“Moscow, December 25, 1991”: A bucketful of filth

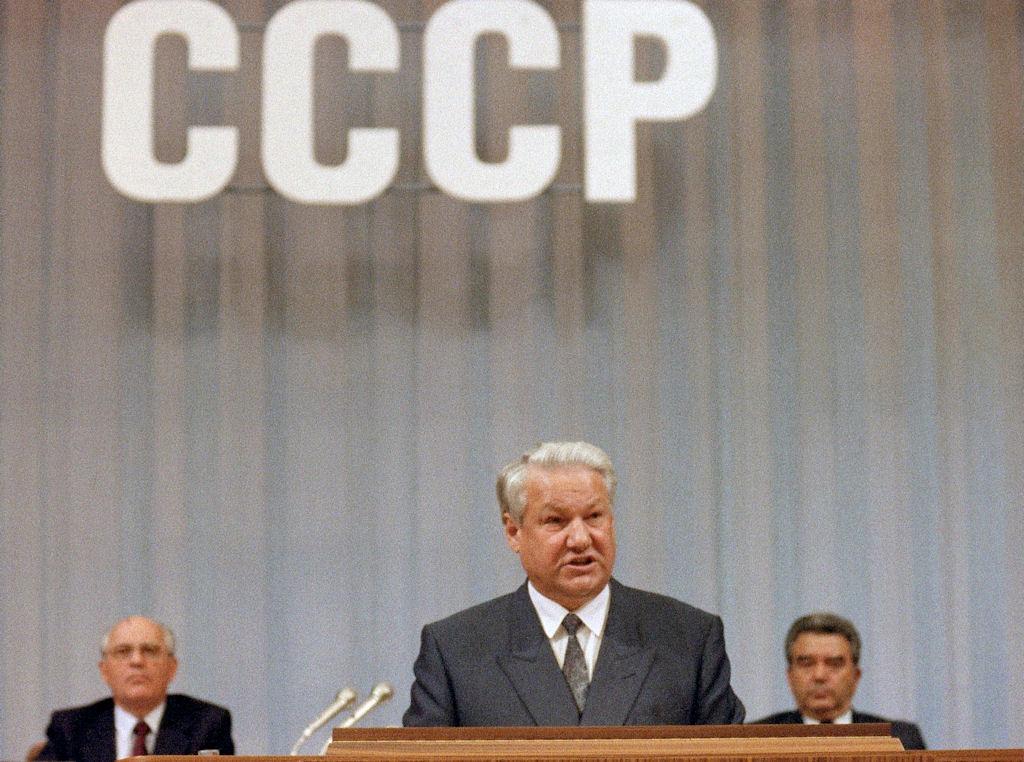

Russian President Boris Yeltsin addresses the deputies at the People’s Congress in Moscow, as Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev (left) listens in the background, on Sept. 3, 1991.

This is the second excerpt from Conor O'Clery's new book, "Moscow, December 25, 1991: The last day of the Soviet Union." The first part introduces the enormity of what two leaders accomplished that day. The third part explains how Yeltsin began the climb to leadership of Russia, from where he was able to bring down Gorbachev.

The three hundred members of the Central Committee converged on a raindrenched Kremlin early on Oct. 21, 1987 without any sense that a blowup was imminent. They stepped out of their Zils and Chaikas and hurried into the e18th-century Senate Building. Here, in rows of ornate chairs beneath the stony gaze of 18 prerevolutionary poets portrayed in bas-relief among the white Corinthian columns and pilasters high above, they awaited the single item on the agenda: General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev reading his prepared speech. The 14 Politburo members sat in a line behind a desk on a raised podium, facing the assembly.

Yeltsin took his place in the front row along with the half dozen other Politburo candidate members and various senior party officials. The meeting was closed to the media. By convention the advance speeches of the general secretary would be approved by acclamation, and everyone would retire to enjoy a pleasant lunch.

Yegor Ligachev, the member of the Politburo who had recommended Yeltsin be brought to Moscow, presided. He called on Gorbachev to speak. The general secretary outlined his presentation. After 30 minutes he finished, and Ligachev asked, “If there are no questions . . . ?” Yeltsin hesitantly raised his hand, then took it down, as if he were of two minds. Gorbachev pointed him out to Ligachev, who asked if members wanted to open debate on the speech. There were cries of “No!” Slowly the big man from Sverdlovsk stood up, his intuition to speak out winning out over the pressure to conform. Ligachev signaled to him to sit down. But Gorbachev intervened. He would give Yeltsin enough rope to hang himself. “I believe Boris Nikolayevich wishes to say something,” he remarked icily.

Yeltsin seemed nervous and ill prepared. He spoke for about seven minutes in a disjointed fashion, using notes jotted hastily on his voting card. Nevertheless, the thrust of his argument was clear. The promise of perestroika was raising unrealistic expectations that could give rise to disenchantment and bitterness. He was deeply troubled by “a noticeable increase in what I can only call adulation of the general secretary by certain full members of the Politburo. I regard this as impermissible … . This tendency to adulation is absolutely unacceptable … . A taste for adulation, which can gradually become the norm again, can become a cult of personality. We cannot permit this.” Besides, the opposition to him from Comrade Ligachev was such that he must resign from the Politburo, he said. As for his leadership of the Moscow Communist Party, “that of course will be decided by a plenum of the city committee of that party.”

This was sensational. Besides the fact that no one ever quit the Politburo, no one in the party had ever had the audacity to address a leader in such a manner in front of the Central Committee since Leon Trotsky in the 1920s. In the opinion of Anatoly Chernyaev, a senior advisor to Gorbachev, “Such a brazen attack on the holiest of holies — on the Central Committee secretariat, on the number two person in the party, and on the general secretary himself — was truly scandalous.” Yeltsin rationalized later that, “Something had to be changed in that putrid system.” The general secretary had reverted to being equivalent to the tsar, father of the people, and to express the slightest doubt about his actions was an unthinkable act of sacrilege. “One could express only awestruck admiration … or delight at being so fortunate as to be able to work alongside him.”

There was a stunned silence as Yeltsin sat down, his heart pounding, “ready to burst out of my ribcage.” He knew what would happen next. “I would be slaughtered in an organized, methodical manner, and it would be done almost with pleasure and enjoyment.” It is doubtful, however, that he was ready for it.

Valery Boldin, Gorbachev's chief of staff, saw the general secretary's face go purple with rage. The suggestion that the he aspired to greatness through a cult of personality had hit a nerve.

“Perhaps it might be better if I took over the chair,” said Gorbachev. “Yes, please do, Mikhail Sergeyevich,” said Ligachev hastily.

Gorbachev coldly summed up Yeltsin’s speech and suggested that their comrade was seeking to split off the Moscow party organization from the party as a whole. When Yeltsin tried to interject, Gorbachev told him brusquely to sit down and called for comments from the floor.

This was the signal for a sustained assault. Sycophants and toadies, some of them victims of Yeltsin’s purges in Moscow, took the microphone one after another to berate the heretic. Gorbachev watched his nemesis as the hammer blows descended. He reflected how Yeltsin himself had put people down meanly, painfully, often undeservedly. Now he read on Yeltsin’s face a strange mixture of “bitterness, uncertainty, regret, in other words everything that is characteristic of an unbalanced nature.”

Some comments Yeltsin found especially hurtful. His one-time mentor in Sverdlovsk, Yakov Ryabov, who was then Soviet ambassador to France, doused him in what he later described as a bucketful of filth. The insults would have been part of the rough and tumble in some Western parliaments, but they were damning in the context of a Central Committee plenum of the tightly disciplined Communist Party in 1987. Even the most progressive Politburo members, Eduard Shevardnadze and Alexander Yakovlev, rallied behind Gorbachev and spoke against the dissenter, something he found especially painful. Some denunciations were predictable. Viktor Chebrikov, head of the KGB, berated him for blabbing to foreign journalists. He was dismissed by others as clueless, someone who distorted reality, suffered delusions of grandeur, and was guilty of political nihilism. A few speakers unwittingly proved his point about Gorbachev’s cult of personality. “As to the glorification of Mikhail Sergeyevich, I for one respect him with all my soul both as a man and as a party leader,” declared regional secretary Leonid Borodin, with no trace of irony.

Twenty-seven speakers spent a total of four hours beating up on their quarry before Gorbachev brought the vilification to an end. Yeltsin meekly asked for the floor again. As had happened before, he was utterly overwhelmed. All his bravado had evaporated. He tried to be conciliatory. He never had any doubts about perestroika, he stammered. He agreed with much of what had been said about him. He had only two or three comrades in mind who went overboard with praise for the general secretary.

Gorbachev cut in. “Boris Nikolayevich, are you so politically illiterate that we must organize an ABC of politics for you here?” “No, there is no need any more,” he replied. Gorbachev twisted the knife. He accused his challenger of being “so vain and so arrogant” that he put his personal pride above the party and of having a puerile need to see the country revolve around his persona. And at such a critical stage of perestroika!

When Gorbachev had finished, Yeltsin mumbled, “In speaking out today, and letting down the Central Committee and the Moscow city organization, I made a mistake.”

Unexpectedly Gorbachev offered Yeltsin a chance to undo the damage. “Do you have enough strength to carry on with your job?” he asked. “I can only repeat what I said,” replied Yeltsin, to catcalls. “I still request that I be released.” Gorbachev proposed that he be censured for his politically incorrect tirade. The motion was passed unanimously. Even Yeltsin voted in favor. A few days later he wrote a letter to the general secretary expressing his wish to continue in the job as Moscow party chief. Chernyaev cautioned his boss: “The stakes are high. The supporters of perestroika among the so-called general public are on Yeltsin’s side.” But Gorbachev called his critic on the telephone to say bluntly, “Nyet!”

News of a rupture in the Politburo soon began to leak. Rumors about Yeltsin’s “secret speech” at the Central Committee spread throughout Moscow. Fabricated versions began appearing. One was concocted by his editor friend Mikhail Poltoranin. In this version Yeltsin complained that he had to take instructions from Gorbachev’s wife, Raisa, though he had said no such thing. Poltoranin distributed hundreds of copies, and they became part of samizdat, underground literature that the official media would not print.

On Nov. 7, 1987, the 70th anniversary of the October Revolution, Gorbachev and fellow members of the Politburo welcomed fraternal world leaders in Red Square to watch a military parade of goose-stepping soldiers and tanks belching diesel smoke.

Yeltsin was ignored by his comrades as they lined up on top of the Lenin Mausoleum, but diplomats, correspondents, and foreign visitors could not take their eyes off him. The small revolt in the formidable ranks of Soviet communism was world news. Fidel Castro gave him a big hug, three times, and General Wojciech Jaruzelski of Poland embraced him, saying in fluent Russian, “Hang in there, Boris!” At a Kremlin reception for diplomats, American ambassador Jack Matlock noticed Yeltsin standing apart with a rather sheepish smile, shifting his stance from one foot to another, “like a schoolboy who has been scolded by his teacher.” The Moscow party chief smiled at him. The envoy kept his distance. The last thing Yeltsin needed was to be seen conversing with the American ambassador.

Political drama turned to ugly farce. Gorbachev called a meeting of the Moscow branch of the Communist Party for Wednesday, Nov. 11, to confirm Yeltsin’s dismissal as party leader of the capital city. Two days before the meeting, on Nov. 9, Yeltsin apparently tried to kill himself. He was rushed to the special Kremlin hospital on Michurinsky Prospekt on the outskirts of Moscow, bleeding profusely from self-inflicted cuts to his chest. By his account, “I was taken to hospital with a severe bout of headaches and chest pains … . I had suffered a physical breakdown.” At their apartment Naina took the precaution of removing knives, hunting guns, and glass objects, as well as prescription medicines, in preparation for his return.

Gorbachev took the attitude that the Siberian rebel was faking to draw attention to himself and avoid the showdown. “Yeltsin, using office scissors, had simulated an attempt at suicide,” he concluded. “The doctors said that the wound was not critical at all; the scissors, by slipping over his ribs, had left a bloody but superficial wound.” On the morning of the Moscow meeting he telephoned Yeltsin in his hospital room and told him to get dressed and come to the plenum of the Moscow city committee that would decide his future. “I can’t. The doctors won’t even let me get up,” protested Yeltsin. “That’s OK, the doctors will help you,” replied Gorbachev.

Acting on party orders, a Kremlin physician, 41-year-old Dmitry Nechayev, gave his patient a strong dose of a pain reliever and antispasm agent called baralgin. He “started to pump me full of sedatives,” recalled Yeltsin. “My head was spinning, my legs were crumpling under me, I could hardly speak because my tongue wouldn’t obey.” Yeltsin decided not to resist. He hoped that someone would speak up for him at the assembly.

Naina, his wife, objected furiously to the overall head of security for Soviet politicians, General Yury Plekhanov, who was at the hospital, that discharging a sick man amounted to sadism. But Plekhanov answered to a higher authority.

Alexander Korzhakov, Yeltsin's security chief, assisted his charge, dazed, bandaged, and with his face swollen, to a car and drove him the six miles along Leninsky Prospekt and through the city center to Old Square. The setting was a long, narrow, whitewashed chamber in the Central Committee building. Yeltsin was brought barely conscious to an adjoining room, where the Politburo members had gathered to make an impressive entrance.

When everyone was seated, they walked grimly onto the stage, like judges in a courtroom. Yeltsin trailed in behind them. The KGB had sealed off the front rows of seats for members who had put down their names to speak. They were, observed Yeltsin, mostly Moscow cadres who had been sacked in the previous year and a half and were waiting like “a pack of hounds, ready to tear me to pieces.” The Politburo members sat in three rows of chairs behind a long table, facing the hall.

Gorbachev got straight to the point. They were there to discuss whether to relieve their colleague of his duties as Moscow party chief. “Comrade Yeltsin put his personal ambitions before the interests of the party,” he said. “He made irresponsible and immoral comments at the Central Committee meeting.” He mouthed appeals and slogans, but when things went wrong, he manifested “helplessness, fussiness, and panic.”

One by one members of the Moscow party organization rose to follow Gorbachev’s lead and accuse the drugged and dazed Yeltsin of everything from overweening ambition, demagoguery, lack of ethics, and ostentation to blasphemy, party crime, and pseudorevolutionary spirit. Twenty-three speakers once more savaged him over the course of four hours. Only the Moscow party second secretary, Yury Belyakov, praised the collegiality, open criticism, and exchange of views that Yeltsin encouraged. One member sneered, “We’ll see people who will try to make Jesus Christ out of Boris Nikolayevich.” Another denounced him for treason to the cause of party unity. A third accused him of loving neither Moscow nor Muscovites. Their quarry only occasionally raised his eyes to look in disbelief as a former comrade abused him, and to shake his head when told he did not love Moscow.

Gorbachev grew uneasy at the fury he had unleashed. “Some of the speeches were clearly motivated by revenge or malice,” he conceded in his memoirs. “All of this left an unpleasant aftertaste. However at the plenum Yeltsin showed self control and, I would say, behaved like a man.”

In the tradition of show trials, the accused was permitted to display contrition after all the venom had been spat out and his morale demolished. He stumbled towards the microphone, his lips bluish, with Gorbachev holding his elbow, for the auto-da-fe. There were shouts of “Doloi”—”Down [with him]!”—from the front rows. Yeltsin mumbled incoherently and paused often to catch his breath. He would start a sentence, then lose his train of thought. He tried to salvage a shred of dignity, saying he believed in perestroika but that its progress was patchy. He castigated himself for allowing “one of my most characteristic personal traits, ambition,” to manifest itself. He had tried to check it but regrettably without success. He concluded, abjectly, “I am very guilty before the Moscow party organization … and certainly I am very guilty before Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, whose prestige in our organization, in our country, and in the whole world is so high.”

But inside he felt only bitterness and wrath. Yeltsin would never forgive Gorbachev for his “inhuman and immoral” treatment in dragging him from his hospital bed to be fired in disgrace. “I was dismissed, ostensibly at my own request,” he recalled some years later, “but it was done with such a ranting, roaring and screaming that it has left a nasty taste in my mouth to this day.”

Everyone shuffled off to the exits, leaving their wounded prey alone in the room, sick, exhausted, and distraught, his head leaning on the presidium table. The last to leave the hall, Gorbachev glanced back as he crossed the threshold. He returned and put his arm under Yeltsin’s and accompanied him from the room, prompted, Gorbachev’s aide Andrey Grachev suspected, by pangs of conscience. The noble victor helped the vanquished off the field. Korzhakov got him into the car and rushed the stricken Yeltsin back to his hospital bed.

The job of Moscow party boss was given to Lev Zaikov, the Politburo member in charge of military industries, who boasted to Poltoranin, “The Yeltsin epoch is over.”

Gorbachev hadn’t finished with his troublesome protege. He ordered that a version of the proceedings of the closed Moscow party meeting be published in Pravda. This piece of glasnost was clearly designed to display party disapproval of a maverick, in itself previously sufficient to achieve the demolition of a political career. But it backfired. Yeltsin attracted considerable sympathy from Moscow citizens, who believed he really cared about improving their lives. Several hundred students demonstrated at Moscow University, and crude notices appeared in the metro calling for publication of Yeltsin’s secret speech in October.

Yeltsin waited in his hospital bed for a call from his party leader to find out his fate. He expected that he would be banished from Moscow. But that didn’t happen. Perhaps unwilling to act in the old Brezhnev style, or because he felt that his bullheaded stormer still had a useful role to play, possibly even because he thought it was simply the right thing to do, Gorbachev rang the hospital a week later to offer him another job. Korzhakov brought the telephone to his bedside and heard Yeltsin respond “in a totally defeated voice.” Gorbachev suggested that he take the post of first deputy chairman of the state committee for construction. It was a desk job with no policy input, but he would remain a member of the Central Committee. Yeltsin accepted. Anything was better than to be made a pensioner at 56.

Gorbachev had a warning for his adversary, however. “I’ll never let you into politics again,” he told Yeltsin, before putting down the receiver.

With the passage of time, some of Gorbachev’s loyalists would complain that keeping his accuser in government was his biggest blunder. The general secretary ould protest that he had no hatred or feeling of revenge towards Yeltsin and that despite their power struggles he never lowered himself to his level of “kitchen squabbling.”

(Some years later, after Yeltsin has become president of post-Soviet Russia, he unexpectedly comes across Dmitry Nechayev, the doctor who injected him with drugs so he could be hauled before the Central Committee. He is astonished to learn that he is now personal physician to his prime minister, Viktor Chernomyrdin. According to Korzhakov in his memoirs, Yeltsin never forgave the doctor. “Naina, unable to contain herself, went to get an explanation from the prime minister. Chernomyrdin acknowledged he had not heard of the doctor’s injection of Yeltsin with baralgin but did not remove him from his service after this unpleasant conversation.”

On April 7, 1996, the Interfax news agency reports that Nechayev is shot dead at 2 a.m. by an unknown gunman outside the Kremlin hospital on Michurinsky Prospekt. It is one of 216 contract killings in Moscow that year. No one is ever arrested for the crime.)

Read additional excerpts from "Moscow, December 25, 1991" by Conor O'Clery:

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!