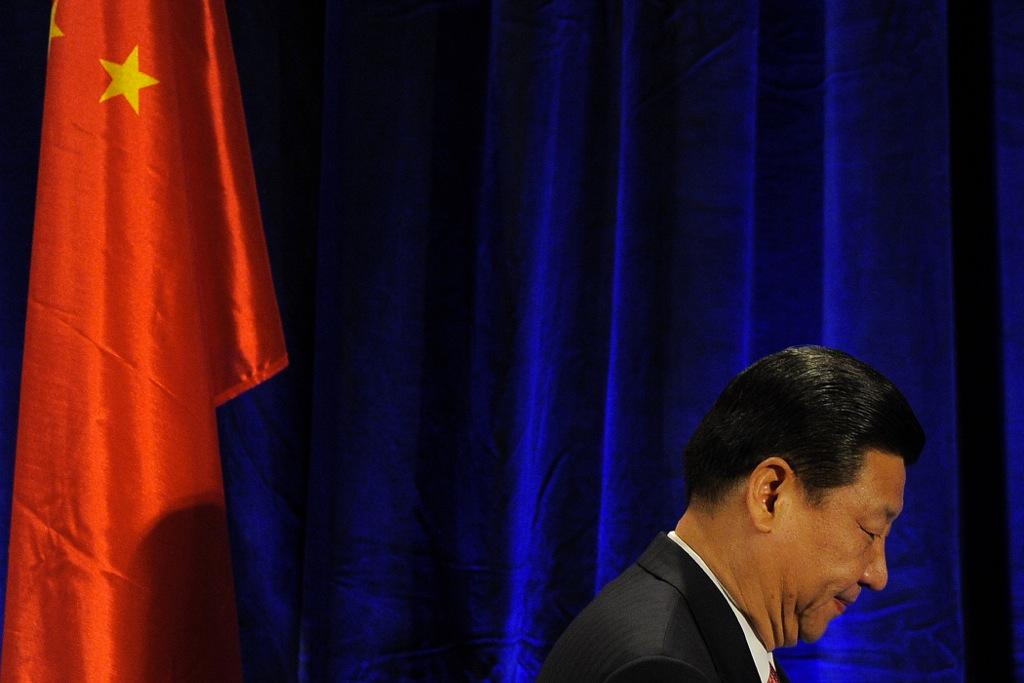

Xi Jinping’s first 100 days: still waiting for human rights progress

International pressure is mounting on President Xi Jinping to enact substantial economic reforms in China. His upcoming summit with US President Barack Obama could prove to be a turning point.

HONG KONG — Sacking high-level officials for corruption, slowing growth rates, seething tensions with Japan, a US summit at Sunnylands: Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first hundred days in office have not been dull. But do they offer any clues as to whether his tenure will be different from his predecessors'?

Before his formal assumption of China’s presidency on March 14, many hoped Xi Jinping and the new leadership would take bold steps to move China forward in areas where there has long been paralysis, especially on human rights and political reforms.

Xi’s early speeches reinforced these expectations: he portrayed himself as a reformer, promised a more responsive government, issued orders against lavish displays of wealth by officials and even launched prosecutions against some cadres for corruption.

Xi’s government hinted at reforms to notorious state systems, including the “hukou” residency registration, which discriminates against rural migrants, the petitioning system and the "re-education through labor (RTL)" system, which arbitrarily detains individuals for up to four years without trial. The downgrading of the power of the internal security chief also raised hopes the ballooning “stability maintenance” machinery that ensured the suppression of dissent might finally be curbed.

It’s probably unrealistic to expect Xi to turn around long-standing Chinese government practices within 100 days. But it is not unreasonable to hope that a new leadership serious about fundamental reforms would back off punishing individuals who are pressing the government to fulfill precisely those promises.

On March 31, two weeks after Xi became China’s president, four people were detained for unfurling banners in a Beijing public square calling on the government to implement a policy to require officials to publicly disclose their assets.

Since then, police have detained and arrested 11 more for allegedly participating in the same campaign. In early June—just a few months after the head of China’s Political and Legal Committee promised to “stop using RTL” by year’s end — Beijing filmmaker Du Bin was detained for “creating a disturbance” after he released a documentary on the use of gruesome torture in a RTL facility.

While Xi vowed in March to, “always listen to the voice of the people,” the Chinese government has not relaxed controls over freedom of expression or assembly.

In May, the party-state issued a directive to universities ordering them to steer clear of discussing a list of seven taboo subjects including “universal values,” such as human rights, and another one calling on these institutions to strengthen the “ideological education” of young lecturers, according to media reports.

In early June, the government rejected applications to protest the 24th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre, and harassed those who dared to make such requests. One Jiangsu activist, Gu Yimin, was arrested later in June for “inciting subversion” after filing such an application.

Even more chilling is the use of extra-legal measures and violence against activists even as President Xi promised to “uphold the Constitution and the rule of law.”

In May, a group of lawyers attempted to visit an unlawful “black jail” in Sichuan and were beaten by thugs. The police not only failed to protect them but also briefly detained the lawyers for “obstructing official business.

In April, when lawyer Cheng Hai inquired at a Dalian court seeking reasons for a sudden delay in the trial of his Falun Gong clients, he did not get an answer but was instead beaten by police officers.

The targeting of family members to punish individuals for their activism also runs directly counter to the spirit of the rule of law, as in the heavy 11-year prison term handed down in June to Liu Hui, brother-in-law of imprisoned Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, and the ongoing harassment of family members of exiled activist Chen Guangcheng.

It is not too late for Xi’s government to begin making meaningful changes. But if after another hundred days the list of activists and family members who are being persecuted is still growing, Xi’s rhetoric will not be credible.

Chinese people are still waiting for real progress, and a failure to deliver political and social reforms is likely to exacerbate the serious “civil unrest” that Xi has warned about.

Maya Wang is an Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch in Hong Kong.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!