“Harare Spring” fizzles

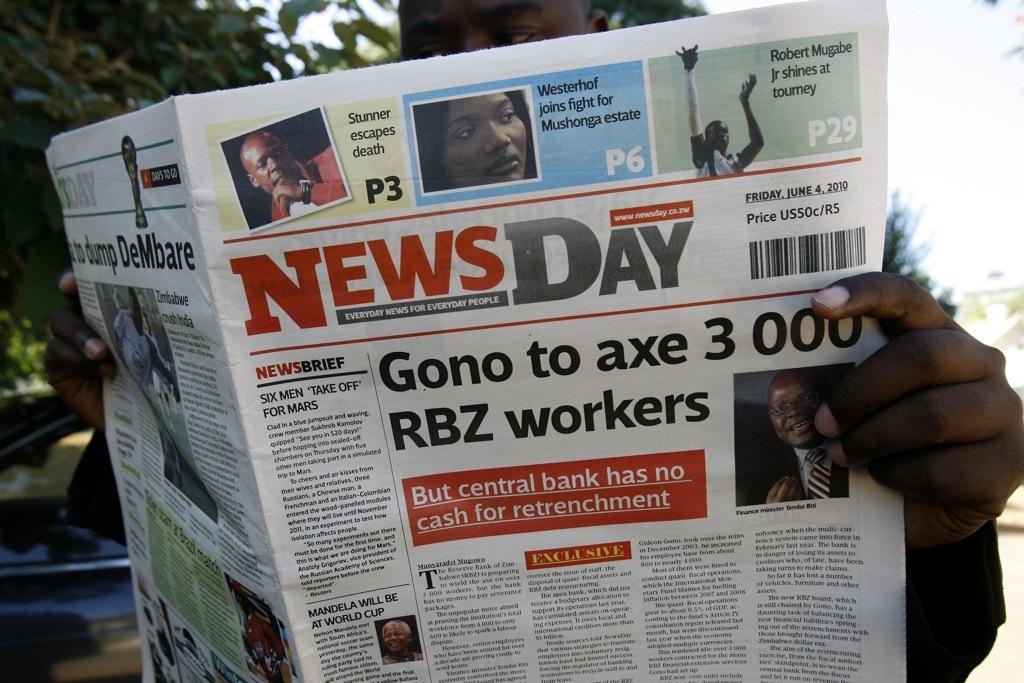

NewsDay is one of the new, privately owned newspapers that President Robert Mugabe has permitted to print in the past year, but the government has refused to allow more press freedom.

HARARE, Zimbabwe — “Publish and be damned” is more than just an expression in Zimbabwe today, where the news media is restricted and under threat.

President Robert Mugabe's government has issued licenses to a raft of new newspapers, as a result of agreements between the major parties following flawed elections in 2008.

Among the new batch of publications are NewsDay, a daily published by Alpha Media Holdings which also publishes the Zimbabwe Independent and Standard.

Another prominent new publication is the Daily News, owned by Associated Newspapers of Zimbabwe, which was closed down in 2003 for failing to comply with the registration clauses in the most notorious of Mugabe’s media laws, the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (Aippa). Prior to that, the company’s printing press was destroyed in a bomb attack. Despite the state’s ubiquitous intelligence service nobody was ever charged.

The new privately owned newspapers have provided a measure of diversity but the “public” media remains in the tight grip of the state’s unforgiving propaganda apparatus.

Government-owned papers have exploited their hitherto dominance on the market to act as cheerleaders for Mugabe, 87, and to denigrate Movement for Democratic Change leader Morgan Tsvangirai. The two are currently locked in South African-backed talks on a new constitution. But Mugabe has used the negotiations, now in their third year, to block agreed upon changes and claw back power lost in the 2008 poll. Most notably he has used the police, army and intelligence service to prop up his unpopular regime.

Journalists have been arrested and detained for “undermining the authority” of the president and for publishing the names of state officials responsible for torturing civic detainees, names that had already appeared in court papers.

Despite the proliferation of new publications, Mugabe's regime has refused to open up the airwaves. As a result the only voice heard across the land is Mugabe’s. There also remains on the statute book a host of measures that impinge on press freedom.

“Zimbabwe’s media environment remains threatened by legal and administrative impediments,” United States ambassador to Harare, Charles Ray, told a gathering on Press Freedom Day, May 3. “Journalists and publishers continue to be under threat for doing their work with increased self-censorship for fear of criminal defamation suits.”

Zimbabwe’s criminal defamation laws are a relic of empire, designed to muzzle voices of insurgent nationalism throughout Britain’s far-flung dominions. Most former colonies have repealed such legislation on the grounds that it is inconsistent with democratic norms. Currently, senior MDC official Roy Bennett is unable to return to Zimbabwe to take up his government post because the threat of prosecution hangs over him.

Mugabe's Media and Information Minister Webster Shamu has called on Zimbabwean journalists working in the diaspora to return home. He has also urged what the government calls “pirate” radio stations transmitting to Zimbabwe from abroad to close down. But editors have said the state must guarantee a speedy and unobstructed passage for those who want to return and an end to hate-mongering in the state media.

Currently MDC leaders are subject to vitriolic attacks by the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC) and are denied the right of reply. The national broadcaster has in recent weeks been attempting to shift responsibility for violence to the MDC. But Bennett has rejected this claim as ridiculous.

“What we have in Zimbabwe,” he told a business meeting in London, “is a ruthless coterie of thugs, bullies and incompetent individuals masquerading as a political organization.”

Zimbabwean human rights lawyer Beatrice Mtetwa believes ZBC is incapable of reform. Focus should instead be on newcomers, she said.

“I doubt that ZBC in its current state and in our current political environment can be transformed,” she said on Press Freedom Day. “The route we ought to be taking is not transformation of ZBC but providing serious competition to ZBC.”

Media practitioners want the Zimbabwe Media Commission, which is responsible for the licensing of newspapers and broadcasters, to be more proactive in removing media laws that obstruct new players. They point out that it is now two years since state and private media representatives met at the lakeside resort of Kariba to thrash out reforms. There was consensus that Aippa should go.

But that brief "Harare Spring" has fizzled out as the state confines itself to licensing a handful of papers ahead of elections next year, and refuses to permit independent voices on the airwaves.

What is clear from all this is that the public will be unable to make an informed choice at the ballot box. As that is what democracy is all about, Zimbabwe’s future remains bleak in the short term.