Russia’s opposition: Who could take down Putin?

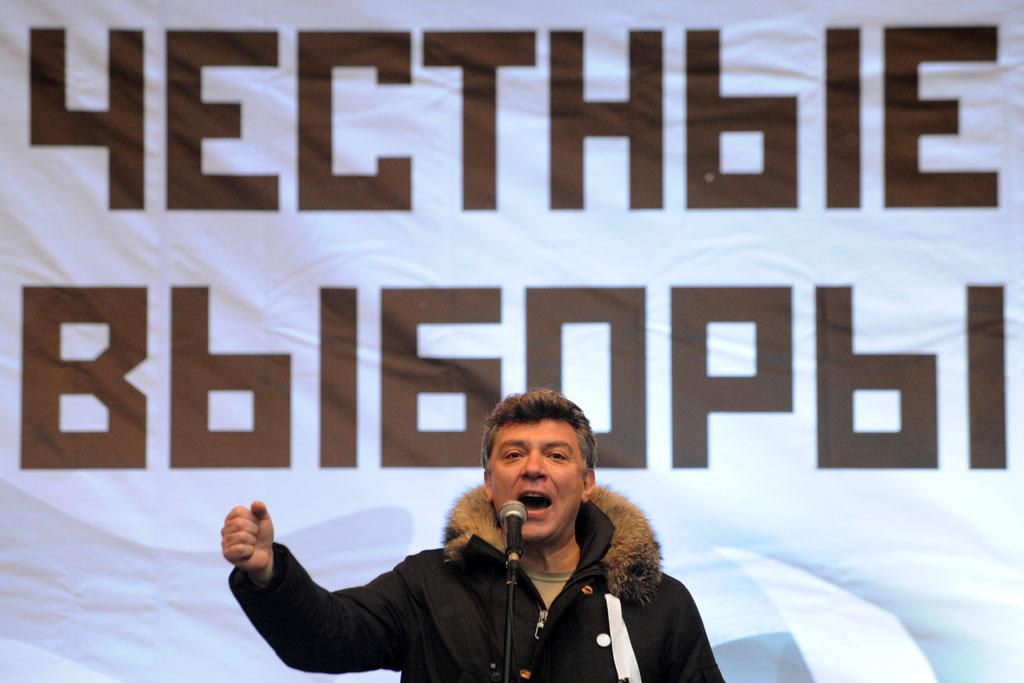

Liberal opposition politician Boris Nemtsov speaks during a rally against the Dec. 4 parliament elections in Moscow, on Dec. 24, 2011.

MOSCOW, Russia — Russians take to the streets Saturday in another wave of street protests against alleged electoral fraud and manipulation.

And with Moscow's Dec. 24 protests, the sense of strong-state stability built by Vladimir Putin over the past decade is beginning to crumble.

No one is ready to count Putin out yet, but his return to the presidency after March polls no longer looks like a sure thing. His once-stratospheric popularity rating plunged to just 51 percent this month. The party that undergirded his power for a decade, United Russia, is in disarray and deeply mired in charges of vote-rigging in the Dec. 4 parliamentary polls.

Some experts are beginning to warn that the system of "managed democracy" — which weeded out independent challengers, limiting choices to those acceptable to the Kremlin — could unravel explosively amid the unpredictable rough-and-tumble of the coming presidential election.

More from GlobalPost: Troops on the streets of Moscow to police post-election protests

That's just a hypothesis, but it's not so far-fetched. In the past century two mighty, autocratic Russian states have collapsed, dragging down their ruling classes and dominant ideology. They were replaced by fresh systems, brought in by new people who arrived in power, in some cases literally, from the streets.

Many experts have warned, with increasing urgency in recent years, that Putin was building a “lite” version of just such a top-heavy, corruption-ridden, muscle-bound Russian state, possessing strong security forces but lacking deep social roots and democratic legitimacy.

People are beginning to ask a previously unthinkable question: If Putin's regime should implode, where might the next wave of leaders come from? Who are they, and what are their agendas?

Like Czarist Russia and the Soviet Union, Putin's Russia has a strictly controlled political system, in which no one is allowed to build an independent political base and bid for leadership from inside the system.

More from GlobalPost: Russia's shrinking population mars Putin's superpower ambitions

Still, Putin's legion of opponents are a diverse, determined and battle-hardened group. They include a blogger, a street agitator, a businesswoman-environmentalist, and ousted political leaders. Many are familiar with oppression, violence and prison. Some live within the system, but others are essentially dissidents, living in constant fear of the secret service. One was even preemptively arrested as the recent protests began.

Putin’s chosen opposition

Putin's "managed democracy" permits a range of tame opposition parties. They accept the Kremlin's rules of the game, in return for the ability to express a range of criticisms and run for parliament and presidency.

They include the Communist Party; the (misnamed) Liberal Democratic Party of ultranationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky; the social democratic Yabloko party; and A Just Russia, a left-wing party that was, ironically, created by the Kremlin in 2006 in hopes that it would displace the Communists.

In any crisis, leaders from these parties might be well placed to seize the reins of power.

More from GlobalPost: Russian protest leaders freed from prison

"A lot depends on whether these so-called systemic-opposition parties can get ahead of the curve," said Nikolai Petrov, an expert with the Carnegie Center in Moscow.

"Their leaders are in a very difficult position. They are compromised by their association with the system for all these years, but now they certainly feel the hot breath of the crowd on their necks. They won some public trust in the elections, but they need to justify it. There is little sign so far that they will."

How to handle the current uprising is a strategically fraught decision for the opposition parties — given that they rely on the Kremlin’s acquiescence to operate freely and to occupy seats in the Duma.

The Communist Party has taken part in rallies to protest vote fraud, but its leaders have been notably absent. Some dynamic members of A Just Russia — such as Duma deputies Ilya Ponomaryov and Gennady Gudkov — have played a key role in organizing the protests and also in trying to assist the 1,000 or so people arrested by police during post-election anti-fraud demonstrations.

But they are hampered by their insistence that an honest recount of the votes from the Duma election is all that's required, and that their parties should be trusted to make the necessary reforms.

"If there were a proper recount, then United Russia would lose its majority," said A Just Russia deputy Ponomaryov. "Then an opposition-dominated Duma could change the election laws and call a new vote. … The vast majority of people who came out to protest on Dec. 10 are not revolutionaries, they are just people who want freedom of choice. But if there were real freedom of choice in Russia, that would be quite revolutionary."

The range of permitted opposition forces also includes metals tycoon Mikhail Prokhorov, who recently declared that he will challenge Putin for the presidency. But Prokhorov is unlikely to appeal to the broad majority of Russians; they despise the "oligarchs" who made shady fortunes in the anything-goes 1990s. Prokhorov may not even be able to overcome middle-class suspicions that he could be a Kremlin stooge.

The real rebels

But pressing at the gates is a full spectrum of "non-systemic" opposition groups, including political parties that have been prohibited by the Putin regime, and some new people whose names were little known, even in Russia, until the protest movement propelled them into the public limelight.

Most of these unsanctioned opposition groups demand that the Dec. 4 elections be cancelled and completely reorganized under fair conditions for all.

Parnas: the banned liberal party

For the Moscow middle class — the biggest social group to take to the streets so far — the main pole of attraction could be Parnas, a banned liberal party. Its leaders include former Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov, former Deputy Prime Minister Boris Nemtsov and former independent Duma Deputy Vladimir Ryzhkov.

Russia's secret services appear to have dealt Nemtsov a backhanded compliment this week, for his central role in organizing the rallies, by releasing hacked recordings of his cell phone conversations to the internet tabloid Lifenews.ru, which is co-owned by Yury Kovalchuk, a billionaire and close Putin ally. The private conversations, in which Nemtsov disparaged several fellow protest organizers in sometimes obscene language, appear to have been an attempt to divide opposition leaders.

Nemtsov says he has apologized and patched up his relations with his colleagues, but some damage might have been done.

"There is no doubt the Kremlin was behind this absolutely illegal breach of my privacy," he told GlobalPost. "Everyone can see the methods these people use. My goal, more urgent than ever, is to separate corrupted Putin from power and organize free and fair elections.

Navalny: the blogger-cum-folk hero

There are other potential leaders, who may benefit from not having a background in organized politics. They include blogger-cum-folk-hero Alexei Navalny, whose attacks on official corruption and fraud have migrated from the internet to the streets in recent weeks.

He is the author of the phrase "party of rogues and thieves," which public opinion polls suggest is the most widely-recognized and popularly-approved description ever expressed about Putin's United Russia party.

Navalny, released last week after a 15-day prison term for participating in an unsanctioned post-election protest, poured fuel on growing speculation that he might run for president if he's allowed to. Taking aim at Putin personally, he told cheering supporters that "the party of rogues and thieves is putting forward its chief rogue and its top thief to run for the presidency. We must vote against him, struggle against him."

Chirikova: businesswoman-environmentalist

Another organizer with genuine street cred is Yevgenia Chirikova, a former businesswoman who led an environmental group in the grim Moscow industrial suburb of Khimki in opposition to plans endorsed by Putin to build a toll road through a local old growth forest.

In several years of struggling, she and virtually all of her small band of followers were repeatedly arrested. One leading supporter was murdered; another was permanently disabled in an as-of-yet unsolved street attacks by thugs.

The battle for Khimki Forest propelled Chirikova to public attention, and then to the center of the current rallies against alleged electoral fraud.

"I don't make a distinction between politics and public activism," said Chirikova, in the kind of remark that tends to irritate some of her more politically sophisticated opposition colleagues.

"For me, real politics isn't something you study, it's done in the fields and the streets. Now we see lots of people coming into activity for the first time, and they're organizing themselves. That's the great thing about it."

On the left: a novelist and an agitator

On the left are potential leaders like novelist Eduard Limonov, head of the banned and heavily persecuted National Bolshevik party, whose personal style and ideology are cultivated in the image of Soviet founder Vladimir Lenin.

Another is charismatic street agitator Sergei Udaltsov, leader of a broad coalition called Left Front, who is considered so dangerous by Russian security forces that he was preemptively arrested on election day, allegedly for jaywalking, and has been held on a variety of pretexts ever since. Udaltsov declared a hunger strike, and was moved to a prison hospital where he was kept under constant guard by dozens of police and plainclothes officers of the Federal Security Service (FSB).

Reached on his cell phone earlier this week, Udaltsov said authorities fear him "as a person who can call upon people for decisive actions at a moment when public activity is on the rise."

But he added: "I have never broken the law, and never called for violence. The authorities imagine that I want to storm the Kremlin or something like that, but I just want to see the laws obeyed."

The nationalists

A less known quantity is Russia's shadowy nationalist movement, who were powerful enough to stage riots in downtown Moscow a year ago after one of their number was killed in a street fight with ethnic foes from Russia's southern Caucasus region, and police allegedly failed to investigate the death fully.

One nationalist street leader is Alexander Belov, co-chair of the Ethno-Political Movement, which surprised many by appearing with a large contingent at the Dec. 10 Moscow rally. Some experts say the little-known nationalists, who oppose "illegal immigration" by dark-skinned Caucasians and central Asians and resent the "dilution of traditional Russian values" in modern society, could be a wild card in any future political crisis.

"We represent a real political force, and our goals are shared by a large segment of the population," said Belov. "Not every member of our organization was willing to take part in that rally alongside other political forces, but more and more people understand that we have to act together. We demand that Putin resign. He should not be running for a third term. If authorities do not want to come to terms with the people, then we should take more radical steps."

The outlook

So far it's the liberals who speak for educated and relatively well-to-do urban protesters, who are ascendant.

But some experts warn that as the presidential election gets underway, and winter fades to spring, the segments of Russian society that are more attracted to the ideas of the left and the nationalists might swing into action.

Boris Kagarlitsky, a veteran left-wing activist and director of the independent Institute for Study of Globalization and Social Problems, says the middle class movement behind the Moscow rallies is unlikely to maintain momentum, because its leaders are too fractious and its demands too diffuse.

But it has opened a window for millions of people in Russia's far-flung hinterland for whom economic — rather than democratic — demands are primary.

"The real protests are yet to come," Kagarlitsky said.

"The vast majority of Russians, who saw their lives improve in the early Putin years, have experienced sharply worsening living standards since the economic crisis began in 2008.

Now the rally in Moscow has shown them that protesting is a possibility; it's a psychological breakthrough. We're looking at a classic revolutionary situation," in which a majority of people cannot go on living as before, the rulers cannot continue governing by past methods, and there is a precipitous rise in mass political activity, he adds.