North Koreans still defect, but their reasons are changing

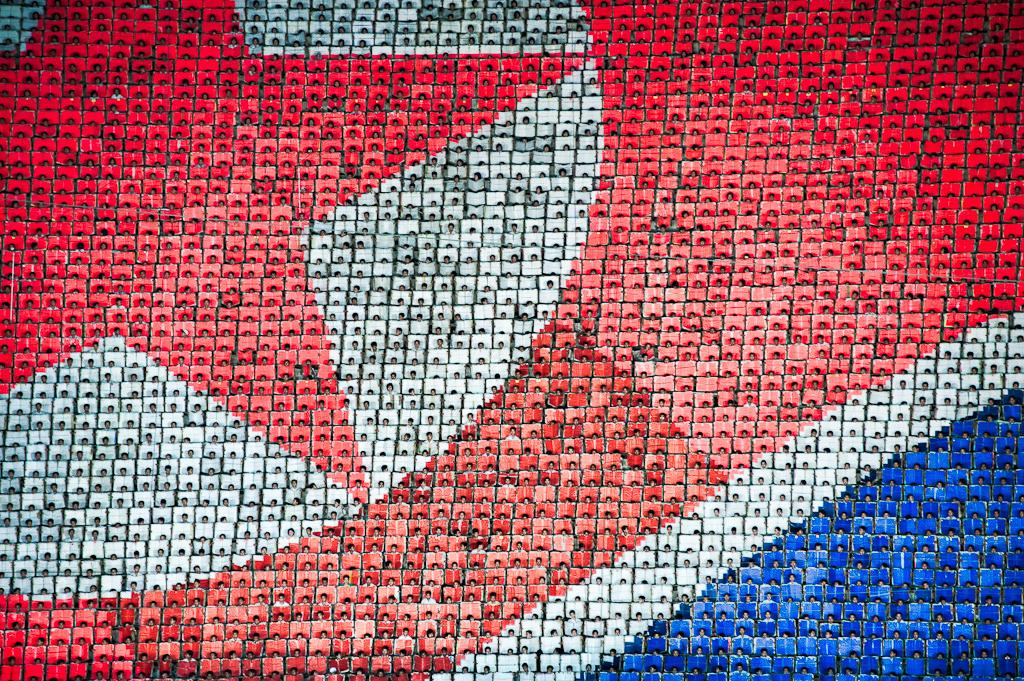

May Day Stadium, Pyongyang, North Korea. Sept. 9, 2011.

SEOUL, South Korea — There is just enough space in Ji Seong Ho's home for his textbooks, a few clothes and a mattress. He shares a bathroom and shower with neighbors, and his only kitchen gadget is a rice cooker.

Although his cramped accommodation in central Seoul is modest, it's still a world away from the life the 29-year-old led in North Korea until he fled in 2006 under cover of darkness.

Six months later, after a 6,000-mile journey that took him through China, Thailand, Laos and Taiwan, he completed the perilous trip that so many of his compatriots attempt, only to die en route or fall into the hands of unsympathetic Chinese authorities.

Yet more and more North Koreans are prepared to take such risks as they flee hunger and oppression in search of a new life in South Korea, where their newfound freedom is clouded by discrimination, mental health problems and financial hardship.

Video from GlobalPost: Will Kim Jong Un agree to nuclear talks?

At around 12 percent, the unemployment rate among defectors is far higher than the 3.4 percent among South Koreans. Those working earn significantly less than their southern counterparts, despite government subsidies and three months of mandatory resettlement training, according to the government-affiliated North Korean Refugees Foundation.

Even so, a recent government survey showed that seven out of 10 adult defectors are satisfied with life in the South; only 4.8 percent said they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied, according to the unification ministry poll.

About half of those questioned left the North due to food shortages, while 31 percent said they came to the South in search of freedom. Just over a quarter fled because of the North's political system.

They are among more than 23,000 North Koreans who have defected to the South since the Korean War ended in a truce — not a peace agreement — in 1953. The trickle of defectors through the 1990s rose dramatically about 10 years ago, the result of a prolonged famine in which more than 1 million people may have died.

Last year 2,737 people — one of the highest figures on record — defected to the South.

Seong Ho would almost certainly have died traversing the freezing Tumen River, which separates North Korea and northeast China, had it not been for his younger brother, Ji Cheol Ho.

The elder Ji had most of his left leg and his left hand amputated after being involved in a car accident as a teenager. Using a prosthetic limb provided by the South Korean health authorities, he now walks with a barely perceptible limp.

But he journeyed to freedom on a set of wooden crutches made by his father. "The river was really high because it had rained a lot," Seong Ho says of the night he and his brother, 26, bribed North Korean border guards with money sent back secretly by their mother, who had defected to the South in 2005.

"The current was strong, but we knew we risked being killed if we stopped where we were. Our only choice was to jump into the river. I had to swim with my good leg and my crutches. At one point I started to sink and thought I was about to die, but my brother helped me across to the other side."

The pair split up in China to avoid arousing suspicion, agreeing they would swallow the poison they were carrying if they were caught. Incredibly, with the help of brokers, religious groups and a large slice of luck, they survived the long journey over land and sea. When they next met they were in Seoul — free, in one piece, and reunited with their mother.

Their bid for freedom could easily have ended in China, where the authorities are taking an increasingly hard line against defectors. Last week, South Korea's parliament condemned the authorities in China after it emerged that they had forcibly repatriated more than 30 defectors captured along the border.

But their joy at arriving in Seoul was tempered by the discovery that their father had died after making an unsuccessful attempt to defect.

"He died a week before I managed to phone home," Seong Ho says. "He waited for us to contact him, but after months went without hearing from us he decided to try to cross the border. He was arrested and tortured, and asked repeatedly where his sons were. He died three days after his release. A neighbor found his body and held a funeral for him."

Every defector who arrives in South Korea brings with them a unique story of why and how they left the North. They are united, though, by a belief that life in the prosperous South will make up for the pain of separation from loved ones and the risks they took to get here.

Given those high expectations, it is inevitable, says Seong Ho, that some find themselves marginalized and disillusioned in their new home.

"We are a minority in South Korea, and that inevitably means there are challenges. North Korean students face discrimination, mostly because of their accent, so many defectors never get used to their new environment. It's all about having the determination to succeed," he says.

For his brother Cheol Ho, the simple pleasure of independent study is in stark contrast to the regimented life he led before. "Unless your family is part of the North Korean elite, you have to do an assigned job in a specific place your entire life, whether you like it or not," he says.

"But here in South Korea, you can do anything you like. You can study as much as you want, and you can dream beyond what you are capable of. You can even dream of becoming president. But that's not allowed in North Korea."

More from GlobalPost: Burma open for business?

The transition from the communist North to the capitalist South is hardest for the increasing number of young female defectors, many of whom are enticed by secret glimpses of life in the West on contraband videotapes.

"Most North Korean defectors I meet are women, and they have numerous problems," says Kim Yong Lan, a South Korean activist who helps defectors adjust to their new environment.

"They are very weak as a result of physical torture. They also suffer damage to their mental health, such as fear and anxiety. They have to go through hell to get to South Korea, but when they arrive there is no one here for them. They know there is a risk that the relatives they left behind will be tortured and forced to live without enough food. That makes them feel guilty about being here."

Kim Su Ryeon, a 23-year-old student, defected in 2006 with her mother, and arrived in the South two years later. "I once thought I had overcome my biggest challenge because I had defected and even experienced what it feels like to be on the verge of death," she says.

"So when I first came to South Korea I was young and thought I wouldn't be afraid of anything. … But I was wrong. I am now safe here, and my safety is important, but I now I face other psychological problems."

Do Myeong Hak, secretary general of North Korea Intellectuals Solidarity, a Seoul-based group of defectors, says the number of refugees will continue to rise, but not just as a result of famine.

"It's not just an issue of the food supply," says Do, a poet who arrived in South Korea five years ago. "Even people who can make a living in North Korea are deciding to defect because they are more aware of the outside world. More information is reaching North Koreans. Even if the food supply is maintained, the number of defectors will continue to rise."

The Ji brothers, now university students in Seoul, try to help other defectors through their organization Now, Action, Unity, Human Rights. While he builds bridges between young North and South Koreans through campaigns, meetings and social events, Seong Ho is making plans, a simple luxury he never thought possible six years ago.

"I'm a student and I don't have regular income, but once I get a job I should be able to make money," he says. "I live in a much smaller room compared to the one in North Korea, but I'm definitely happier here.

"The difference between South and North Korea is like the difference between heaven and hell."

More from GlobalPost: Next of Kim, an in-depth series

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!