercut Al Qaeda’s narrative more than a peaceful change of power in Egypt, the home of the No. 2 Al Qaeda leader, Ayman al Zawahari? It was a change of power in “the near enemy,” as Zawahari calls the Middle Eastern countries, without the interference of the “far enemy,” the United States. It was a change of power devoid of terrorism and of little violence, a change of power that was by the people and for the people and not by and for the West.

Of course the old generation may not be completely down and out in Egypt or elsewhere. To be honest, an army coup is not the revolution the new generation has in mind. A Robespierre or a Lenin, or even an ayatollah, may be waiting in the wings. And the young, so good at networking and harnessing dissent, may not prove to be so apt at governing. They may not be given the chance. One of the major failings of this movement is that protestors may know what they don’t want, but have had trouble articulating what, and whom, they do want.

But something new is taking place in the Middle East in the relationship between those who govern and the governed.

There have been generational splits before, of course. One of the deepest came after World War I when “flaming youth” and the flapper generation upset the tables of the Edwardian era. But seldom has the generational split so involved, and been dominated by, a new technology as this one in which new worlds are opening so quickly to the young — worlds that are denied to those who haven’t the skills. These are the elites, of course. Only about 20 percent of Egyptians have access to the internet.

In generations past the old were expected to instruct their children, but in today’s world it has become a cliche that seniors have to call upon the young to help them find their way in brave new cyber world.

A glaring example of the clash of generations took place when Obama spoke to Mubarak by telephone in the old man’s last days in power. “I respect my elders,” said the young American president, “and you have been in politics for a very long time. … But there are moments in history when just because things were the same way in the past doesn’t mean they will be that way in the future.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!