Drug war ensnares big banks for letting Mexico cartels stash cash

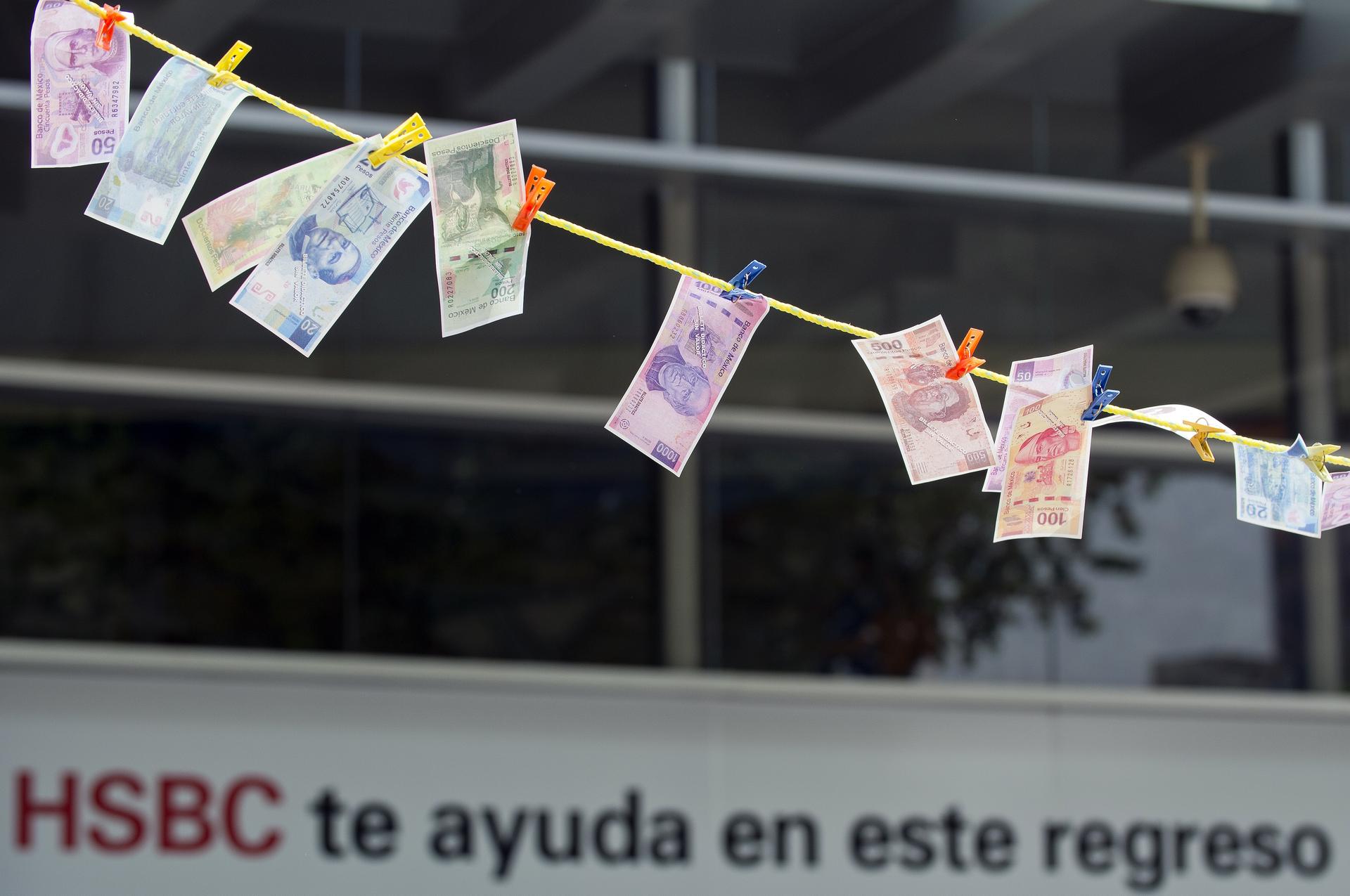

Fake notes were hung out to dry during a protest in front of HSBC in Mexico City on July 30. The bank was fined for failing to apply anti-money laundering rules.

MEXICO CITY — On the facade of the tall HSBC bank headquarters here, there’s a dark reflection of the Angel of Independence monument, one of the most iconic landmarks in this capital city.

The towering bank’s central location at the Plaza of Independence is a metaphor for its importance to Mexico’s financial system.

“It’s in the heart of the capital, in the most emblematic part of [the city],” said Myrna de los Santos, a finance professional who works in one of the neighboring glass office buildings. Looking up at HSBC Tower, she said, “This is the bank that’s been accused of laundering money.”

HSBC and other major banks have been accused of helping launder money for the narco criminals seen waging a brutal war in Mexico largely to win drug markets in the United States.

HSBC officials say they are cooperating with investigators. “What happened in Mexico and the US is shameful, it’s embarrassing, it’s very painful for all of us in the firm,” HSBC’s CEO Stuart Gulliver said in a July 30 conference call.

The accusations come as Mexican and US authorities have ramped up crackdowns on transnational crime rings’ vast earnings. Government prosecutors say they are chasing down drug profits and more aggressively targeting the financial institutions that let those profits amass in their vaults.

A US Senate investigation has accused HSBC of laundering $7 billion, transferring funds for Mexican clients through accounts in the Cayman Islands to accounts in the US.

More from GlobalPost: Venezuela nabs top Colombian drug lord

Bank of America allegedly opened and operated accounts for a US-based money laundering racket run by Los Zetas, Mexico’s most violent criminal organization. The Zetas allegedly used Bank of America accounts to buy $4 million worth of horses, and enter and win races, sometimes collecting nearly $1 million per victory, according to a New York Times report. (Bank of America has not been accused of wrongdoing and is reportedly cooperating with a US Federal Bureau of Investigation inquiry into the Zetas activities.)

HSBC, Citi, and Spain’s Banco Santander have all been accused of engaging in business transactions with Mexican money exchange houses that are suspected of money laundering.

HSBC is likely to be the first of these to reach a settlement with US authorities this year. On July 30, the bank announced it had set aside $700 million to cover the possible costs of a settlement of the money laundering investigation.

Duncan Wood, who researches and teaches about organized crime at Mexico City’s ITAM university, told GlobalPost the fact that a respected global bank such as HSBC has been pulled into a money laundering scandal in Mexico “shows that it’s not just a Mexico problem [but rather] an international problem.”

The recent investigations build on more than a decade of probes into the global flows of illicit cartel capital. One find, in 2006, was particularly emblematic of how drug trafficking routes and illicit money trails overlap.

In April of that year, Mexican soldiers searched a jet that had landed in a small airport 500 miles east of Mexico City. They found 128 black suitcases stuffed with nearly six tons of cocaine, a quantity with a street value of $100 million, Bloomberg reported. Later, investigators discovered the smugglers had used accounts at Bank of America and Wachovia to buy the plane.

Prosecutors in the US began digging deeper into Wachovia’s other dealings in Mexico. In 2007 securities regulators raided the bank’s headquarters in St. Louis. In 2010, the bank, now a subsidiary of Wells Fargo, agreed to a $160 million settlement with the US Justice Department.

The Wachovia investigation and fine — the largest money laundering settlement ever levied against a US bank — apparently did not serve as a deterrent. As drugs continued to cross into the US, criminal organizations continued to use major banks to transfer and launder their money.

Alejandro Hope, a security analyst and former researcher for Mexico's national intelligence agency, told GlobalPost that out of the estimated $65 billion US drug users pay annually for illegal drugs, “6 to 10 billion dollars per year” cross back into Mexico. Other researchers, such as President Bill Clinton’s former anti-drug czar Barry McCaffrey, claim that the annual figure for illicit funds moved back to Mexico could be much higher.

“There are a lot of diverse findings about the quantity of cash from contraband drug sales that annually crosses from the United States to Mexico, some of these estimates go as high as $40 billion,” Ramon Garcia Gibson, an anti-money laundering consultant in Mexico City, told GlobalPost.

Some of this money is stored in cash. For instance, when police raided alleged Chinese methamphetamine producer Zhenli Ye Gon’s Mexican mansion they found $208 million in paper bills.

More from GlobalPost: Mexico’s meth trade

Apart from copious cash piles, cartels reinvest profits in building up advanced arsenals and sophisticated trafficking methods, from cross-border smuggling tunnels to submarines. But they also send billions of their earnings back north to bank accounts in the US for safekeeping.

Mexico loses an estimated $50 billion per year — almost 5 percent of its gross domestic product — in illicit money outflows of different types, including money laundering, corruption and tax evasion, according to Global Financial Integrity, a nonprofit research and advocacy group in Washington, DC.

In 2007 and 2008, Mexicans used HSBC to process transactions which helped transfer a total of $7 billion to accounts in the United States, according to a report by nonprofit investigative journalism group ProPublica that analyzed a 355-page US Senate document on HSBC’s activities. The Senate’s investigation revealed that, between 2006 and 2009, the bank’s US arm did not engage in any money laundering monitoring regarding transactions with HSBC banks in other countries around the globe.

Now prosecutors on both sides of the border are cracking down on institutions that have served as conduits for massive cash flow with apparently little or no oversight.

On Jan. 22, 2010 a Mexican judge accused the owners of six money changers in Sinaloa and Tijuana, two cartel hotspots, of laundering drug funds through their accounts at the Mexican units of Banco Santander, Citigroup and HSBC. Then, on June 7, 2012, the US Treasury seized assets belonging to relatives of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, Mexico’s most powerful drug trafficker, a man Forbes estimates to be worth $1 billion.

Duncan Wood, of ITAM, explained that the anti-cartel strategy is simple. “Don’t go for the product, there’s always more product. Go for the money,” he said.

In June, the Mexican Finance Department announced it would cap the amount of cash dollar deposits banks can allow. Mexico’s congress is working to pass a new anti-money laundering bill that would place limits on trades in real estate, jewelry, and automobiles, transactions often used by criminals to hide illicit profits.

Hope, the security analyst, told GlobalPost that “the bill in congress could prove significant” by limiting criminals’ ability to make cash purchases.

In July, HSBC agreed to pay Mexico’s financial market regulator a fine of 379 million pesos ($28 million) for failures in detecting and reporting unusual transactions. The bank could now face hundreds of millions of dollars in money laundering fines and settlements in the US.

In the near future, drugs will continue to cross north into the US and money will be sent south into Mexico. The big banks, though, are likely to try harder to detect and prevent money laundering. HSBC in particular will need to burnish its reputation.

Looking up at the massive logo on Mexico City’s HSBC Tower, de los Santos, the finance professional, said, “they’re going to clean up their name and change their policies, but I wouldn’t put my money there.”